In 2008, the Erie Times-News assigned a then-staff writer named Cody Switzer and staff photographer Jack Hanrahan to an expansive summer project: Explore French Creek, from its source in Chautauqua County, New York, to its confluence with the Allegheny River in Franklin, Venango County, and report on what you see.

What that really meant was, tell most of us what we don’t see and don’t know about French Creek, one of the most biologically vital waterways in the United States, and its watershed. Chase its history. Its uses. Its health. Its place in the string of communities it links.

Switzer and Hanrahan put in and took out a canoe at access points all along the creek that summer, and over the course of five weeks in September and October published a series of features that captured the essence and importance of French Creek.

Their work resonated in 2008, and it holds up for posterity. It’s not a time-stamp but an imprint, a still life of an ever-moving subject that, in ways great and minuscule, makes us in northwestern Pennsylvania and southern New York who we are.

But the years between original publication and now are like dog years when it comes to technology. With every new iteration of www.GoErie.com since 2008, and the creative opportunities those advances bring to publishing, we often lost work built on an outdated platform or that fell between the cracks during migrations. The French Creek project was among those losses. We republish it here for the first time in years, in its entirety rather than in serial form. We’ve augmented the aggregated articles with newer videos, pictures and links to related articles that provide updates or additional information.

Jack Hanrahan today continues to create award-winning pictures and videos for Times-News readers and now for the USA Today Network. Cody Switzer in 2021 is a content specialist with Salesforce.com. When we left them in 2008, it was with an opinion column by Switzer at the conclusion of the project that had published every Saturday for five weeks. That column is where this republication starts, the better to set the stage for the journey that follows, and that French Creek and other wild places still invite us to take today.

— Matt Martin, executive editor

Erie-area nature spots taken for granted

If you spend enough time talking to people about wild bodies of water in our region, you’ll run into one cliche over and over.

“When you are here, you could be anywhere,” people say.

Then they compare the lagoons in Presque Isle State Park to the Everglades or some exotic place in Africa. Others compare fishing on French Creek to casting a line in Montana or Canada.

It’s partially true.

I’ve been fortunate enough to canoe both the lagoons and French Creek. I can attest to the fact that both places conjure up thoughts of far away and exotic locales.

You could look around the lagoons and feel totally isolated from society, even when only a mile from the city. You could spend three days canoeing French Creek and see two other people on the water. These are actual wild places, so we reach for travel-brochure analogies and pick locations from the popular imagination.

I think it mostly stems from the fact that we really can’t believe these places are in our own backyards because we are so detached from what the land here really looks like.

And so the problem with comparing these places to faraway destinations is that it takes a little something away from our own region and builds the idea that those are the only places that wild country still exists. We never really appreciate what we have for what it is.

It’s easy to take something like French Creek for granted when you drive over it every day and never get down into the water, never take a close-up look at what we have here.

I’m just as guilty of this as anyone.

I lived in Meadville for two years without coming anywhere close to French Creek. Then I spent a summer with the French Creek Watershed Research Program — splashing around the watershed taking bedrock measurements and doing water tests — and I couldn’t believe what was there. I ran across a small, untouched waterfall on a tributary of French Creek and was completely surprised.

I took this recent story series and was sent back out on the water, and gained a deeper appreciation of the place and a broader understanding of what it should mean to us, how it flows through our environment, economics and basic quality of life.

I think it’s something that more of us should do.

So here’s my challenge to you — get out onto a body of water like French Creek. Canoe over it, walk through it and explore it. You will find something that you can’t believe is here.

But then, before you compare the creek to some far-off destination, stop and think.

Hopefully you’ll decide, like I have, that there’s really nowhere like that stream.

Cody Switzer was a staff writer at the Erie Times-News from 2007 to 2009.

Community treasure: Where French Creek starts, so does history

SHERMAN, N.Y. — Say you spill a drop of water on this overgrown logging road.

Imagine it doesn’t soak into the soil.

Instead, it runs into the shaded valley below, through the blackberry bushes and goldenrod and past the boulders dumped here by the last Ice Age.

It splashes into the shallow, muddy pond at the bottom of the hill and meets a stream flowing over four beaver dams and past nearby farmhouses, the village of Sherman, and south to Waterford — where a young Maj. George Washington delivered an ultimatum to the French in 1753.

The stream filters through freshwater mussels, sweeps past factories and farms near Meadville and Franklin, and meets the Allegheny River, then the Ohio River, the Mississippi River and the Gulf of Mexico.

But it would start here at the farthest point upstream — the last scribble of blue that still bears the name “French Creek” on maps.

Biologists devote their professional lives to this creek’s study. It’s nationally known to be one of the last havens for some rare species of fish and mussels. This stream is a glimpse at what the Allegheny and Ohio rivers would have looked like 300 years ago, before they became “working rivers” — dammed, locked and redirected to accommodate barges and industry.

Is it any wonder a sign proclaiming the creek “A Community Treasure” has been tacked up on almost every bridge that crosses the creek in Crawford County?

Here, though, it’s just a pool dammed by beavers and marked by some felled trees and an old rusting teapot.

