Jimmy Carter has long been cast as one of America’s least-effective modern presidents—blamed for failing to tame inflation, solve the energy crisis, or free the American hostages in Tehran. His crushing reelection defeat in 1980 sealed the downbeat narrative.

But that negative assessment is beginning to change. Recently, Washington Monthly contributing editor Timothy Noah hosted a conversation between Jonathan Alter and Kai Bird, two journalists who just published major biographies of America’s 39th president. Each approached Carter from a different angle, but both arrived at a similar conclusion: Jimmy Carter is seriously underrated.

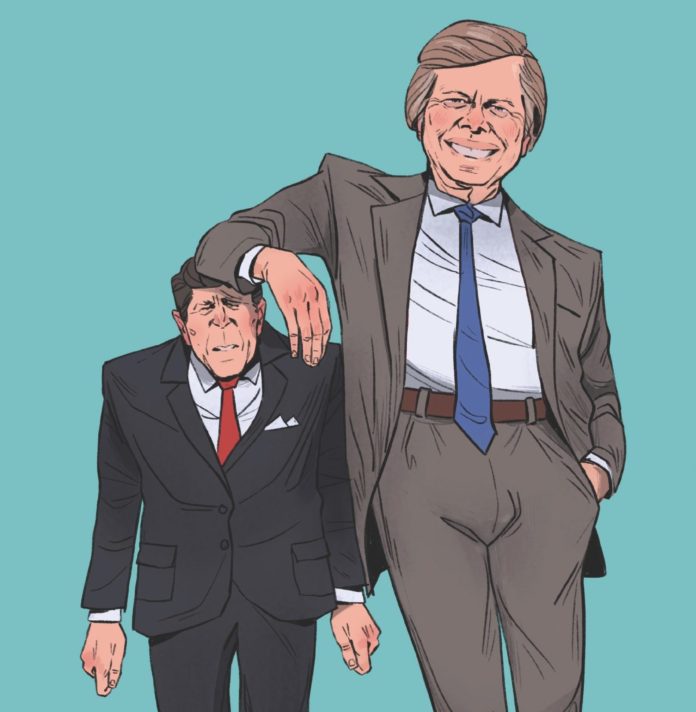

Alter and Bird both dispute that Carter was weak or lost in the weeds, as he has so often been portrayed. Carter brought more positive change to the Middle East than any president in the decades before or since; signed more legislation than any post–World War II president except LBJ; and warned of the dangers of climate change before the threat even had a name. Carter’s human rights policy played a huge and largely uncredited role in the collapse of the Soviet Union—more so, perhaps, than any policies enacted by his successor Ronald Reagan.

What follows is an edited transcript. We promise an absorbing and informative read about some recent history that you almost certainly don’t know as well as you think you do—assuming you remember it at all.

Timothy Noah: It’s my pleasure today to introduce two old friends, Jonathan Alter and Kai Bird, to reassess the presidency of Jimmy Carter. Alter and Bird are the authors of two recent Carter biographies, His Very Best and The Outlier, in which each of them argues for a reconsideration of the former president’s administration. Carter is now 97 years old, which makes him the oldest ex-president in history. Rosalynn, his wife, is 94.

As it happens, the late 1970s is when I first met Jon and Kai. For the record, Jon and I met my freshman year in college, and Kai and I met when I was a summer intern at The Nation in 1979; Kai was my boss. I later succeeded Jon as an editor of the Washington Monthly, and Kai and I reconnected after he and his wife, Susan, moved to Washington, D.C.

I’m going to turn this conversation over now to Jon and Kai, asking Jon to begin.

Jonathan Alter: One of the most pleasurable parts of [this experience] for me was getting to know Kai. We met at the Carter Center Weekend in 2016. To my mind, [we] were engaged in basically the same larger project, which is to get the country to reassess Jimmy Carter, not just as a president but as a person. I think we’ve made some progress on that.

I think the period of time that has elapsed since he left the presidency 40 years ago is about the same as it took to reassess Harry Truman’s legacy. Truman left office in 1953 as a really unpopular president. When David McCullough’s book came out about him [in 1992], it began a true revisionism. I don’t think it’s going to be quite the same level for Carter that it was for Truman, but the reappraisal is under way, and long overdue.

