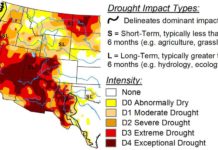

By October 2021, all of Montana was in severe drought — the worst the state had seen in decades. But Montana has seen bad dry spells before, forcing ranchers, farmers, conservationists and recreators to confront a collective dilemma: when water is in short supply, how can there be enough for everyone?

Transcript

Nick Mott Welcome to a Shared State. I’m Nick Mott. This season we’re hearing stories of Montanans navigating political friction. And today I’m here with reporter Shaylee Ragar. Shaylee, where are you taking us?

Shaylee Ragar I am taking you to a river valley in southwestern Montana. And I ended up here last summer, summer of 2021, when I was reporting on a historic drought that Montana and much of the West was experiencing.

Nick Mott I think I’m still a little scarred from last summer. I remember it well, like where I am. A lot of the rivers were closed to fishing part of the day because they were so low was so hot. I was just like sweating on my keyboard all day long. It was awful.

Shaylee Ragar Yeah, Nick, I describe it as having a bit of a personal existential crisis. All these news reports telling us how bad conditions were, telling us how scary conditions were. And the question that I kept asking people was ‘How do we prepare for this in the future?’ Scientists are telling us this is going to happen more often. Is there a good model to show us how we can be more prepared? And people kept telling me, ‘You need to go to the Big Hole Valley?’

Nick Mott Tell me more about the Big Hole.

Shaylee Ragar So it’s in southwestern Montana. The Big Hole River, which is 152 miles long of blue ribbon fishing. It runs through the Big Hole valley. Its headwaters is in the Beaverhead Mountains and it flows through to Twin Bridges. It’s pretty undeveloped, remains pretty pristine, and there’s still a lot of big ranches in the area. And I went to visit one specific rancher. His name’s Dean Peterson. He runs a cattle operation with his brother on about 6,000 acres.

Dean Peterson. This ranch sits 15 miles south of Wisdom, right between Wisdom and Jackson.

Shaylee Ragar I wanted to talk to Dean specifically because his family has been in this area for a very long time.

Dean Peterson. I’m a fourth generation rancher. Hopefully, my kids will be fifth.

Shaylee Ragar So Dean has three sons, and he wants his kids to take over his ranching operation like he did from his dad. Dean was there working with his dad on the ranch in the Big Hole Valley in 1988, which was the last time Montana experienced drought like it had in 2021.

Dean Peterson. And it was a really dry year, actually a little more moisture and we had this year, but the river went dry at Wisdom.

Nick Mott So the Big Hole is this big 150 mile river was dry there?

Shaylee Ragar Right. There was a section of the river by Wisdom that for about a month in 1988, was just a dry riverbed. And this was a really big deal.

Nick Mott That kind of drought, a river running dry seems like it’d be a huge deal anywhere it happened in Montana. But why was it a big deal in particular in the Big Hole?

Shaylee Ragar To begin with, the city of Butte takes about 40 percent of its city water from the Big Hole River. Then there are outfitters and anglers. You know they’re taking people fly fishing. Their entire business model is based on the Big Hole River flowing. And then there are a lot of ranchers in this area who’ve been here for a long time, who rely on the river to irrigate their land, to take care of their livestock and their crops. And like Dean Peterson described, water is essential to them.

Dean Peterson. The water is my lifeblood. That’s what keeps me on the land. That’s what keeps me raising cows. That’s what keeps me from selling the ground.

Shaylee Ragar The other reason I want to take you to the Big Hole is that since 1988, that really critical year, people there have been working to create a model to share the water. And I want to tell you the story about that.

Shaylee Ragar In this episode, we’re talking about sharing when there’s less to share. As climate change speeds up, can a model of shared sacrifice help us hold on to what resources we have left?

Nick Mott All right, Shaylee, take us back to 1988. What is going on?

Shaylee Ragar The way that Dean tells it, tensions in the valley really came to a head that year.

