Recalling the moment recently, Sandelin said he couldn’t remember if it was late in his high school days or in between one of those early years at North Dakota, but what he does recall is “some guy rolled in wearing sweatpants and a ball cap.”

“We didn’t know who he was until we got a closer look,” Sandelin, 56, said. “He had no gear. He asked if he could skate with us. We found him some gear. He was pretty good.

“Just watching him play the game was pretty amazing. He was wearing skates that were a size too big, he had none of his own gear, but still the best player on the rink.”

Described by one of his old coaches at UMD, Mike Sertich, as the original rink rat, Pavelich died on March 4 at the age of 63 while undergoing mental health treatment at a rehabilitation center in Sauk Centre, Minnesota.

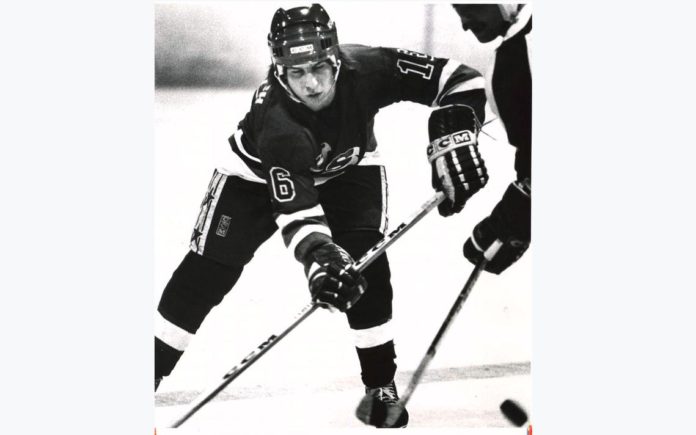

The Eveleth native played three seasons for the Bulldogs from 1976-79 and was an All-American in 1978-79. A member of the 1980 “Miracle on Ice” U.S. Olympic team, he also went on to play five seasons in the NHL with the New York Rangers.

The Bulldogs are sporting a No. 17 patch — Pavelich’s number at UMD — during their 2020-21 postseason run, adding the tribute to their uniform last week at the NCHC Frozen Faceoff in Grand Forks, North Dakota. UMD awaits its NCAA tournament fate, with the field of 16 being announced Sunday.

Sporting No. 17 patches in honor of former Bulldog Mark Pavelich, Minnesota Duluth forward Koby Bender celebrates his power play goal with fellow Bulldogs Matt Anderson (3) and Tanner Laderoute (13) in the second period of an NCHC Frozen Faceoff quarterfinal game on March 13, 2021, at Ralph Engelstad Arena in Gran Forks, North Dakota. Nick Nelson / File/ Grand Forks HeraldNick Nelson / Grand Forks Herald

Sertich, head coach at UMD from 1982-2000, was an assistant coach for the Bulldogs during Pavelich’s playing days at UMD and he wasn’t surprised to hear Sandelin’s story. It was a familiar one for anyone who grew up on the Iron Range.

A Virginia native, Sertich recalled a story from when Pavelich was back home while on a break from playing with the Rangers. Looking to get some ice time but not wanting to attract any attention to himself, the NHLer and Olympic gold medalist found a drop-in game in Cherry.

“There wasn’t a more pure skater in college hockey or pro hockey at the time than him,” Sertich said. “His edge work was phenomenal. He reminded me a lot of the Russian players the way they would gain speed on their turns and in spins and stuff like that.”

A true character

According to those who knew Pavelich during his days as a Bulldog, you knew the All-American cared for you if you were the target of one of his pranks.

“To know him and to be an object of his pranks and stuff like that is priceless, absolutely priceless,” Sertich said.

Sertich recalled being on the end of a memorable prank by Pavelich after arriving late to practice at the DECC one day after teaching a class. The then-assistant UMD coach arrived surprised to see everyone in the locker room yet and not on the ice.