The Carter administration prioritized human rights to an extent that no previous president had done, and this was an extraordinarily important thing. It helped lead to the end of the Cold War, as Larry Eagleburger acknowledged, as Colin Powell has acknowledged. When Václav Havel would give interviews, he would describe how important it was for the morale of dissidents to know that they had a friend as president of the United States. There are a lot of human rights organizations that arose, not just in the Soviet Union but in many other countries where when you talk to the people who started those organizations, they mention Carter.

There’s a story about a prisoner of conscience in the Soviet Union who Carter gets released in a prisoner swap, and he comes to church with him in Plains, and when they’re in church, he’s sitting next to Rosalynn, and he pulls from the fake sole in his shoe a little picture that he kept in there of Jimmy Carter, the whole time he was

in prison.

TN: Wow.

Four American presidents (from left): Richard Nixon, Ronald Reagan, Gerald Ford, and Jimmy Carter share a toast at the funeral of Egyptian President Anwar Sadat in 1981. (National Archives)

JA: So ideas have power. This is important to remember, even in the wake of the war in Afghanistan. You’re hearing some talk of human rights there, but having spent 20 years in Afghanistan, everybody’s now saying, “Well, we can’t, we can’t solve every human rights problem.” Carter would agree with that. It was a very pragmatic policy and situational policy.

That means he did what he could, which was a lot, particularly in Latin America, which went from mostly authoritarian to mostly democratic in the 10 years after Carter was president. That’s not all attributable to him, but he should get some credit for it. There are still many more democratic countries in the world now than there were in 1980. And it’s because of a lot of hard work by people who, in a surprising number of cases, were inspired by Jimmy Carter.

Kai Bird: I would agree with that. Human rights was a major achievement by Carter. He put human rights, that principle, as a keystone of U.S. foreign policy, and none of his successors have been able to walk back from that or ignore it completely. They’ve talked about some of the hypocrisy and impracticality of the policy, but you can’t ignore it. I make this argument in my biography, that human rights, the talk about human rights, and the focus on dissidents in the Soviet Union, and in Czechoslovakia, and Poland—all of that did much more to weaken the Soviet empire in eastern Europe than anything Ronald Reagan did by increasing the defense budget or threatening Star Wars. The Soviet Union was a weak adversary, not a strong adversary. It was falling apart, and along comes Carter, talking about human rights, and as Jon has said, ideas are powerful, and this idea remains powerful, and it really contributed monumentally to the falling of the Berlin Wall and people seizing power in the streets, and wanting to have personal freedom. That, in part, can be attributed to Jimmy Carter.

TN: The Carters recently celebrated their 75th wedding anniversary in their hometown of Plains, Georgia. You were both in attendance. What was it like, and what did you learn?

JA: They’re the longest-married presidential couple in American history. They’ve been married now longer than [were] Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip, which everybody thought was some kind of world record. They actually met three days after Rosalynn was born, almost exactly 94 years ago, when Lillian Carter, Jimmy’s mother, brought her nearly three-year-old son around to see the baby that she had just delivered down the street. They didn’t really see each other very much for the next 20 years, though. They started going out when he was at the Naval Academy.

What really struck me about the delightful wedding anniversary was how small-d democratic it was. It was a real contrast to, say, the Obama 60th birthday party. And not just because, you know, they weren’t cutting close aides from the list. Yes, Garth Brooks went, but it was not that kind of event. It was also a mending of old wounds, because Bill and Hillary Clinton, who hadn’t gotten along at all well with the Carters, came, as did Nancy Pelosi. I have this enduring image in my mind of [Pelosi] going up to Carter in his wheelchair and putting her hands on either side of his face and looking at him long and hard, and you knew that she was thinking, “This is the last time I’m ever going to see Jimmy Carter.” So there was a poignancy to it.

Carter at his 1946 graduation from the Naval Academy, with his then fiancée, Rosalynn (left), and mother, Lillian Carter (right). (National Archives)

They split us up into classrooms at the Plains High School, so that the party had an intimacy to it before we joined the larger group in the school auditorium. In my classroom you had everyone from Lucy Johnson and Sam Donaldson to Rosalynn’s hairdresser and a young Georgia researcher that they had befriended because they liked his nature research. It just really gave you a sense of the scope of their interests, and the fact that they—I wouldn’t describe Jimmy Carter as humble; I don’t think any politician is humble—but the modesty of his circumstances and their approach to life was on striking display.