Dean Peterson. The biggest issue was the river was dry and the ranchers were using all the water. You know, the fish were dying because there’s no water in the river. And there are some conservationists in there that are saying, you know, you just this is wrong. You can’t do this to a river.

Nick Mott It sounds like these different parties like ranchers, fishermen and the eco system, which is not really a party, like all had to suddenly confront this things that they shared.

Shaylee Ragar And all of these different people have really different interests that are pulling them in opposite directions. And one of those key stakeholders that people might not think about is a fish in the river — Arctic grayling.

Nick Mott What about a grayling is so key?

Shaylee Ragar People who know a lot about Arctic grayling will tell you that they are not just any kind of fish.

Jim Olson They’re really cool fish.

Shaylee Ragar That’s Jim Olson. He’s a Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks biologist. Actually the biologist for the Big Hole River. And he says Arctic Grayling are one of his favorite types of fish.

Jim Olson The males, in particular, have a giant sail like dorsal fin that’s purple with spots on it. They have black slashes under their throat. There there are cool fish, very unique looking fish.

Shaylee Ragar The other thing about Arctic grayling is that they need cold rivers and lakes to survive, and that’s their breeding ground. And there are only two native populations of Arctic grayling in the lower 48, one in Michigan and one in Montana. But the population in Michigan went extinct in the 1930s, so Montana, the Big Hole River, is home to the lost native population of Arctic grayling in the lower 48.

Nick Mott I’m no biologist, but I would venture to guess that a river running dry would have a pretty big impact on a fragile native fish like that.

Shaylee Ragar Absolutely. And the federal government thought so, too. A few years after that big drought, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service was seriously considering protecting Arctic grayling under the Endangered Species Act to prevent them from going extinct. And that listing would mean that ranchers could be sued if their irrigation practices drained the river and hurt the fish. It would upend the way of life in the Big Hole.

Nick Mott It seems like it might have made people pretty mad.

Shaylee Ragar That is absolutely right. Have you ever heard the saying whiskey’s for drinking is for fighting?

Nick Mott That’s Mark Twain, right?

Shaylee Ragar That’s right. Yeah, and this is where that sentiment comes into play. We’re talking about the really complex system of water law in the western United States.

Michelle Bryan It’s a legally recognized right, typically attached to a piece of land.

Shaylee Ragar That’s Michelle Bryan. She’s a law professor at the University of Montana, and she literally just wrote the book on Montana’s water law.

Michelle Bryan It has characteristics that go along with it. It has an amount and it has a priority date.

Shaylee Ragar And that priority date means that water users with senior priority dates get to take a certain amount of water ahead of others.

Michelle Bryan Some years there may be enough water to fulfill all our water rights, but that might give a senior the ability to take all the available water in a lean water year.

Shaylee Ragar So that’s not like an equal system. If I had my water right before you did, then I get to use all I want, even if there’s not enough water for you.

Shaylee Ragar Right, exactly. It’s a system where water rights are over allocated. So it’s like selling more parking passes than parking spaces available, except people need water for their livelihoods and for survival. And the point I really want to drive home is that the river itself and the wildlife that depend on that river do not have their own water right. They’re not legally entitled to keep any of the water flowing through the river.

Nick Mott So it’s better to be a fourth generation rancher like Dean than a millionth generation toad when it comes to water rights.

Shaylee Ragar Yeah, I think that’s a good way to summarize it. One exception to that, though, is species listed under the Endangered Species Act. That listing makes it illegal to harm that species. So for grayling, it would mean some water needs to stay in the river in their habitat to keep them from going extinct.

Nick Mott All right, so let’s bring it back to the Big Hole. There’s this year of super intense drought than ranchers get the news that Arctic grayling may get federal protections. I have to imagine they’re not super happy about that.

Shaylee Ragar You know, they weren’t happy about that. They were really concerned about what that listing could mean. And landowners in the area started meeting informally, including Dean, the rancher we talked to earlier. His dad, Harold, was there

Dean Peterson. As dad would explain, it the first couple meetings it was close to blows.