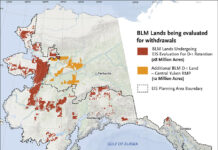

Article continues below map.

A dam, of sorts, shaped the stream as it is today.

It’s thought that the creek originally fed north into Lake Erie, and not south into the Allegheny River.

Many believe the stream’s flow was pushed south by massive glaciers that slid south from the Arctic into what’s now the United States between 115,000 and 7,000 years ago. That is likely, not certain, said Rachel O’Brien, Ph.D., associate professor of geology at Allegheny College and director of the French Creek Watershed Research Program.

O’Brien explained that a glacier could have easily redirected the stream, stopping the flow of water against the southern edge of the ice.

“You can think of the continental ice sheet acting as a dam against water movement,” she said. “It’s essentially blocking north-flowing streams, so at that point the streams are kind of dammed up and redirected.”

It’s not known where the ancient stream flowed. The glacier — which was about 2 miles thick in some places — would have covered the entirety of the creek and left behind soil and stones like the moss-slick boulders near the beaver pond as it retreated.

The village of Sherman, where the creek makes its turn to the southwest, had its own dam once.

It’s still marked on topographic maps — a black line holding back a pool of blue ink on the east side of Franklin Street.

Paul Sears’ father grew up in Sherman, spending his days in the pond behind the dam. He said his father used to tell stories about running to the pond, throwing off his clothes as he went.

Sears, who moved to his dad’s hometown about 30 years ago to become the preacher at First Baptist Church, said he used to fish on the pond, too. Now, he said, he misses it.

“It’s kind of sad because here in Sherman, a lot of the headwaters gather,” he said.

Locals said one night in 1979, the rains in the headwaters gathered and moved down the stream too quickly, breaking the dam and flooding the alley and basements along the south side of the main street in town.

The dam was never rebuilt.

The stream finds its own way.

French Creek’s tendency to wander forces Mike Meredith to move his fence once a year.

The stream meanders through his 180-acre, 40-cow dairy farm and flows about 30 yards from his home on Barcelona Road, about two miles downstream of Sherman.

Every winter, when the waters are high and fast and his pasture on the south side of Interstate 86 floods, the stream bank erodes just enough at this bend that he has to move his fence posts a few feet. It’s eroded so far back that a gas line running from a well in the field to a nearby house hangs over the water.

He’s done what he can to stop erosion there.

He installed the fence — with financial help from a conservation group — to keep the cows out of the stream. Their feet beat up the bank and only worsen the erosion.

“Their hooves are like little dozers,” he said.

Black willows are growing on the far side of the creek now. Meredith thinks the cows used to chew off the saplings. He’s hoping the trees grow and stabilize the banks. He knows he can’t control the creek, but he does what he can.

“It runs right down the middle of my farm, and I’ve learned to work with it and live with it,” he said.

People always have. ♦

Next: Traveling from Waterford to Cambridge Springs, we look at how French Creek brought settlers to the area and made George Washington a Colonial celebrity.

The French, the British, the Iroquois, George Washington and Waterford

WATERFORD — George Washington knew this meandering section of creek.

He paddled this same quiet stretch from Routes 6 and 19 near Waterford to Cambridge Springs.

Washington was here in December, though, on a dangerous trip that boosted his public status and only contributed to the building tensions between the French and English.

Washington, a 21-year-old major in the Virginia militia, took the assignment in October 1753 to carry a message from the governor of colonial Virginia through near-impassable wilderness to a remote French fort. He was the second man to attempt to deliver the ultimatum to the French, demanding they leave land that Great Britain claimed as its own.

It was one of the last diplomatic efforts before the French and Indian War, part of the worldwide Seven Years’ War.

As we paddle the same route Washington would have used when he left the French Fort sur la Rivière aux Boeufs — translated roughly to “Fort on the River of Beef” — in current-day Waterford, we wonder what from his journey could remain.

A green plastic turtle sandbox has washed into a clutch of fallen trees. A destroyed trailer home sits perched on a bank, its green toilet sitting sideways in a bathroom without walls. One of us carries two cell phones, both carefully wrapped in a plastic sandwich bag, in his pocket.

This section of stream is quiet and hidden, running mostly near forest and cornfields.

In places it seems so isolated that Washington himself might have seen the same sights.

When he traveled through the area, a mix of American Indian tribes, predominantly the Iroquois Confederation, would have lived near the creek, said Jonathan E. Helmreich, professor emeritus and college historian at Allegheny College.

The Iroquois, though dominant, were relatively new to the area, said Renata Wolynec, professor of anthropology at Edinboro University of Pennsylvania and director of the Fort LeBoeuf Museum. It’s believed that about 100 years before Washington’s journey, the Iroquois went to war with the Eriez tribe, effectively replacing the Eriez in the region — possibly because they were pushed west by the colonies, because of a grudge or for the resources of land and beaver pelts.

Today, this stretch of stream is lined with homes and cottages. The native towns of Cussewago and Venango became Meadville and Franklin, respectively.