KB: Jon, just to jump in on that theme, in my classroom I was in the presence of a billionaire who had befriended Carter 25 years earlier and helped to fund the Carter Center and fly him around Africa in his efforts to conquer guinea worm disease, but also in the room were his fly-fishing buddies. This family from Pennsylvania that he, during the presidency, he would go up to visit occasionally and go fly-fishing with. And the billionaire explained to me rather sheepishly that the Pennsylvania fly fisherman couple were Trumpists—they voted for Trump!

JA: The fly fishermen run kind of a legendary lodge in Pennsylvania. [Carter went there] right after the 1980 convention. It was also the location of a story that Paul Volcker told me. I interviewed him not long before he died, and he said that he was at the same fishing lodge when Carter was there a few years after the presidency, and Volcker said, “I’m sorry if I cost you the presidency,” because, you know, he jacked up interest rates, they went as high as 19 percent. How was Carter supposed to get reelected when interest rates were so high? When inflation was vanquished, Reagan was in office and got all the credit. Arguably, Volcker elected and reelected Ronald Reagan. But Carter turned to Volcker, and, with a smile, he said, “There were many factors, Paul.”

KB: Volcker was certainly right up there. Another factor was his treatment by the media. One of the reasons Carter is so misunderstood is, alas, the press that he got at the time, and specifically The Washington Post, [which] sort of mocked his southern heritage—his funny accent, his dress, his demeanor, his talking, his staff from Georgia. Sally Quinn, in particular, the queen of the Style section at the time, and married to [the editor] Ben Bradlee—just went after, relentlessly, Chief of Staff Hamilton Jordan and [Press Secretary] Jody Powell.

Jimmy Carter fly-fishes in the Grand Tetons during a family vacation to Wyoming in 1978. (National Archives)

JA: Kai is absolutely right about this, and I was really surprised to see the tone of the coverage, which influenced me at the time. What I concluded [was] that Carter was both made and unmade by Watergate. He never would have been elected president without Watergate. He starts running just a few months after Nixon resigns, and he is the antidote to Nixon. He says, “I’ll never lie to you,” “We need a government as good as its people.” He [later] said he got a better press than he deserved in 1976 because he matched the moment so perfectly. But then when he gets to office, you have a Washington press corps that is determined to prove that he’s just another Nixon, and that anybody who has that job is by definition corrupt.

KB: Remember Peanutgate? That became a sort of mini scandal that was [much] ado about nothing. And yet the Washington press corps pursued it thinking that they [could] prove that Jimmy Carter used funds from this peanut warehouse illegally in his campaign. It was young reporters like us, always trying to be Woodward and Bernstein.

JA: I had been an intern in Jim Fallows’s office in the summer of 1978. He was not yet 30 years old, and he was Carter’s first chief speechwriter, and that was what got me into the whole Washington Monthly circle, and changed my life, getting to know Jim. I left the White House very influenced by the extremely critical article that Jim wrote for The Atlantic later that year, which I think you and I have different takes on, called “The Passionless Presidency,” and—

TN: I’d like to interject here Jim’s great joke—he probably regrets telling it: “Being Jimmy Carter’s chief speech writer was like being tap dance instructor to FDR.”

JA: Yeah, that was a great line.

TN: Was that a fair comment?

JA: Let’s put it this way. The speechwriters were so downgraded, in terms of their importance in the Carter White House, that I was able to write a later piece, I think for the Monthly, entitled, “I Was a Teenage Presidential Speechwriter.” They would give me speeches to write for Carter, and Carter wouldn’t deliver them, or he would muff the line. I wrote a speech that he gave at a tobacco warehouse in North Carolina, and he ended up saying, “We’re going to make cigarette smoking even safer than it already is today.” He was just really bad at prepared speeches. He didn’t value prepared speeches; he didn’t value rhetoric. Both Kai and I use the diaries of this wonderful guy named Jerry Doolittle, who I got to know that summer, who was the gag writer and a speechwriter. Jerry is very acidic in his contemporaneous diaries about Carter’s speeches. This hurt Carter, especially in contrast to Reagan, who was such a great performer. His delivery was bad. He didn’t have an ear for language. He cut out anything that could possibly be seen as Sorensenian in its rhetoric.