Shaylee Ragar The way Dean describes it, it was a lot of kind of finger pointing at each other where anglers were saying ranchers were taking too much water. Ranchers were really protective of their livelihoods and their legal right to take water. And then conservationists were trying to speak for the fish themselves, saying they needed a healthy habitat. And so these are all differing interests. But then they realized they all wanted to avoid the same thing. They all wanted to keep Arctic grayling off the Endangered Species List.

Dean Peterson. And they come up with this idea that, you know, maybe we can all work together and find a solution for most of the problems.

Shaylee Ragar The solution they came up with was that they decided they needed to share sacrifice to protect the river. Dean says that it was a painstakingly slow process to figure out what that sacrifice would look like and that required ranchers, anglers and environmentalists to come together and form the Big Hole Watershed Committee.

Dean Peterson. What I told my dad originally when I got on the board and I said ‘the watershed committee, it’s just a slow move and nothing happens’ and he looks at me and he goes, ‘well, what were we talking about when you first started?’ and I told him. Ane he said, ‘OK, where are we on that?’ And then I realized at that point that, yeah, some of the stuff happens pretty quick. Some of it takes a lot longer. Some of it never happens. But in the end, it’s productive.

Shaylee Ragar Something that I think is really interesting, actually, is that Dean wasn’t originally part of this committee. His dad, Harold was and his dad got older, so Dean would give him a ride to these committee meetings, sat in the back and heard the kind of discussions they were having and decided he wanted to join.

Dean Peterson. But it does take time and it takes lots of talking and lots of working through issues and and it takes change. [00:10:47]I mean, especially nowadays you’ve got people on the left and people on the right, and there’s not much in the middle that’s happening. But that’s where all progress is made is in the middle, where you compromise. [9.3s]

Nick Mott So after all that meeting, what kind of compromises did they actually come up with?

Shaylee Ragar Well, there are several pieces to this puzzle of shared sacrifice. Outfitters and guides will give up fishing in the middle of the day when the temperatures are high and the flow of the river is low so that they don’t stress out the fish more. Ranchers and landowners will let the Big Hole Watershed Committee come onto their land and help them figure out ways to restore the watershed. So that could look like floodplain restoration or wetlands restoration. And then the big one is water rights holders signing agreements that say they will use less water than they’re entitled to to protect the river itself. And that has kind of a wonky name, it’s the Candidate Conservation Agreement with Assurances.

Nick Mott Wow, that is a wonky name. Let’s break that down a little bit. Like, why do ranchers agree to that and what do they get out of it?

Shaylee Ragar Yeah, I want to be clear that ranchers are not coerced or paid to sign these agreements. It’s definitely not mandatory. And this agreement, which is facilitated through the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, guarantees that water rights holders who use less water in a lean water year will be protected from legal liability if Arctic grayling are eventually listed under the Endangered Species Act.

Nick Mott So you mean they won’t get sued?

Shaylee Ragar Right. So the incentive here is that they won’t get sued, and Dean says that’s a good incentive. But he also says it’s just the quote unquote right thing to do,.

Dean Peterson It’s not good for me as a rancher to be greedy. You know, it’s mine I’m going to use it to work with you. That’s as a poor attitude. Very poor attitude, because it’s everybody’s resource. I don’t want to be the rotten apple in the box that ruins it for everybody else, you know.

Shaylee Ragar These agreements make the Big Hole Valley a very unique watershed in Montana. Some of these agreements have been in place since 1995, and we’re still in place during a historic drought year in 2021.

Nick Mott We’ll hear how the big holes model of collaborative conservation held up after a quick break.

We’re back with Shared State and Shaylee Ragar’s story about how anglers, irrigators and other water users in the Big Hole Valley made a plan in the 1990s to each use a little less water so the river wouldn’t run dry again. 30 years later how’s it working?

