Their illnesses were largely preventable. And yet, here they are.

“They just keep coming,” Mover said. “Unvaccinated patients just keep coming in.”

As the pandemic stretches on and cases climb again, a depleted battalion of health care workers is battling yet another big surge of COVID. Despite the widespread availability of vaccines, hospitalizations have approached last winter’s levels. And for many health care workers on the front lines still fighting COVID, hope has evaporated.

Since March 2020, the weary staff in this Mass. General unit have not gone a single day without treating a critically ill COVID patient. It is difficult for them to see a way out of the throes of this pandemic.

“I don’t see the light at the end of the tunnel,” Mover said. “This could be our new normal, which is not OK. Health care will not be OK.”

Even before the current surge, hospitals across the state were busy, crowded, and running low on beds. They are treating patients with all kinds of problems — cancer, heart disease, joint pain — including people whose routine medical care was delayed earlier in the pandemic. Amid this crushing demand from patients, hospitals are running short-staffed.

As Mover spoke to the Globe one recent afternoon, more than 100 COVID patients were hospitalized at Mass. General — nearly one-third of them in intensive care. Statewide, there were more than 1,900 hospitalized COVID patients, 65 percent of them unvaccinated. Among the most seriously ill patients, the unvaccinated share is even higher.

Mass. General treats many of the sickest patients in the state, and of those, the most critical are admitted to the medical intensive care unit known as Blake 7. It’s mostly quiet here, except for beeping alarms. Visitors are limited. The staff are in motion, but they don’t rush; their work, from donning personal protective equipment to moving a patient with a breathing tube, requires precision.

Many of their COVID patients need ventilators and heart-and-lung machines. They are sedated, unable to move or speak or see.

Some will spend weeks in treatment. Some will never recover.

Some patients regret not being vaccinated, and they ask for a shot before leaving the hospital. Others don’t believe they have COVID, even when they are so sick.

“There are some who are in complete denial and think it’s fake,” said Dr. Benjamin Medoff, a pulmonary and critical care physician. “We’ve had a few who are abusive.”

“I don’t let them yell at me,” he said, “and if they’re being inappropriate, I point it out to them. But I try to remind them that we’re just here to help them, and we’re doing the best we can.”

It’s the job of health care workers to care for every patient, no matter what personal decisions might have contributed to their illness. But almost two years into the pandemic, they admit that compassion is more difficult to muster.

Medoff, for one, isn’t angry about treating people who don’t believe in COVID and don’t believe in vaccination. “I feel more sad for them,” he said.

When the coronavirus first emerged, health care workers rallied to fight their new, unknown enemy. There was fear, but also a kind of excitement about the immense challenge of solving a new problem, Medoff said. That novelty has turned to drudgery.

Even during periods when broader society moved toward normalcy, COVID never left this ICU. The last time numbers ticked down in the fall, Medoff had a sense of foreboding. Sure enough, within days, more COVID patients arrived.

“It’s almost like this cloud,” he said. “It’s just relentless, like a blister you can’t get rid of, and you just wonder when it’s going to be different.”

Like his colleagues, there have been days he didn’t want to drag himself into work. But he did. And there have been days he couldn’t wait to get home.

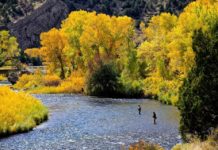

When he’s not working at the hospital, Medoff drives west to the Deerfield River and casts a line into the water. Fly fishing is restorative for him.

Mover, the nurse, clears her head while walking her three dogs or playing games with her two children, who are 9 and 11. When she gets home after a 12-hour shift in the ICU, she just wants to sit on the couch, watch TV, and go to bed.

Cassandra Batchelder, a respiratory therapist in the ICU, turns to “Brooklyn Nine-Nine” and other mindless TV shows during her time off. Nothing serious or heavy.

“I have no mental capacity for anything else,” she said. “It’s all used up here,” at work.

Batchelder monitors the many patients in the unit who can’t breathe on their own, and the equipment keeping them alive. Patients can decline rapidly; they may be chatty one day and intubated the next.

She can’t make sense of the fact that so many patients have refused vaccines, yet when they end up in the hospital, they want every treatment that modern medicine has to offer.

“It’s hard to be hopeful when there is a solution, and people are not receptive to the idea of getting the vaccine for themselves and for others,” Batchelder said. “I don’t know what’s left to get us through this.”

The best efforts of the ICU staff can’t save everyone. Patients die often — sometimes one a day, sometimes two or three. If their families can’t or don’t want to visit, nurses hold their hands at the end.

Some of them are young. The ones that stay in Mover’s mind are the pregnant women, and their babies, who didn’t make it. And the parents who died and left young children behind.

Mover recently took care of a patient whose children read books to her over the phone. The woman couldn’t hear them; she was sedated.

“You always think: What if that were me, and how would my kids handle that?” Mover said. “If I were to get sick, what would they do?”

Bearing witness to this suffering and death is emotionally draining. Some staff have left this work, forcing the hospital to rely more heavily on temporary workers, and to ask other fatigued staffers to pick up extra shifts.

But most of the staff, no matter how frustrated, keeps coming back.

What keeps them there? The camaraderie they’ve built doing their work together. And the uplifting moments, however few, when they bring a person back from the brink, when they remove the breathing tube of someone whose lungs are working again, when they hear the patient speak.

The ICU staff don’t see patients return to full health; when patients improve, they are moved out of the ICU and to a medical floor to make room for others who are sicker. But sometimes the staff receive notes and cards from patients whose lives they helped save.

“That’s what you hold on to,” Mover said. “You have to just keep thinking of those patients.”

Priyanka Dayal McCluskey can be reached at priyanka.mccluskey@globe.com. Follow her on Twitter @priyanka_dayal.

Credit: Source link