European settlements were scarce at the time. Eventually, settlers were drawn to the region by descriptions printed in Washington’s popular journal of the trip.

“We passed over much good land since we left Venango, and through several extensive and very rich meadows, one of which, I believe, was nearly four miles in length, ” Washington wrote during his trip to the fort.

David Mead, founder of Meadville, read the journal and set out to claim the open land to eliminate much of the work of clearing and settling the frontier, Helmreich said. Meadville was founded in 1788, 35 years after Washington’s journey.

Much more land was cleared to create meadows and farm fields in the years that followed. Today, where there is forest, the banks are dotted with animal dens, carved into the mud between tree roots.

As we canoe through a wooded area near a rusting rail bridge, a muskrat swims along water’s edge, its brown head just above the water. Then, as suddenly as we spot it, it disappears into the mouth of one of the tunnels.

Muskrats like this — along with beavers and other fur-bearing animals — were part of the reason Washington was sent here on his errand.

The French claimed the entire Mississippi watershed, including the Ohio and Allegheny rivers and French Creek, Wolynec said. The plan was to pin the English colonies to the east of the Appalachian Mountains, control the fur trade and connect the French colonies in Canada with New Orleans.

River systems were crucial trade and communication routes in the wild, roadless country.

“Think about it not just as the frontier, but almost as an impenetrable wilderness, ” Wolynec said.

Fort sur la Rivière aux Boeufs was one of the first forts built to secure the path. It was completed in the summer of 1753, Wolynec said. Then came Washington in December, with a note telling the French that the governor of Virginia — and, by extension, the king of England — said they were trespassing.

The French commander obviously wasn’t pleased.

“He told me that the country belonged to them; that no Englishman had a right to trade upon those waters; and that he had orders to make every person prisoner who attempted it on the Ohio, or the waters of it, ” Washington wrote in his journal.

Washington’s journal of the trip was later widely published, partially to claim English ownership of the land, but also as a propaganda piece to support the war, historians say. People throughout London and the colonies read the journal when it was reprinted in newspapers, Wolynec said.

The journey elevated Washington to a colonial idol.

“It wasn’t he who published it, though he wrote it likely hoping that it would be published,” Helmreich said.

Washington would have been a true frontiersman to the journal’s London readers. They would read his description of an attempt on his life by a native, his dealings with the American Indians, his diplomatic efforts with the maligned French, and how the ice-clogged, wild creek made him weary.

“We had a tedious and very fatiguing passage down the creek, ” he wrote of their return trip down French Creek. “Several times we had like to have been staved against rocks; and many times were obliged all hands to get out and remain in the water half an hour or more.”

None of that is here now, on a near-perfect August afternoon on the stream — none of the danger and weariness.

The fur-bearing animals are much more rare, and so are the bears that Washington’s party hunted along the way. Native villages have been replaced with orderly creekside cornfields, split-level homes and manicured lawns.

There’s still a connection, though.

The same types of freshwater mussels Washington passed over still line the creek bed. You will still have to walk the canoe over the rocks. And, maybe most important, the creek still bears the name Washington gave it.

He was the first to call it French Creek. ♦

Here are some of the names French Creek has had, and their origins:

- In nungash: The Seneca chief Cornplanter once implied the supposed Seneca name for the creek referred to an “indecent” carving on a tree near the stream, according to “The Course of French Creek’s History,” a paper by Allegheny College historian and professor emeritus Jonathan E. Helmreich.

- Venango: One of the native names for the creek may have been derived from “Onenge,” the Seneca word for mink, or the Delaware term for the same animal, “Winingus,” Helmreich said. A tavern keeper in Wattsburg is also on record in 1845 as saying the word means “crooked.” Some believe the name could also be derived from “in nungash”

- Rivière aux Boeufs: The French name for the creek translates to “River of Beef” or “River of Cows.” Helmreich writes that the French named the stream after the wood bison they saw using the stream as a path, because the animals — which no longer live in the area — reminded them of cows. Renata Wolynec, professor of anthropology at Edinboro University of Pennsylvania and director of the Fort LeBoeuf Museum, dismissed the story, saying that there is no evidence the animals ever lived here.

- French Creek: This name was assigned to the stream by George Washington in his journals. Washington referred to the creek as “French Creek” because the town of Venango — now Franklin — was controlled by the French and flew the country’s flag, Helmreich said.

Next: We look at the animals of French Creek — the rare and strange, the majestic and graceful.

Among all French Creek’s creatures, mussels and hellbenders stand out

VENANGO — Gleaming half-moons dot the bed of the creek here.

Thousands of sparkling white shapes shine like cartoon smiles lying across the rocks.

The white and purple shapes are likely all you’ll see of the native freshwater mussels that call French Creek home. This is their last contribution to the creek at the end of their lives, some living as long as 100 years.

The living creatures are harder to find. Healthy and happy freshwater mussels lie mostly buried, looking like river rocks. You are almost guaranteed to walk across them without even noticing.

The nearly stationary creatures are found in French Creek in populations not heard of in other parts of the Ohio River system. This group of mussels has been untouched by the dredging and industry that destroyed their habitats downstream in the lower Allegheny and Ohio rivers.