Shaylee Ragar Well, this model, where landowners voluntarily give up some of their water right is still in place and 34 members total have signed up in the Big Hole Valley, and they even gained a new landowner last summer. And while it is the single most important part of the Big Holes’ collaborative conservation, there is other work that the Big Hole Watershed Committee does to supplement those agreements, and that also helps keep water in the river. So I’m going to take you to a different part of the Big Hole Valley. Now we are going to Spokane Ranch with experts from Fish, Wildlife and Parks, the Department of Environmental Quality and U.S. Fish and Wildlife biologist Jim McGee.

Nick Mott What exactly is this project?

Shaylee Ragar It’s a floodplain restoration project. So there’s a stream that’s running through this ranch, a small tributary of the Big Hole River that isn’t functioning like it should. And so the land isn’t holding water like it should.

Jim McGee If it keeps going, it’ll dry it up. Basically, it’ll you’ll lose the whole green area. It’ll turn into drier species and won’t be nearly as productive.

Nick Mott So as you’re walking with Jim, tell me, what are you seeing? Like, what is this space?

Shaylee Ragar Well, first, I want you to visualize a really healthy stream. So let’s say it’s spring snow has melted feeding into this stream. Everything is green and looks really healthy.

Nick Mott So full on green, lush Montana’s spring. I got it.

Shaylee Ragar So that’s not what’s happening at this floodplain. I’m walking with Jim through a cow pasture and the cows are mooing at us. We’re tromping through a really crunchy sagebrush and the ground just really hard. And the way that Jim described it to me is that at some point, maybe even 100 years ago, a manmade structure manipulated the stream. So it could have been a culvert for an irrigation ditch. And that created a change in slope in the stream, forcing the water to run like a fire hose, meaning it leaves the watershed and is not stored there. But the elevation change doesn’t impact the entire length of the stream all at once, it slowly moves upstream. So when I went to this project site, we could see the spot where the slope changes. It looks like a little waterfall on the stream, and the stream morphs from a deep ravine where water is flowing like a fire hose to more of a swampy brook with level banks that is forming a healthy floodplain.

Shaylee Ragar You tell me what we’re looking at?

Dean Peterson This is the head cut, so that is the big spring complex up there. If we walk to see where those willows are, it’s that’s where it gets healthy. And so this is just degrading and moving up, and it’ll if it keeps going, I mean, it’ll take a long time, but it keeps going, it’ll dry it all out like this. So we want to we want to keep the water spread out and keep it green.

Nick Mott So how do you actually do that? How do you keep it green?

Shaylee Ragar Well, their idea is to use an excavator to reroute the stream around this manmade manipulation so that it hopefully returns back to its natural flow.

Nick Mott So kind of like a highway bypass or something, but for this little stream?

Shaylee Ragar Exactly, and it’ll be more manmade manipulation to correct original manmade manipulation. But the idea is that the stream will return to its natural function.

Nick Mott So why is the committee working on this? Like what’s their goal?

Shaylee Ragar The goal is to keep more water in the ecosystem, and you can do that by using less water or by holding onto it longer. And that’s what this project does. Pedro Marquez is chair of the Big Hole Watershed Committee, and he walked me through the project site.

Pedro Marquez This is what I was talking about. The whole thing is just a spongy. It’s like a little earth trampoline. So this is I mean, this is this is gold as far as the climate goes right.

Shaylee Ragar Now because it’s holding water?

Pedro Marquez Because it’s holding water. It’s it’s rich, it’s dark. That means there’s tons of organics nutrients, right. All the good stuff.

Shaylee Ragar So Pedro says the vision is a landscape like this where water is being held and stored and moving slowly through the watershed. And he says what’s really cool about this is that it’s a project that benefits both the rancher who is flood irrigating and needs to flood irrigate to make their operation work. And for conservationists who want better water conservation, it’s a win win scenario.