I remember that summer Jim said to me, “Here’s the line you need to use. ‘We must stop inflation, and we must do it now.’ ” That was Carter’s idea of a speech.

I was so disenchanted with Carter that I supported Ted Kennedy in [the] 1980 [primaries]. And then later, [I] thought that was a really stupid thing to do, taking this perfectly fine, not-perfect president and subjecting him to this kind of challenge from within his own party. I was ashamed of having done that.

I didn’t really think about him very much until I was in a book club in 2014 in New York, and we were reading Lawrence Wright’s terrific book, Thirteen Days in September, about Camp David. And somebody knew Carter in our group, knew his grandson Jason, and brought [Carter] to our book group, and this guy was 90 years old [and] delivered this brilliant analysis, not just of Middle East politics, but a tour of the horizon. And in reading that book I realized, this was a virtuoso performance at Camp David. This was one of the great diplomatic achievements in American history. So there has to be more to this guy than “mediocre president, great ex-president.”

My editor at Simon and Schuster was the late Alice Mayhew, and she was Carter’s editor. So when I mentioned this to her, she said, “You have to do this. Nobody’s written his biography.” I didn’t know Kai, it was a little bit before Kai undertook this, and there was this huge hole in the line of scrimmage.

[Editor’s note: A third major Carter book (President Carter: The White House Years) would be published in 2018. The author was Stuart Eizenstat, Carter’s domestic affairs adviser.]

I was in the Carter Library one day reading documents, in the summer of 2015, and MSNBC texted me, and they said, “Trump is announcing his candidacy. Go over to a studio [and] analyze this guy coming down the escalator.” So I did that. And I knew this was going to be a really hateful turn in our national life. I didn’t know he was going to be president. But I went back to the library, and I just remember having this overpowering feeling of relief, going back and studying Carter. He was a vacation for me for four years from Trump. Anytime the toxicity of Trump got to me, I would just retreat into Carter, and it really helped motivate me because Carter was the un-Trump in so many ways.

TN: I understand that, Kai, you take a harsher line on [Fallows’s influential Atlantic article, “The Passionless Presidency”] in your book than Jon does. Fallows argued that Carter lacked the big, visionary mind-set necessary to lead the country.

KB: I devote a whole chapter to Jim Fallows. His Atlantic essay, the first essay in what became a long career at that magazine, was regarded by the Carter White House people as sort of a stab in the back. I thought that was an interesting turning point to write about.

I also thought that the Fallows piece was, well, a little sophomoric. Trying to psychologize Carter. And of course the one thing that people remember from that essay was the tennis court. That the president, in Fallows’s reporting, was paying so much attention to detail that he was [even] micromanaging the schedule of the White House tennis court. When you dig into that, it emerges that there was a misunderstanding, it was a little more complicated, and Carter wasn’t spending time managing the tennis court schedule. But that’s one of the stories most Americans remember about Jimmy Carter.

TN: What about the broader critique that Carter was all trees and no forest? [Fallows] might have even talked about [Isaiah Berlin’s essay] “The Hedgehog and the Fox.”

[Editor’s note: “The Passionless Presidency” doesn’t mention the Berlin essay, though others later likened Carter to Berlin’s fox, who knows many things, and his successor Ronald Reagan to Berlin’s hedgehog, who knows one big thing.]

JA: That was just wrong, Tim. I revere Jim, but that analysis did not hold up under scrutiny. Carter is very much, in Isaiah Berlin’s formulation, a hedgehog. He had big ideas, mostly about peace, that pulled together so much of his approach to the world. But he also is very focused on detail, so this was used as a slam against him.

It’s true that sometimes, particularly when he was governor, he would get into a level of detail that wasn’t very productive, and micromanagement that didn’t help. [But] he really didn’t do that very much as president. What he did do is pay enormous attention to legislative and diplomatic detail. [Without that,] he never would have had the Camp David Accords, he never would have had the Panama Canal treaties, which prevented a major war in Central America, he probably wouldn’t have had normalization with China—instead of devoting a chapter to the Fallows episode, I devoted a chapter to normalization with China. Carter was right in there on the details of that negotiation.