Darren Crabtree, director of conservation science for the Nature Conservancy in Meadville, recently submitted a paper that estimates 15 million mussels live in French Creek. Some, like the northern riffleshell and the clubshell, are on the federal endangered species list, but hundreds of thousands of them can be found in the creek.

So of all the animals that live in and around the creek — the deer and beavers, the eagles and great blue herons, the rare fish and giant salamanders — the mussels are among the most important. The mussels are a sign of a healthy stream and a reason the stream is healthy.

2017: French Creek Valley Conservancy acquires more land

The first animals we see along the slow section of French Creek near the Conneauttee Creek access area weren’t native.

The cows lazily turn to inspect the commotion on the stream, chewing and bobbing their heads. One takes a short walk down the bank in an attempt to match the speed of our passing canoe.

Within a mile, the stream becomes more isolated, and the most common creekside critters are the great blue herons that pick through the shallows.

In all, 379 species of birds spend at least part of their year in the French Creek watershed — the term for all the land that drains into the stream — according to French Creek Conservancy President John Tautin’s fact sheet “Birds of the French Creek Watershed.”

The entire watershed contains four National Audubon Society Important Bird Areas, but none is along the creek itself, Tautin said. The areas — including the Erie National Wildlife Refuge and the Conneaut-Geneva Marsh — contain special habitats that support a wide range of birds like alder flycatchers and Blackburnian warblers, blue-headed vireos and ovenbirds.

There are still enough habitats and food for other birds along the creek. Floating downstream, you can see hawks and osprey gliding overhead searching for game.

Then, suddenly, a bald eagle glides gracefully through the creek valley.

Every rock we overturn on the creek bed sends a plume of silt into the water, lingering even in the quick riffles. When the sediment clears, a crayfish hidden in the cool, dark shadow sits still, maybe hoping not to be seen.

This part of the stream, with a bed covered in big, flat rocks, is a hotbed for the crayfish and one of its predators: the hellbender salamander.

The big, flat-headed salamander — which in French Creek can grow up to 2 feet long and weigh 5 pounds — is a sign of a healthy stream, said Cynthia Rebar, Ph.D., professor of biology and health services at Edinboro University of Pennsylvania.

Article continues after video.

Rebar brings students and the public to the creek. Her class once caught 10 of the protected salamanders in a day, she said.

“Everyone I’ve taken out — students and people from the community — they are just amazed, ” Rebar said. “They can’t believe that (the hellbenders) live here, and they didn’t know anything about them. They almost look prehistoric.”

The salamanders, once common in the Ohio River basin and Appalachian Mountain streams, are especially susceptible to runoff from heavy development because the extra sediment can cover their habitat.

If the habitat is preserved, however, hellbenders can grow large and move to the top of the creek’s food chain, said Jeff Humphries, a North Carolina-based wildlife diversity biologist who maintains the Web site hellbenders.org.

“They are kind of like the lions or tigers of stream ecosystems,” Humphries said.

More: Hell-bent for Hellbenders: ‘The canary in the coal mine’ of the Susquehanna River watershed

Mark Deka — who spent an afternoon fly-fishing near Saegertown — has seen hellbenders crawl by his feet in parts of the stream. He’s seen raccoons, muskrats and deer, too.

“You don’t really have to look for them. They just kind of show up, which adds to the fun of being out here,” Deka said.

Deka, of Cambridge Springs, started fly-fishing again five or six years ago. He usually comes to French Creek.

“It’s got everything you need — clean water, nice fishing, solitude,” Deka said. “People pay a lot of money to fish in streams like this.”

He caught two smallmouth bass out of a deep, shaded fishing hole in about a half-hour while talking about the stream.

The creek supports about 89 species of fish, not all as common as the smallmouth bass. There’s the eastern sand darter, endangered in Pennsylvania and threatened by agricultural runoff in many streams.

There’s the brightly patterned longear sunfish, also endangered in the state, which lives in rocky and sandy pools.

There’s the other, more common darters, bass, suckers, lamprey, introduced and native trout, perch and both native and harmfully invasive catfish, some easily visible from the seat of a passing canoe.

But for all the fish, there aren’t many anglers.

Deka said he’s only seen about 15 other people using the creek in his last six years fishing there. He said he can’t explain why more people aren’t drawn to the stream, but he doesn’t mind being alone.

“You can just kind of stand out here and be quiet for hours, ” he said.

One lone mussel — as wide as the span of a man’s hand — sits on the bed of the stream, the hinge of its shell pointing up.

It could have been on a journey, its white, fleshy foot dragging it blindly to a better spot in the stream, where it would dig into the bed and get back to feeding, siphoning creek water for particles. It will keep the good and the bad, eating what it can, and then deposit the harmful particles onto the creek bed.

Researchers believe that all the water in French Creek passes through a feeding mussel at least once, Crabtree said.

So the conservation efforts go hand in hand: preserve the creek to preserve the mussels, and preserve the mussels to preserve the creek.

