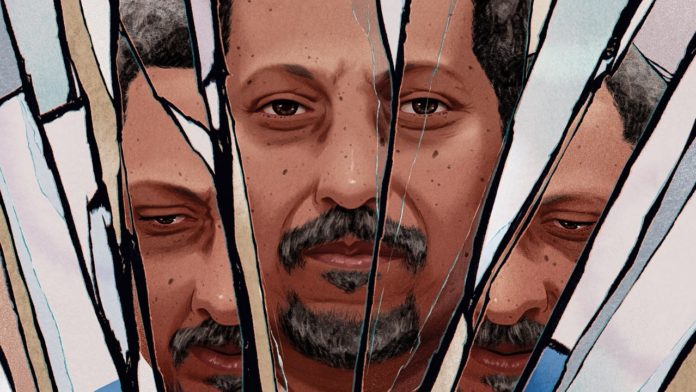

Percival Everett has one of the best poker faces in contemporary American literature. The author of twenty-two novels, he excels at the unblinking execution of extraordinary conceits. “If I can make you believe it, then it’s fair game,” he once said of his books, which range from elliptical thriller to genre-shattering farce; their narrators include a vengeful romance novelist (“The Water Cure”), a hyperliterate baby (“Glyph”), and a suicidal English professor risen from the dead (“American Desert”). Everett, sixty-four, is so consistently surprising that his agent once begged him to try repeating himself—advice he’s studiously ignored. “I’ve been called a Southern writer, a Western writer, an experimental writer, a mystery writer, and I find it all kind of silly,” he said earlier this year. “I write fiction.”

Beneath his work’s ever-changing surface lies an obsession with the instability of meaning, and with unpredictable shifts of identity. In his short story “The Appropriation of Cultures,” from 1996, a Black guitarist playing at a joint near the University of South Carolina is asked by a group of white fraternity brothers to sing “Dixie.” He obliges with a rendition so genuine that the secessionist anthem becomes his own, shaming the pranksters and eliciting an ovation. Later, he buys a used truck with a Confederate-flag decal, sparking a trend that turns the hateful symbol into an emblem of Black pride. The story ends with the flag’s removal from the state capitol: “There was no ceremony, no notice. One day, it was not there. Look away, look away, look away . . .”

Such commitment to the bit is exemplary of Everett’s fiction. Yet nothing he has written could be sufficient preparation for his latest book, “The Trees” (Graywolf), a murder mystery set in the town of Money, Mississippi. The novel begins, stealthily enough, as a mordant hillbilly comedy, Flannery O’Connor transposed to the age of QAnon. We are introduced to Wheat Bryant, an ex-trucker who lost his job in a viral drunk-driving incident; his faithless wife, Charlene; his cousin Junior Junior Milam; and his mother, Granny C, who zones out on a motorized shopping cart while the family bickers about hogs. The old woman appears to be having a stroke but is actually reflecting on “something I wished I hadn’t done. About the lie I told all them years back on that nigger boy”:

Granny C, it turns out, is a fictionalized Carolyn Bryant Donham, whose accusation that Emmett Till had whistled at and grabbed her, at the country store in Money where she worked, instigated the twentieth century’s most notorious lynching. On August 28, 1955, Donham’s husband, Roy Bryant, and her brother-in-law J. W. Milam kidnapped, tortured, and killed the fourteen-year-old boy for violating the color line. The case drew condemnation throughout the world but ended in Bryant and Milam’s acquittal by an all-white jury. (They later confessed to a reporter in exchange for three thousand dollars.) Donham, alleged by some witnesses to have participated in the abduction, went on to live in peaceful anonymity—until 2017, when, in an interview with the historian Timothy Tyson, she admitted to fabricating details of her encounter with Till. The octogenarian “felt tender sorrow” over Till’s fate but offered no apology. Her longevity renewed outrage about the half-century-old crime: Till died at fourteen; his accuser lived to finish her memoirs, which are due to be made public in 2036.

“The Trees” is not much interested in anyone’s tender sorrow. In the opening chapters, Wheat and Junior Junior—invented sons of Till’s killers—are found castrated, and with barbed wire around their necks. Beside each white victim lies a dead Black man in a suit, disfigured as Till was and clutching the white man’s severed testicles like a trophy. Later, Granny C is found dead of shock beside an identical besuited corpse. Similar murders occur elsewhere in the area, and, each time, a spectral body appears, stirring terrified rumors of a “walking dead Negro man.” The killings spread throughout the country; in several Western states, the vanishing corpse seems to be that of an Asian man. Is it the handiwork of a serial killer? A cadre of vigilante assassins? A swarm of vengeful ghosts?

Into this maelstrom Everett hurls three Black detectives: Ed Morgan, a gentle giant with a young family; Jim Davis, a wisecracking bachelor; and Herberta Hind, a misanthropic professional who joined the F.B.I. to spite her radical parents. (Jim and Ed work for the Mississippi Bureau of Investigation, often to their embarrassment: “That’s some crazy shit to yell out. MBI! Fucking ridiculous.”) Received with fear and prejudice by the town’s white citizens, the trio feels distinctly ambivalent about the case, which they initially treat as a dark joke. “Maybe it’s some kind of Black ninja,” Jim says. “Jamal Lee swinging lengths of barbed wire in Money, Mississippi.”

The detectives zero in on what seems like a conspiracy involving a soul-food restaurant (with a secret dojo) and a centenarian root doctor, Mama Z, who keeps records of every lynching in America. The stage is set for a Black-cop ex machina à la “In the Heat of the Night,” “BlacKkKlansman,” or the 2021 New York mayoral election. But the detectives quickly find themselves in the wrong genre of justice. What begins as a macabre sendup of the unreconstructed South culminates in a more unsettling and possibly supernatural wave of vengeance, as the killings assume the dimensions of an Old Testament plague:

The unresolved legacy of lynching might seem like a surprising choice of theme for the cool, analytic, and resolutely idiosyncratic Percival Everett. Brought up in a family of doctors and dentists, in Columbia, South Carolina, he studied the philosophy of language in graduate school, drifting from the dissection of invented dialogue into full-blown fiction organically. He wrote his début novel, “Suder” (1983)—the story of a baseball player’s madcap odyssey after a humiliating slump—as a master’s student in creative writing at Brown, where he met the great literary trickster Robert Coover. Everett, too, established himself as an author of terse and wily postmodern fiction, drawing on such influences as Lewis Carroll, Chester Himes, Zora Neale Hurston, and, especially, Laurence Sterne, whose “Tristram Shandy” remains a model for his playfully withholding work.

A character named Percival Everett makes opaque cameos in several of his novels but offers few keys to his creator’s life. Publicity-avoidant—he told audiences on his one book tour, for his twelfth novel, “Erasure” (2001), that he was there only because he needed money for a new roof—Everett likes to downplay his literary vocation. He routinely describes fiction as a sideline to hands-on pursuits like fly-fishing, wood carving, ranching, and training animals, especially horses, whom he credits with teaching him to write. Everett himself teaches English at the University of Southern California, in Los Angeles, where he lives with his wife, Danzy Senna, a novelist and a fellow U.S.C. faculty member. Yet he’s reluctant to admit that he has anything to teach. He speaks of writing fiction as a Zen-like process of unlearning, each novel leaving him more aware of his ignorance than the last. As he once said, “My goal is to know nothing, and my friends tell me I’m well on my way.”

Credit: Source link