Pedro Marquez Like every little high alpine meadow that we can keep in its sort of maximum appreciate wetted sort of functioning hydrology, the better. It’s water in the soil and not on the surface flowing downhill as fast as it can, right? Because the soil is the best tool, we have to slow the movement of water out of the landscape.

Nick Mott So one project can help change how the water is behaving in this whole ecosystem.

Shaylee Ragar Well, Pedro says no, but it’s still really important.

Pedro Marquez Don’t have any illusions that, like the flows of the Big Hole river in August, will be noticeably impacted by us doing this work. But it’s like, 50 of these projects in this area. It’s like little, you know, a thousand thousand places of improvement is kind of the direction and it’s endless work.

Nick Mott So this work takes a long time. It’s expensive. At the same time, the climate is changing quickly and those impacts are being felt immediately on the ground. How does Pedro maintain that success is possible when you need the kind of scale he envisions?

Shaylee Ragar Do you remember how in 1988 there was a really bad drought and a section of the Big Hole River went dry? Well, we took a short drive to the section of river that went dry just outside of Wisdom, and he showed me why he feels optimistic.

Pedro Marquez There’s a picture of 1988 of this spot right here, bone dry with no vegetation on the banks, you know.

Shaylee Ragar So right. Know it’s pretty full?

Pedro Marquez This is base flow. This is like, this is sort of a natural kind of base flow condition here. And it’s I mean, it’s dramatically improved at this spot.

Shaylee Ragar There was less precipitation in 2021 in the Big Hole Valley than there was in 1988, in the same place. But the river didn’t go dry. And so Pedro says, we know collaborative conservation can work because the river is still flowing. And so far, Arctic grayling haven’t been added to the Endangered Species List. But like you said, it is expensive, it’s time consuming, it depends on grant funding and a lot of landowner buy in.

Nick Mott Right, and that buy in is another potential issue. None of this model is mandatory. You don’t have to do any of it if you don’t want to.

Shaylee Ragar Exactly. This model depends on human behavior. It depends on consensus. And so some people are asking if this model can continue to be successful as water becomes more scarce and people do a very human thing, which is to take what’s theirs. And there are people in the Big Hole Valley who sometimes don’t play ball.

Nick Mott What happens to this whole model of collaborative conservation when you have people who don’t play ball?

Shaylee Ragar It puts the whole model on shakier ground and makes it less likely that it’ll be successful. Participation can be pretty black and white in which some landowners sign the agreement and they give up some of their water, right? Some landowners don’t, and they insist on taking their full water right. But it can get more complicated and more convoluted than that.

Nick Mott How so?

Shaylee Ragar So you remember Dean, the rancher that we heard from at the beginning of this episode, he moderates his use of water, and at one point in time, his family’s ranch had a candidate conservation agreement to use less water when necessary. But when it came time to re-up that agreement, he didn’t want to. He said it would require him to sacrifice more than he thinks is fair.

Dean Peterson I guess we felt that we were already giving back a lot, to the stream, to the watershed, and they were asking us to do a lot more than we thought was comfortable.

Shaylee Ragar Dean is an example of why this is so difficult. He’s completely invested in collaborative conservation and water conservation, and yet still he’s not willing to sacrifice all that he’s been asked to sacrifice.

Nick Mott So even someone who’s really on board with the vision, with keeping more water in the river because it’s the right thing to do has limits about what they personally should do. If that’s the case, are there other models for how we can keep things from getting worse and worse as the West gets hotter and drier?

Shaylee Ragar Yeah, Nick, I asked the same question, and that’s when I came across Lee Nellis, who is a longtime land use planner who used to work in the greater Yellowstone ecosystem, and he now teaches at a college in New York. He actually wrote an article that I came across that said collaborative conservation absolutely has its limits because it isn’t enough to stand up to individualistic values that have been upheld in our legal system for as long as we can remember.

Lee Nellis When we get to decisions like that, where there is an intrinsic value versus a commodity value and there’s no open ground or at least precious little open ground, the collaborative approach just isn’t the right approach to that. You have to step up a scale, step up a level and say, OK, there has to be a broader social decision, political decision about what’s important here.