2019: Invasive round gobies threaten Erie region’s French Creek mussel population

“We once thought that we had to save the creek in order to save all the rare creatures, and especially the mussels, that live there, ” Crabtree said. “Now, we are looking at saving the mussels or making sure the mussels are in good shape.”

Most of the responsibility to do both rests at the top of the food chain. Only people can prevent runoff and silt that choke out the eastern sand darter and the hellbender salamander and resist deepening and damming the stream.

So far, we’ve done a good job, but it seems that it’s been for no particular reason, Crabtree said. Our lack of serious development around the creek has been a bit of a “happy accident.”

We just have to keep it that way. ♦

Wildlife along French Creek

- Bird species: 379

- Fish species: 89

- Species of darters: 15, including the endangered eastern sand darter

- Freshwater mussel species: 27

- Hellbender salamanders once were found throughout the Mississippi River basin but now are limited to few locations. The salamanders can be found only in French Creek and parts of the Allegheny and Susquehanna rivers in Pennsylvania. “The vast populations now are in mostly the highest-elevation pristine streams. They seem to be the only (streams) that are protected by forests,” said Jeff Humphries, a North Carolina-based wildlife diversity biologist who maintains hellbenders.org.

- The Allegheny River contained about 40 different species of freshwater mussels in the early part of the 20th century but now has a much smaller population. French Creek has maintained a population of 27 different types of mussels, said Charles Bier, senior director of conservation science with the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

- French Creek’s healthy population of rare animals could be important to preservation projects in other parts of the country, especially for the federally endangered clubshell and northern riffleshell mussels. “Other states are now asking Pennsylvania if Pennsylvania would supply those species for restoration projects, ” Biers said.

Sources: Western Pennsylvania Conservancy, Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources, French Creek Conservancy, French Creek Project

Next: On to Meadville, where wilderness meets modernity.

At Meadville, wilderness runs alongside a modern town

MEADVILLE — The largest city along French Creek lies hidden somewhere beyond these wooded stream banks.

Yes, there are signs that the city and the stream have met — a tire and hubcap, concrete blocks and parts of a coffee pot on the streambed. Shopping carts coated in mud lie on the banks, while others strain leaves from the creek. A buried pipe trickles water into the stream, the rocks below stained orange with rust.

But the view of Meadville itself is mostly obscured by leaves and trees on the verge of fall. The more than 13,000 people living near the banks seem miles away, even though the town hugs the creek.

It’s not wholly surprising, considering that trees are much more common than towns here along French Creek.

The creek drains 686 square miles of deciduous, evergreen and mixed forests, about 55.6 percent of all the land cover in the watershed, while only 5.5 square miles (about 0.5 percent) of the area is dedicated to commercial and industrial business and transportation, according to the French Creek Watershed Research Program.

The lack of intensive development has been a kind of happy accident — the resources didn’t support mining, and the soil and the trees got in the way of factory farming.

Still, it doesn’t mean the stream is completely pure or protected forever from unchecked development and pollution, and it doesn’t mean people can stop thinking about how to keep French Creek the way it’s been for generations.

The places where runoff water flows into the stream are easy to find.

Muddy lines mark the steep banks where crops — mostly corn — are planted at the stream’s edge. These areas are where erosion is sometimes worst, because without trees, storm water can run almost unfettered into the creek.

In other places — like Meadville, where parking lots and roads keep water from soaking into the ground — storm water discharge into the stream can be more violent, said Charles Bier, senior director of conservation science with the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

The sudden rush of water carries dirt, chemicals and other pollution into the creek, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

The runoff also can disrupt the bottom of the stream and ruin habitats for creatures like mussels, Biers said.

This is a concern now in only a few places along French Creek, mostly parts of Meadville and other populated areas, so conservationists are taking steps to prevent it from becoming a serious problem

“If we get more and more of this (runoff) going on, more and more of French Creek will be impacted, ” Biers said. “It’s not just as clear-cut as not having more impervious surfaces, it’s also how that water is handled.”

Storm water runoff can become a particular problem in areas that develop quickly, so any sudden boom in growth in the watershed can be a problem, said Davitt Woodwell, vice president of the Pennsylvania Environmental Council, one of several organizations working to protect French Creek.

“It’s not an argument against development. It’s an argument for municipalities being ready for growth and knowing what they want to be,” Woodwell said. “There’s a lot of tools that the communities can chose from, and it’s just making sure they are ready for that when it comes.”

Great blue herons and fish can still be found near the banks of French Creek’s largest town.

Even before you pass the last of the shopping carts washed downstream, chances are you’ll see an osprey clutching a fish or an immature bald eagle.

It seems as if humanity has had little negative impact on animal life in the creek — then you read what Paul Swanson wrote in the September 1948 issue of American Midland Naturalist.

Swanson describes how he and his brother caught and sold more than 750 hellbenders from French Creek and its tributary, Big Sandy Creek, over 16 years. By 1948 — after hundreds of the salamanders were wrapped in damp moss and shipped — the hellbenders were scarce.

“This commercial collecting has apparently diminished their numbers considerably, as they are much more difficult to collect on that stretch of the stream at present, ” Paul Swanson wrote.