We never would have had the Alaska lands bill, which doubled the size of the National Park Service. Carter was down on his hands and knees with the maps on the floor of the Oval Office, and when Ted Stevens, the senator from Alaska, came in and tried to buffalo him and tell him, “I’ll vote for the bill if you exclude these areas,” Carter said, “No, those are the headwaters of this, and there’s habitat there.” In a limo on the way back to Capitol Hill, Stevens said to an aide, “That son of a bitch knows as much about my state as I do.” If he hadn’t done that, that bill would have been gutted and the developers would have gotten their way.

KB: Jon and I both agree that Carter’s attention to detail was a good thing, particularly in looking at the Trump presidency, where there was no attention to detail. This is what we want in a president. Someone who gets up at 5:30 in the morning, and is in the Oval Office by 6:30, and spends 12 hours reading 200, 300 pages of memos every day, and looking at details, trying to figure out what is the right thing to do.

JA: Where it hurt him, Kai, I think, is when he let that effort to try to get to the right answer crowd out the politics. He didn’t think of himself as a politician, and that really hurt him. I think of him as a political failure because he lost, but a substantive and farsighted success.

But some of his political failings were a result of that assumption that if he could—and Jim did identify this in that famous Atlantic piece—this assumption that if you could get to the right answer, that everybody else would see that it was the right answer and go along with him. So, for instance, on tax reform, which he had promised during the campaign, he sat down, he studied the tax code, he got up at 5:30 in the morning, he knew everything about the tax code and what was wrong with it. And then he dropped a reform bill. He used to communicate through messages to Congress, and he had many of them because he was interested in many, many different issues, and got more legislation approved than any president since World War II—including in recent years—except Lyndon Johnson. He got more bills than Clinton and Obama did in eight years, and many more bills than any Republicans. So there were bill signings every other week, 14 major pieces of environmental legislation, which the press mostly ignored.

But on some big ones he lost, and he lost on tax reform, because he just dropped it on them. [Democratic Senator] Russell Long later said, “He didn’t consult me when he was writing this bill, so why should I consult him when I’m gutting it?”

A smiling President Carter in 1978, after successfully securing the Panama Canal Treaty. (National Archives)

TN: Kai, do you agree that Carter was bad at the politics part of the job?

KB: Well, some of the time—the tax bill is a good example. Another example is dealing with Ted Kennedy on the health insurance bill. It was obvious to Carter, in his view, that Ted was simply looking for an issue to run, to challenge a sitting president for the nomination on, and health care was Kennedy’s big personal issue. Both politicians supported the notion of a national health insurance plan, and Carter was on record supporting Kennedy’s bill. But once he gets into the White House, he’s also a small-town fiscal conservative, and he’s worried about the federal budget deficit. Wrongly, I argued, because he didn’t appreciate Keynes enough. He had the mistaken assumption that the federal budget deficit was fueling inflation, when it was actually commodity prices, the oil increases, the Arab oil boycott, the Iranian revolution. That’s what was fueling inflation.

As a result of this bias on budget deficits, [Carter] told Kennedy that he couldn’t support his bill until his second term in office, and in the meantime, “How about doing a compromise, and we’ll just agree to pass national universal catastrophic health insurance, so that no American family would spend more than $5,000 on a health incident?” Kennedy rejected that, and Carter refused to compromise. In retrospect, I think, Jon, you’re right—if he was being politically smart, he would have let Kennedy walk the plank, and supported his bill, and when it didn’t get the votes that Carter thought it lacked in the Senate, Kennedy’s bill would go down to defeat, and then he could have gotten the universal catastrophic health bill.

Carter signs the 1978 energy bills, which promoted energy conservation and renewable energy in response to the 1973 crisis. (National Archives)

But he didn’t think that way. He just thought, “This is a foolish bill, and I’m going to present the smart bill,” and the result was we got nothing. We got 40 years’ delay in national health insurance. We didn’t get it until Obama, and only partially.

