The Dever stream runs clear as air and in its chalk-filtered reaches a brown trout hangs as if suspended above a gravel bed. I watch, transfixed, disturbed only by the bullet-train whirr of a passing kingfisher.

These chalk streams around the famous river Test in Hampshire are dangerous territory for a writer, an Arcadia that has long tempted men to imprudent poetics. The feathered feet of Evelyn Waugh’s questing vole are never far away.

Yet here I am, the morning heat lifting the early dew and from the willows along the bank caddis flies rising to flutter and prance in the buttery light. Some of them land on the water to be swept downstream, but the trout, dark-speckled in its lie, stays calm (or, as Keats put it: “Then in a wailful choir the small gnats mourn / Among the river sallows, borne aloft / Or sinking as the light wind lives or dies”).

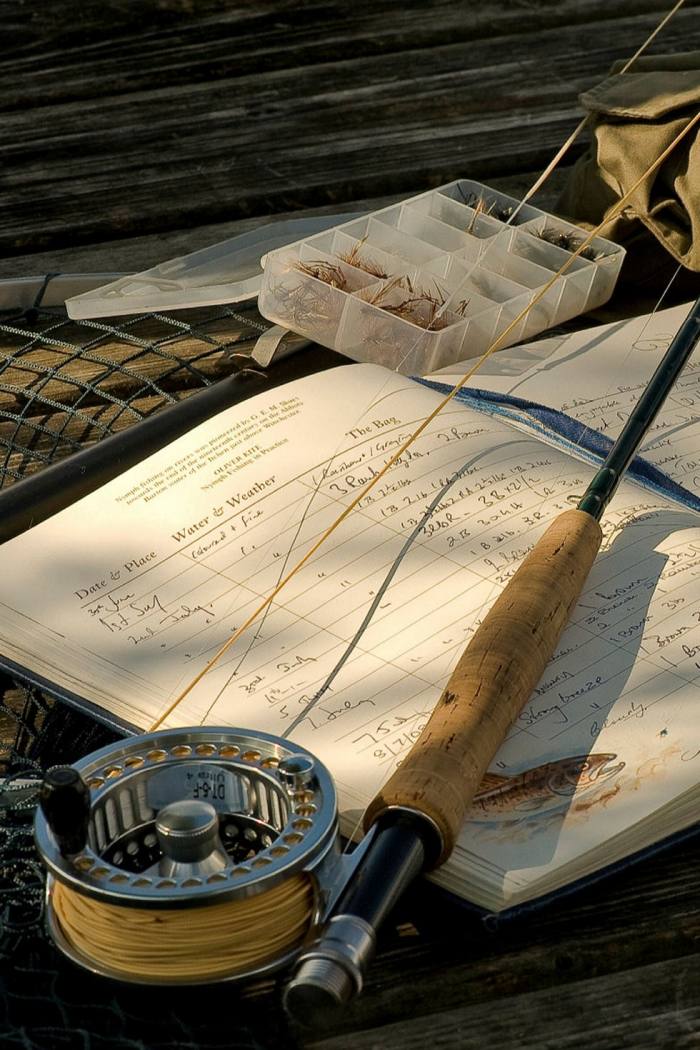

Rhapsody is a result of such streams providing a psychological ward for the troubled or just plain tired. Fly fishing requires concentration, knowledge, skill, various levels of exciting kit and, for the truly committed, an escape into the mind of a small fish.

Even the main river’s name, the Test, seems perfect, conjuring up that other great summer pursuit of the English gentleman, cricket. The two preoccupations are surprisingly similar. “It’s all about line and length,” as my pal Robert Sloss tells me.

Lately, though, fly fishing has broadened its reach. Role models such as Marina Gibson, April Vokey and Gilly Bate have encouraged in more women. Television shows such as Mortimer & Whitehouse: Gone Fishing, presented by two much-loved British comedians, have raised interest.

The Test is seen as the acme of the sport. But, in truth, that’s preposterous. The fish I am watching has been put in the stream by river managers tasked with keeping paying guests entertained. An unquiet American once described the river as the “longest stocked pond in the country” — which, trust me, is a very snotty thing to say.

But so what? The river, rising in Ashe near Basingstoke and flowing through a lattice of streams to Southampton water, is heartbreakingly beautiful and pleasant. Here, on the Dever tributary, the stream is no more than 10 feet wide, its gravel bed interspersed by water crowfoot weed that sways in the gentlest of currents. Pied wagtail dart through hawthorn, and pheasant’s eye and chamomile are readying themselves to bloom.

The trout rises to sip in a dun that is passing above it. I wait for the fish to settle and cast.

There are many reasons to fish — visceral, ephemeral, cerebral, it’s not quite as dull as golf — but the one that grips me increasingly is geographical. The sport takes me to places few others get to see: British Columbia, Patagonia or the Seychelles, but also the back-ways of the Home Counties.

So I find myself at London Waterloo, sitting furiously in Pret, waiting to board the 7.03 to Romsey. The cause of my mood is urban mundane: if I’d booked in advance the one hour, 28 minute trip would have been a tenner, but because I didn’t, it’s nearly £50. By the time I am passing the oddly romantic cranes of Southampton’s container port my spirits have lifted. Trees soon take over and I arrive.

A surprising number of perfect streams can be reached by train. I’m here because tour operator Fishing Breaks has launched a series of “Fly Fishing by Train” trips, to rivers a mile or less from a station and with accommodation in lovely English pubs nearby. They mean a blissful escape to the river can easily be appended to a business trip to London, say, or set amid a more conventional tour of the capital’s sights.

From Romsey station, it’s a 20-minute walk to the fishing, through the market town, past Boots, Bradbeers department store and, finally, the Cromwell Arms, where you can drop your bag.