But the Swansons seem to be the minority in their exploitation of the creek, especially today.

“I doubt very much that there is a handful of business owners in the country that wake up in the morning and say, ‘How do I pollute something?'” said Jim Lang, vice president of Purchasing at Dad’s Pet Care.

Dad’s, one of the largest manufacturers along the creek, has made a concerted effort to protect the creek, said Lang, whose family founded the company. The company converted the property that once held Meadville’s sewage treatment plant into a place for their kennel and a field to catch storm water from the factory and parking lots.

Lang, himself, is a board member of the French Creek Conservancy and a longtime supporter of the French Creek Project, part of the Pennsylvania Environmental Council.

“They worked with people, ” Lang said. “In French Creek’s circumstance, it’s more about keeping it in good shape than needing to restore it. That concept fascinated the hell out of me.”

Farms are common along northern sections of the creek — corn grows to the banks and cows walk in the shallows — but here, between Meadville and Shaw’s Landing, it’s hard to find the fields through the trees.

Small farms still line the banks, but riparian buffers — trees and fields that slow erosion and runoff — shield most crops from view.

Alice Sjolander once worked with farmers to maintain the buffers and push other “best practices” to minimize farming’s environmental impact. The more she worked with farmers, she said, the more she realized how much they cared about the land and how willing they were to be environmentally friendly. If their land was sold and subdivided, new problems could arise.

“I said the best way to preserve our streams is to preserve our family farms, not as museums, but as working family farms, ” Sjolander said.

So to make small farms profitable, farmers began to produce “value-added products” such as organic meat and vegetables, glass-bottled milk and local cheese — products that could sell for higher prices because of how each was produced.

“We started to amass products, but where could the farmers be able to market these without (their goods) sitting on a shelf with 60 other products that are similar and lower quality?” said Sjolander, who is now market master at the Market House.

In 2005, the French Creek Project and the PEC took over management of the Meadville Market House with intentions to sell locally produced foods. In three years, food increased from about 10 percent of business to about 80 percent, Sjolander said.

Sales have also grown. In 2005, $50,000 passed through the market house. Now, about $160,000 changes hands each year, not including the farmers’ individual stands set up outside the building on weekends.

If you include that figure, sales could be as much as $500,000, Sjolander said.

The farms and forests along the creek just south of Meadville are replaced with manicured backyards and campground trailers as you near the Shaw’s Landing Access.

In one place, the grass is mowed to the stream, the steep bank eroded away everywhere except for where someone coated it in sloppy concrete, a few trees sticking out of gaps in the gray mass.

This is the kind of thing the French Creek Valley Conservancy is working to stop.

The conservancy works to preserve French Creek through natural easements around the stream, providing buffers from human impact.

The conservancy buys land and enters into protection agreements with landowners, said Conservancy President John Tautin. In most cases landowners give up development rights but receive a tax break, he said. The Conservancy owns 72 acres of land by itself, and another 191 acres it holds jointly with the Allegheny Valley Conservancy. The organizations also hold easements on another 677 acres, including 458 acres with the Allegheny Valley Conservancy.

Two other organizations — the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy and the Nature Conservancy — hold hundreds more acres in the watershed.

“The gratifying thing about this is that you get to work with a lot of people who love the environment and love their French Creek land and, in some cases, want to see them enjoyed by other people,” Tautin said.

That’s part of the mission, Tautin said, maintaining the stream for enjoyment.

So the next generations can enjoy French Creek and its feeders as Tautin did when he was a boy living on a dairy farm in the watershed, and as he still does now, living on a Cussewago Creek farm with his wife.

That’s the big picture for most conservationists — by reducing human impact on the stream, they work to preserve the stream’s impact on people. ♦

Next: We visit Franklin, where French Creek meets the Allegheny River.

End of the line: French Creek, the Allegheny River and Franklin, PA

FRANKLIN — Ten-year-old Alex Stephenson stood in the shallows of the Allegheny River, perched on two barely submerged rocks.

He looked at the creek bed and turned over a stone, waited for the silt to clear and examined the bottom for crayfish. Then he turned over another river rock.

His brother, 15-year-old David Foster Stephenson, stood on the bank. Their father, David Mark Stephenson, crouched downstream, picking through the shallows.

The boys had a day off school, so their dad brought them first to work with him at a construction site in Franklin, then here to a park on the Allegheny River, just downstream of where French Creek ends.

“You come to a city like Franklin here, and it’s beautiful with the rivers coming together, ” David Mark Stephenson said, standing on a stone in the stream.

Franklin was hardly visible from the park, with the exception of a few homes and backyards peeking through the wooded stream banks. Beyond the closest bridge was the low and grassy point where the creek meets the river.

For the Stephensons, who live in Akron, Ohio, this was a different kind of stream.

“We have the Cuyahoga River, which is pretty polluted, and the tributaries,” which are mostly storm runoff, David Mark Stephenson said.

He wanted to give his kids the same kind of experiences he and his six brothers and sisters had on vacations to Pennsylvania. Something about a wild stream makes people want to pass it on to the next generation — why else would so many teachers and people who love French Creek work actively to build appreciation of the stream?