JA: A couple of things that surprised me. Ted Kennedy’s bill was not single payer. There’s this assumption, with progressives now, “Oh, if only we could have had [the Kennedy bill].” [Kennedy’s] bill didn’t even have the votes—Carter was right about this—to get out of committee, much less win on the floor, and it wasn’t single payer. So there was opposition, and what Carter came back with initially was an incremental bill, and Kennedy was very contemptuous of that incrementalism. That’s what we ended up doing under Clinton, with the child health [care bill] first.

Toward the end, Carter introduced his own bill that was really quite a good bill, a little bit beyond Obamacare, and he had the support of all of the key committee chairs in both the House and the Senate. It would have gone through, but Kennedy, who had such authority on that issue, was too proud, and he rejected it.

KB: Kennedy doesn’t come off very well in our books, does he?

JA: Not really. Carter and Kennedy were like oil and water from the time they first met. In Kennedy’s memoirs, he’s very tough on Carter. Carter was trying in recent years to be a little bit more charitable toward Kennedy, and he admitted that he was wrong not to put Archibald Cox on the [appellate bench, which] Kennedy wanted. [It] was very petty of Carter not to do that.

KB: It was a cultural disconnect, the southerner versus the Massachusetts liberal. They just spoke two different languages and they both disdained each other. Kennedy didn’t really understand where Carter was coming from, didn’t believe in his liberal credentials. And Carter thought that Kennedy was a privileged millionaire’s son who thought he was destined to be president.

JA: Carter has never been popular with other politicians. Even when he was in the National Governors Association, he would want the governors, when they were in some sunny clime for their meetings, he would want them to go out and do community service. And the governors were like, “We want to go to the pool, why is Governor Carter making us do this community service, or making us consider these resolutions that are just going to cause us political problems at home?”

President Carter gives a 1979 address on the energy crisis, which came to be known as the “malaise speech.” (National Archives)

He was never a pol. He wasn’t as self-righteous and sanctimonious as some people think in retrospect—he was a huge believer in the separation of church and state, and extremely tolerant of bad behavior in his staff, so he didn’t have that stick up his ass that some people think. But he was all business. That photograph of him standing apart, right after Obama was elected, [with] Obama and the Bushes and Clinton yukking it up and Carter standing aside from them—Kai and I both agree that was really accurate. Carter himself admitted that, and two other presidents, I won’t say which ones, confirmed it. Carter was just stand-offish. When you look at the logs of his calls to members of Congress, he would dutifully make the calls to lobby, but the calls would last, like, a minute and 10 seconds. No time for small talk, he just wanted to cut right to the chase.

KB: Jon, that causes me to ask a question, to steer the conversation toward the art and craft of biography. What were the most valuable sources for your book? How valuable were your interviews with Carter himself?

JA: I don’t think they were hugely valuable, to be honest.

KB: Mine were very disappointing, I have to say. I’d get some color, but in my interviews with him he was so focused on his Carter Center work—projects in Africa or whatnot—he would keep looking at his watch. He was concerned about his historical record, but he was bored with familiar questions, and you showed him a document, it wouldn’t spark a memory. He wasn’t a storyteller.

JA: I agree with that. I did have more success when I went to his house in Plains. When I would interview him at his office in Atlanta, his secretary would come in exactly one hour after the interview started, and it was the old naval officer who’s extremely intolerant of tardiness. So I got a lot less out of those interviews. But when I went to his house we could talk longer.

I learned more from him when talking about his current work—his post-presidency. But I think we both agree that in some ways his post-presidency is overrated because he didn’t have anywhere near the power that he had when he was president to change lives.

KB: Right. I also thought that Doug Brinkley had done a whole book on his post-presidency.

JA: Just one other thing, on interviews. I interviewed 260 people, and I did find that pretty much all of them told me one interesting thing. You wouldn’t get much more than one, but there would be something interesting and unusual that I would always have to check, but that took me in a new direction.

And it was clear from my reporting that Jimmy Carter has led an epic American life. This is an extraordinary human story. When he was president, there was this assumption that there was something a little boring about him, in part because of the way he talked, and the technocratic language that he would use sometimes. The energy crisis was hardly as sexy as the civil rights movement, and he was hardly as compelling personally as Lyndon Johnson or Richard Nixon. But when you look at the totality of his life, not just what he achieved but the complexity of him as a human being, the inability, I think, of either of us—I shouldn’t speak for you, Kai, but I don’t think it’s possible to write a definitive biography of him. His personality is so complex.