Nick Mott Can you give an example of what Lee means?

Shaylee Ragar Yeah. Lee says to look at how indigenous peoples managed the land we live on now, pre colonization.

Roslyn La Pier The Americas is a place where people have lived here for thousands of years. People have used this place for thousands of years.

Shaylee Ragar I spoke with Roslyn La Pier about this. She’s Blackfeet and Métis and a professor of environmental studies at the University of Montana. She says the biggest misconception is that Native Americans were simply hunters and gatherers and not land managers.

Roslyn La Pier It’s not just that people were kind of using the landscape as it existed. They were actually changing the landscape. They were changing it and a lot of different ways and managing it so that it was of benefit not only to them, but also to the natural world.

Shaylee Ragar A great example of this type of natural resource management is how the Blackfeet Tribe valued and protected beaver. So beavers provide a really important function in creating water storage with their dams in watersheds, and that was lost when colonizers commodified beavers for the fur trade. And to this day, there is a huge effort across North America to mimic that kind of work that beavers do naturally that we don’t see as often anymore.

Roslyn La Pier Indigenous people, for the most part, did not have to deal with things such as like starvation or want. In fact, they had the opposite, which is they had not only kind of the abundance of being able to take care of themselves, but they also were able to collect surplus.

Shaylee Ragar So it sounds like one of the ideas Roslyn is getting at is this notion of valuing the natural world for what it already offers.

Shaylee Ragar Right. Lee Nellis, that land use planner, says we’ve lost that intrinsic value. He says that as a society post colonization, we have commodified all of our natural resources and that until we change how we value those resources, collaborative conservation will just be a Band-Aid. And the evidence he uses is that the collective value system we have right now says we can run a river dry. So while that’s really philosophical, the the tangible translation here is how our value systems translate into laws and regulation. There are Montana’s lawmakers who have tried to create laws that require water to stay in rivers that say landowners can’t run rivers dry that give rivers their own water rights. And those proposals have always been dead on arrival because it would upend the system we have now.

Nick Mott Right to Lee’s calling for this big society wide shift that could create laws and policy and regulation. What if folks like Dean, you know, people who are using water on the ground think of ideas like that?

Shaylee Ragar Dean and other landowners in the Big Hole, really don’t think that regulation is a good idea. Dean says that people don’t like being told what to do, that it will change a system that they’ve operated under since manifest destiny brought people out to the West. And he says it’s it’s not even feasible to change the current system.

Shaylee Rager speaking with Dean Peterson I think in the minds of some people, a regulation to have an industry flow guarantees more water. But what I hear you’re saying is that isn’t the truth, that collaborative collaborations a better guarantee.

Dean Peterson Well, it’s a better route to take. I mean, if you have an instream flow, you’re guaranteed whatever that is. But if you’re talking the Big Hole River, where do you go get that? Where are you going to get? Are you going to get a little bit from everyone? How are you going to do this? You know, it’s just an added cost for everybody. More regulation and less cooperation. Everybody comes more greedy at that point, including me.

Shaylee Ragar I originally went to the Big Hole Valley because experts told me there is a model there that is very successful and the gold standard for water conservation. And what I found is a model that’s working in spite of the system it’s operating within. So the question from here is can other collaborative conservation models work, or will climate change push us to systemic change in the future? Montana’s will be updating its state drought management plan for the first time since 1995 over the next year, and I think that document is really going to show us how Montana’s plans to share this resource into the future.

Nick Mott Shared State is a podcast by Montana Free Press, Montana Public Radio and Yellowstone Public Radio. This episode was reported by Shaylee Ragar and edited by Nicky Ouellet. I’m your host, Nick Mott Mara Silvers produced this episode. Editorial Assistance by Corin Cates-Carney, Nadya Faulx and Brad Tyer. Fact checking by Jess Sheldahl and Gabe Sweeney is our sound designer.

Credit: Source link