So standing in the stream, where that appreciation seems to be built the most, David Mark Stephenson lifted a fat-headed tadpole out of the water and handed it to Alex.

Even the day after the remnants of a hurricane blew through the area, French Creek and the Allegheny River were still low.

But Ryan Wiegel said he has seen a swollen French Creek pour into the river after a storm. For a mile or so downstream, it’s like two rivers running next to each other, a clear division between the muddy water of French Creek and the clear water of the upper Allegheny.

But on this day there was none of that, just the same slow flow he’s seen most of the summer from the windows of his business, Wiegel on the Water, which sells canoes and kayaks out of a converted house and his father’s Wiegel Brothers Marine.

He’s seen the creek at its highest when he kayaks in the spring and fall, when the water runs over the grassy field behind his business. He’s also seen it at its coldest, paddling French Creek about twice a week in the dead of winter and gliding between ice floes on the Allegheny River.

“I guess I like the serenity, to get away from people,” he said. “A lot of people think it’s crazy.”

But what’s really crazy to Wiegel is how few people — even in this area — know how to enjoy waters he said can easily be used all year with the right equipment. He said there’s not enough awareness of French Creek or the stretch of the Allegheny River he knows so well.

No one has publicized this area, a place he sees as underused.

“It’s top-class water. It’s just not out there enough,” he said.

•••

The riffles where the waters from French Creek and the upper Allegheny River meet caught sunlight.

A great blue heron walked along the tall grasses.

Fish swam in place close to shore.

But traffic kept moving on the bridges that cross both streams. Two women argued in a sport utility vehicle, windows down and music way up, as they crossed the stream near Utica. People came and went and never looked at the water.

“I think that’s the way in most cities, with most waterways,” said Wendy Kedzierski, project coordinator for Creek Connections.

Creek Connections, a partnership between Allegheny College and schools as far away as western New York and Pittsburgh, educates children and teenagers about the importance of preserving French Creek and other waterways through camps and classes. The curriculum can be tailored to local streams but always focuses partly on French Creek, Kedzierski said.

“If they don’t see it and understand it, they aren’t going to appreciate it. Then, as adults, won’t work to keep it that way or improve it,” Kedzierski said.

Elliot Bartels, 15, said he’s gained that appreciation for the stream. Bartels, of Cranberry Township in Butler County, attended a Creek Camp on French Creek in July — hunting for hellbenders, taking water samples, canoeing — and took a yearlong Creek Connections course in his intermediate high school.

He’s worked on Connoquenessing Creek near his home, and has done water testing in Brush Creek, which runs through his backyard, but he said he’d never seen anything like French Creek.

“It just has a lot of animals that we don’t find,” Bartels said. “It has such a good water quality, it can support a wider variety of things.”

Judy Warren taught the Creek Connections curriculum to fourth- and fifth-graders for eight years at Sherman Central School in Sherman, New York. She used the stream to teach math, science and writing, and while the students learned all of that, she said she could also see an appreciation for the stream growing.

“You can just see the whole change in their demeanor about caring for the creek, ” she said.

•••

Say you spilled a drop of water at the headwaters near Sherman five weeks ago.

You chased it downstream, through farmland and forests, towns and wilds, and ended up here at the end of French Creek, standing in a grassy park with a view of the stream’s confluence with the Allegheny River, watching white clouds slide above the hills.

You can think of how the river formed or the mussel shells were dragged onto a log and ripped apart by some animal — probably a muskrat. You can consider the history of the place — George Washington’s miserable journey along the frontier creek in December or the seemingly infinite number of historical markers in Franklin alone.

You can reflect on humanity’s role shaping the creek and everything we are doing now to keep it the way it is.

But you might mostly think of a father and his sons turning over rocks in the shallows, classes of children looking for hellbender salamanders and how the stream flows through the lives of each generation, for better or worse. You might wonder what members of the next generation will see if they chase their own drops of water downstream.

So as you look out on the still-natural confluence— coming together between three wooded hills ready to burst into fall — maybe you’ll think of philosopher-conservationist Aldo Leopold.

“Perhaps our grandsons, having never seen a wild river, will never miss the chance to set a canoe in singing waters,” he wrote. “Glad I shall never be young without wild country to be young in.”

And maybe — looking out at the singing waters — you’ll understand what he meant. ♦

Float notes

Observations by Cody Switzer and Jack Hanrahan from some legs of the journey:

- Date of trip: Aug. 18, 2008

- Mode of transportation: By car and foot — the creek is too shallow to canoe.

- Distance traveled: About 8 miles.

- Weather: Sunny and clear, high of about 80 degrees

- The stream: Mostly shallow and rocky through wooded areas, shallow and muddy through farmland.

- Animals seen: White-tailed deer, kingfisher, cows, beaver tracks and dams.

- Highlight: Discovering the beaver pond at the origin of French Creek was a surprise. The valley was cool and quiet in the morning, with the sun filtering through the trees onto the water.