We haven’t really talked about him as a person, but this assumption that he was this weak character couldn’t be further from the truth. He was a tough son-of-a-bitch. Not necessarily in a bad way—people didn’t hate working for him. He wasn’t an Andrew Cuomo. But when he bored those steely blue eyes into you, you knew you were in trouble. He was this fascinating combination of his disciplinarian father and his compassionate, although often detached, mother. She was gone so often that he called the desk where she would leave instructions “Mother.” Because she was out of the house, taking care of, often, Black patients, as a nurse.

I also got completely fascinated by the milieu of the South. I had to spend a lot of time stripping off the

sugarcoating that he put on it. He didn’t lie about his early years, but he sugarcoated it. He lived in one of the meanest sections of the whole county. The sheriff, Sheriff [Fred] Chappell, who Carter described as a friend, Martin Luther King described as “the meanest man in the world.” [King spent some time in prison in Chappell’s

jurisdiction.]

I came to think of Carter as having lived in three centuries. He was born in 1924, but it might as well [have been] the 19th century because they had no running water or electricity, or mechanized farm equipment. He was president in the 20th century. Conflict resolution, democracy promotion, global health—these are the cutting-edge issues of the 21st century. Carter has been intimately involved in them for the first 20 years of the 21st century. So the scope of this life, I think, is under-appreciated.

I think [you] explain a little bit more to the reader than I do how useful Carter’s [published] diaries are, that he kept religiously when he was president. They’re really good.

KB: Absolutely. I relied on the diaries and other archival documents much more than interviews, but my main complaint and disappointment, and I’m sure yours, is we both asked for access to the full diary, and we didn’t get it. We got a little bit, but there are 5,000 pages, and he only published 20 percent of it in his 2010 book.

JA: On three or four occasions I requested things that were not in the diaries. For instance, I wanted his reaction in real time when the shah of Iran died, and they provided me those excerpts from the unpublished diaries. There were a couple of other [instances] where I asked for the full entry from that day, and they gave it to me, and actually, the [published] diaries are not whitewashed. I did not find that he took out embarrassing things from the diaries. I was disappointed that he wouldn’t give me his diaries from his post-presidency.

TN: Let me introduce a couple of topics I’d love to see you both discuss. The first is economic deregulation. The other is the Iranian revolution. Does [Carter] have any retrospective regrets on either of those subjects?

KB: Well, the Iran revolution, yes, he has regrets. I write a lot about the Iran revolution. I argue that it was really an organic thing, it was going to happen, there was nothing much that Carter could do to save the Pahlavi regime. It was falling apart, and had become very unpopular by the mid-’70s. Just like we’ve witnessed with the Afghanistan situation, things moved very fast. There’s nothing he could have done to save the shah.

I think his one regret about Iran is that he gave political asylum to the shah. He resisted for months and months. David Rockefeller and John McCloy—the subject of my first biography—and [Henry] Kissinger formed this formal lobbying operation that they dubbed “Project Alpha.” They allocated a budget for it, they hired a publicist, they set up a calendar where each of them would contact at least one high-ranking Carter administration official, if not the president, each week, to lobby for the shah to be admitted. And Carter just resisted it, and you can see in his diary he worries that if he does this, perhaps, the passion in the streets of Tehran will be such that the embassy could be attacked and hostages would be taken. And of course he was right.

He finally gives in late October of ’79, and a few days later the embassy is taken over and we have 444 days of hostages and it’s a body blow to his chances of reelection.

JA: Very quickly on deregulation. He did not engage in deregulating Wall Street in any significant way. This was deregulation of the airline industry, which he did with Ted Kennedy, [and] the trucking industry, which, I argue, set up the just-in-time delivery system that is one of the foundations of today’s economy. And railroad rates—a whole series of industries that his wonkiness led him to do, and he had some really smart people working on it for him, and they did a lot to set up the success of the economy in the ’80s, without really doing any damage. He didn’t do any deregulation on health and safety.

Kai and I both mention a lot of lesser examples. They deregulated the beer industry, allowing microbreweries. But I don’t think that, separate from a few Carter aides, anybody, when they hoist their microbrew, toasts Jimmy Carter. But they should.