For much of its length the Test is ribboned into channels that irrigate the valley, but I start at Broadlands Estate, where it masses in preparation for the sea. Broadlands is the home of the Earls Mountbatten, the house where both the Queen and Charles honeymooned, and Fishing Breaks has negotiated exclusive access to its water.

It feels very Brideshead, standing in the river in front of the house’s perfectly proportioned Georgian facade, lawn running down to the river’s edge. If anyone appears on the grass, I’ve been told it’s good manners to move downstream — but no one does.

The water here is dark enough not to offer up all its secrets. The grounds are full of cypress, oak and, in case I feel anxious to be so rapidly transplanted from the city, London plane. I’m looking for brown trout, which are finicky creatures (unlike finnock, which are boisterously Scottish). There are also rainbow trout, the eat-anything Labradors of the river, and out-of-season grayling, a gorgeous dragon-like fish whose presence shows the river is healthy.

Because the Test is wide here I’m wading in the stream. Your brown trout will ignore anything that doesn’t exactly replicate what’s fluttering about at that given moment. This leads anglers into a whole new obsession of its own, the effort to “match the hatch”.

You can go subsurface, mimicking a nymph clearing its riverbed pupa, although in certain parts this is considered déclassé. Or use an emerger, as if the fly is preparing to break through the water’s surface tension. Or you can pretend to be a fly that landed on the water surface and is now trapped. And this is all before you actually choose which fly.

So much to obsess over, so many boxes to look in. My friend Sloss spent years holding up flies to his young children and, with beady eye, demanding they name each one correctly. They seem not too badly damaged.

Luckily I have a guide, Malcolm Price, retired from IT to the riverbank. It’s very early in the season, but a hatch of caddis fly scatter over the river’s surface and small bulges form and then split in the surface tension as fish come up.

Malcolm hands me a sedge that mimics the flies floating down the seams in the water’s surface, and a brown trout takes. I’m quickly lost in nature, the only clock a circling red kite, its tail forked, hunting above me. It already feels a long way from London.

As dusk approaches, we walk back through the mature woods to the Cromwell Arms, a few hundred yards away. A classic coaching inn, it has a marquee ready in the garden for the stream of summer weekend weddings.

I check in. My view may be of the car park, but the bath is luxurious after a day in water. Then there is a friendly bar and a pint of Gale’s Spring Sprinter, as fruity as a butcher’s pun.

Simon Cooper joins me for dinner. Fishing Breaks’ owner is a former bookie who has written books on chalk streams, otters and the racehorse Frankel. He has been arranging fishing trips for 30 years from his home (and fly fishing school) at Nether Wallop, which by rights should make him a character in a Jilly Cooper novel.

Over plaice in the inn’s gentle dining room, he talks about the variety of fishing on offer, from fat stocked trout next to groomed lawns for the newcomer, to insanely difficult wild fish in thin overgrown rivulets.

He talks of the progression in the life of a fly fisherman. “First you want to catch a fish, then you want to catch lots of fish, then you want to catch big fish, and finally you want to catch that fish,” he says.

And he talks about dry-fly fishing and the Test. Fishing must be one of the oldest pastimes, and fly fishing — the art of casting tiny feathered lures using the weight of the line — goes back at least to the Romans.

But the art of the dry fly was developed on England’s southern chalk streams. FM Halford developed a new technique that let his fly float over the weeds that prosper here as summer takes hold — and then he held forth about it outside a hut on the Test at Houghton Mill. Now grateful anglers from all over come and leave flies on Halford’s grave, presumably causing a menace to feather-footed questing voles.

I had wanted to try a spot Simon rents on the upper Test called Whitchurch Fulling Mill, which can reached easily by train (the fishing an even prettier 20 minutes walk from Whitchurch station).

I’ve been told it is exquisite, clear and small, but in mid-April, despite the sunny days, it is still too early. Instead, the following morning, I’m picked up by Malcolm and taken to Bullington Manor, an estate about halfway between Winchester and Andover (and five miles from the station at Micheldever).

Bullington’s name evokes nascent prime ministers roaring through Oxford pubs, but it turns out to be pastoral perfection. Every fish for 20 yards can be seen in its place, noses facing the stream — which must be nice for the heron that flaps off on our arrival.

We start downstream at a small crossing called Venice Bridge and work back, casting upstream so that the flies drift back over the waiting trout. With a faint breeze in the reeds and the chirrup of songbirds from the bushes, the day passes in meditation. With very few flies hatching, I am often ignored, the fish darting away as we pass.

But then I spot that beautiful brown trout, fat and happy over its gravel bed. As Simon told me, sometimes a whole day comes down to one fish, however many others you might catch. It’s a long and tricky cast. Trees and bushes wait all around to snag the line, branches even hang over the surface.

But the fly lands well. It drifts down among the bubbles in the water’s seam and I watch the trout rise elegantly to greet it. I lift the rod and the fish is on.

Walking back, we meet the anglers fishing the neighbouring stretch. Astonishingly, they turn out to be Bob Mortimer and Paul Whitehouse. Bob smiles and asks if I’m any good, and then nods towards Paul, saying: “He’s very good.”

We chat about the fishing, and fishing generally. I note there are no TV cameras to be seen. It turns out they’ve gone fishing to escape the rigours of Gone Fishing.

Details

Ruaridh Nicoll was a guest of Fishing Breaks (fishingbreaks.co.uk); two days fishing at Broadlands and Bullington Manor, plus two nights at the Cromwell Arms costs from £490 per person (based on two sharing a room). A guide costs a further £345 per day, which includes use of all rods, reels and flies

Follow @ftweekend on Twitter to find out about our latest stories first

Credit: Source link