- Biggest mistake: Don’t wear shorts if you plan to visit the origin of French Creek. There’s high brush and enough berry bushes to cut up your legs.

- A word on cows: Cows are curious animals — very curious. As we waited for Mike Meredith to walk us into his pasture, the cows weren’t shy about examining us. Walking in, one of the cows ran up on photographer Jack Hanrahan from behind — he thought it was a bull and started running. Another licked my arm.

- Jack Hanrahan’s thoughts: The Village of Sherman Nature Trail is a great place to explore this time of year. A well-groomed trail parallels the creek as it meanders through meadows filled with goldenrod, grasshoppers and butterflies. We also saw a hummingbird. Finding the headwaters, where French Creek starts as a trickle, coming out of a series of beaver ponds, was tricky but worth the trouble. The area is heavily shaded, and a walk along the ponds will send groups of frogs jumping from shore to the shallow water. There are strange mushrooms growing around the bases of some of the trees. Cows should stay out of the stream, and my camera bag as well.

- Date of trip: Aug. 25, 2008

- Mode of transportation: Canoe

- Entry point: Route 6 & 19 Access Area– Latitude: 41°52’55.47″N– Longitude: 79°59’58.67″W

- Exit point: Cambridge Springs Access Area– Latitude: 41°48’24.89″N– Longitude: 80° 2’37.31″W

- Distance traveled: About 14 stream miles.

- Weather: Mostly sunny, high of about 70 degrees.

- The stream: Either low or slow. The stream in this section starts out shallow and rocky but transitions later to slow-moving sections of deep, muddy water. The entire length of the stream constantly meanders, and several trees have fallen into the stream.

- Animals seen: Muskrat, freshwater mussels, great blue heron, green heron, cedar waxwings.

- Highlight: We pulled the canoe up to a low, muddy shore so photographer Jack Hanrahan could shoot video of a butterfly. Along the narrow band of bare soil were tracks left by deer and raccoons, as well as the big, prehistoric-looking footprints of great blue herons. Of all the animals we saw on the creek, it almost meant more to see the tracks of the ones we didn’t.

- Biggest mistake: If you are going to paddle this section of the stream, bring a change of clothes and shoes. The water is low this time of year, and in a lot of places “canoeing” actually means walking in the stream with the canoe.

- Jack Hanrahan’s thoughts: We began our float below the bridge at Route 19 and 6N in Waterford Township. The creek is shallow in spots and requires dragging the canoe, but overall the creek has a gentle flow, which makes the paddling easy for several miles. The scenery is pleasant, a mix of dense canopy, open meadow areas and cornfields. We startled several blue herons, and we saw cedar waxwings above us for most of the float. Smallmouth bass and suckers darted from beneath the canoe. An osprey surprised us as we approached a bend in the creek. The last leg of the trip is a slog. The water is deep and slow. We paddled hard against a head wind to make it to Cambridge Springs. I have the blisters to prove it.

- Date of trip: Sept. 1, 2008

- Mode of transportation: Canoe and walking in shallow areas.

- Entry point: Conneauttee Creek Access Area Latitude: 41°48’39.74″ N Longitude: 80° 4’45.08″ W.

- Exit point: Saegertown Access Area Latitude: 41°42’31.34″ N Longitude: 80° 8’43.69″ W.

- Distance traveled: 10 stream miles.

- Weather: Sunny, high of about 80 degrees.

- The stream: The trip starts near the deep, muddy and slow-moving confluence of Conneauttee and French creeks. Soon, however, the stream becomes shallow and heavily riffled. It’s easy to spot fish and mussel shells underwater as you pass.

- Animals seen: White-tailed deer, bald eagle, osprey, red-tailed hawk, great blue heron, cows, various freshwater mussels, crayfish

- Highlight: It’s rare, even in our part of the state, to see a bald eagle flying wild. After a few false alarms — a red-tailed hawk, a faraway osprey — we finally see a bald eagle fly across the stream.

- Biggest letdown: Not finding a hellbender salamander along the creek. Part of the problem is likely our timetable — we have little extra time to stop and seriously look for them in the stream.

- Jack Hanrahan’s thoughts: We launch the canoe at a swampy access west of Cambridge Springs. The weather is perfect for a float, and it feels good to be rowing again. We stop at some riffles and hunt for crayfish. We paddle some more and come upon a shallow section of the creek covered with mussels. When you lift them out of the water, they close tightly, squirting water. We see our first bald eagle. It is a mature male, and the sun makes the white head and tail stand out as it flies downstream. We encounter a fly fisherman near Saegertown. This is the first person we have seen in two floats. He seems as surprised to see us as we are to see him. We stop to watch him catch a smallmouth bass. The creek gets pretty shallow as we get close to Saegertown, and we have to drag the canoe. It feels good to get out of the canoe and wade in the water.

- A note about protecting French Creek’s animal life: We write about a lot of rare — and very cool — creatures in this week’s article. While we have an abundance of these animals in our area, it’s best not to remove them from the stream. If you capture an animal from the creek, it’s best to let it go. Hellbenders, in particular, do not make good pets.

Credit: Source link