Little did Sertich know there was a surprise waiting for him in his locker.

“I open up my locker door and that damn grouse comes flying out that locker,” Sertich said with a laugh.

Pavelich was as comfortable in the outdoors as he was on the ice, his teammates recall. Former Bulldogs defenseman Curt Giles — now the head coach at Edina High School — said it was common for Pavelich to show up early before a bus trip to practice his fly fishing technique in the parking lot.

“We’d be waiting for the bus up at the top of the school where we lived and Pav would be out there practicing with his fly fishing rod,” said Giles, a Bulldog from 1975-79. “He’d have a weight on the end of it and practice fly fishing until the bus would come. He’d break it down, put it back in his bag and away we’d go.”

Giles said the summer between Pavelich’s freshman and sophomore year, no one had heard from or seen him the entire time until just before school started. The team was gathered outside the athletic building prior to the start of classes, and Pavelich finally pulled up in his two-door Maverick.

“There he was, full head of hair and a beard. He looked like Grizzly Adams,” Giles said. “Everyone was glad to see him, excited to see him. We walk over to his car, he opens the car and the smell — just the worst smell came out of that car. I looked in the backseat and there is a fish laying on the floor. I don’t know how long it had been there or what kind of fish it was.”

In addition to hockey and the outdoors, Pavelich also played the guitar, and the instrument nearly got him in trouble with coach Herb Brooks during the leadup to the 1980 Winter Olympics in Lake Placid, New York.

We are saddened to hear about the passing of 1980 Olympic gold medalist Mark Pavelich. We extend our deepest condolences to Mark’s family & friends.

Forever a part of hockey history. 🇺🇸 pic.twitter.com/xS04DMGtLd

— USA Hockey (@usahockey) March 5, 2021

John Harrington — a teammate of Pavelich’s both at UMD and on the 1980 Olympic team — recalled a trip to Dallas with Team USA and everyone being on the bus at the airport except for Pavelich. Brooks sent Harrington back into the airport to find his former UMD teammate, who was still at baggage claim waiting for his guitar.

“Everybody is going, ‘Holy smokes we’re late, Herb is going to go crazy,’” Harrington said. “We walked on that bus and I swear to God, everybody on the team had their head in their coats and in their hands and going, ‘John, we can’t stop laughing here.’ Herb was steaming up there shaking his head and it was because Pav couldn’t find his guitar. It was hilarious.”

‘A loving, caring kid’

Giles, who played 14 seasons in the NHL, said Pavelich might have been one of the best players he’s ever played with. Pavelich’s lateral movement on the ice was second to none.

But his skills are not what made Pavelich such a great teammate.

“He was really giving, too, he really was,” Giles said. “He was really one of those guys that would do anything for the team. I mean anything you needed from him, he’d give you. He was a really good guy.”

Harrington saw the same thing in Pavelich, whether it was at UMD or on the 1980 U.S. Olympic team. It’s what stood out to him the most.

“Nobody was more committed to a team being successful, regardless how how he did,” Harrington said. “For Mark it was more about everybody else. He wanted everybody else to do well, because he knew if he did that, he knew the team would do well and that’s what he wanted to have happen.”

The later years of Pavelich’s life were marred by a criminal case against him for an alleged assault of a neighbor at his Lutsen home in August 2019. Since his arrest, he was undergoing mental health treatment.

In a Facebook post following his death, Pavelich’s sister, Jean, wrote that her brother’s brain is being sent for analysis, which could determine whether he had chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE.

While to the general public, Pavelich was often categorized as a “recluse” for not enjoying or seeking out the spotlight like many of his 1980 Olympic teammates — but instead shunning it — his Bulldogs knew him as the complete opposite.

“He didn’t let everybody into his life, but if you were in there with him, he was a very, very loving and caring kid,” Sertich said. “And that’s the part to me that is so overlooked through all of this.”

Credit: Source link