TN: The deregulation of the trucking industry was enormously damaging to truckers.

JA: The Teamsters didn’t like it, but—

KB: The same was true of deregulation of the airline industry. It weakened the labor unions that were servicing Pan Am and TWA and the big airlines, and they all went by the wayside, and the airlines that popped up hired non–labor union workers. It was a reform that allowed middle-class Americans to fly for the first time because there were cheaper fares and more choices, and more airline routes. So people like Ralph Nader thought it was a great boon for consumers. But the downside [was] it actually weakened part of the traditional Democratic constituency, trade unions. And this occurred, not only with the airline industry but, as you point out, with trucking and railroads.

[Editor’s note: For more on the consequences of airline and railroad deregulation, see “Terminal Sickness,” by Phillip Longman and Lina Khan (in our March/April 2012 issue), and “Amtrak Joe Versus the Modern Robber Barons,” by Phillip Longman (in this issue).]

TN: It was part of the reorientation of liberalism from employees to consumers. Would you agree with that, Jon?

JA: By coincidence, I talked to Ralph [Nader] yesterday for the first time in quite a while. We talked some

about Carter.

Ralph was pretty disappointed in the Carter presidency, although he agreed with Esther Peterson that Carter was the [most pro-consumer president] he experienced in his adult life. We talked about the failure [to create] a consumer protection agency, which was a big priority for Nader, and to my mind it was The Washington Post, when they editorialized against it, that drove a bunch of liberals away. [Nader] felt Carter could have argued harder

for that.

I don’t think it was deregulation itself, usually on behalf of consumers, that led to this shift [in emphasis from employees to consumers]. I think it was more that Carter never really focused on the problem of deindustrialization, of what would replace the Rust Belt as the engine of the American economy.

The same thing happened with Iran. When the shah started to teeter, Carter failed to apply his normal attention to detail to Iran. He had so much going on. He was planning for Deng Xiaoping’s historic visit. This is in the late fall and winter of 1978, and the beginning of 1979. [The] Camp David Accords fell apart. This is a little-

known fact. After they left Camp David, the whole deal came apart, and in early 1979 Carter had to go to the Middle East, and put the whole thing back together with chewing gum and baling wire and masking tape.

So he has that, he has China. And then there’s this revolt over Bella Abzug, whom Carter had hired to run this women’s commission, and she had used her perch there to attack the Carter administration. So they decided to fire her. And the week that the shah left power, the minutes of the Cabinet meeting, they’re mostly talking about

Bella Abzug.

They really didn’t understand. A lot of people thought “Shiite” was pronounced “shit,” and even Walter Mondale didn’t know what an ayatollah was. So there was this tremendous lack of knowledge about what was going on in that part of the world. And then, to pick up on something that Kai mentioned, there’s all this pressure on Carter to let the shah in. And at one point he says, “Fuck the shah.” He’s really resistant to McCloy and Kissinger and all these people pressuring him. I didn’t really believe that he said this, but when I interviewed [Carter Defense Secretary] Harold Brown, I said, “Did he really say ‘Fuck the shah,’ ” and he goes, “Yeah, I was quite surprised to hear those words out of his mouth.”

But then in October of 1979, [Rockefeller has] a new argument, that the shah has cancer, and must be let in for humanitarian reasons. But this was a con job, and the details of the con job have [only] come out fairly recently. Basically, they pulled the wool over Carter’s eyes and made it seem as if the shah, who was in exile in Mexico, could not be treated for his cancer in Mexico, and could only be treated in the United States. So they let him in. And as Kai said, it was only a few days later that the student militants seized the embassy.

TN: I had always thought that the pressure to let the shah in didn’t happen until after he was a cancer patient. It actually preceded that?

KB: Yeah, from the time he went into exile, from the time that Ayatollah Khomeini came back to Tehran and the shah left, Kissinger and Rockefeller and McCloy were lobbying Carter to give [the shah] political asylum.

TN: What was their argument?

KB: That we had to stand by this friend. If we were seen to be abandoning him, this would send a message to our allies that we were unreliable. It was the standard sort of Henry Kissinger argument about alliances. Carter saw through it as meaningless right away. He understood that this was not the right thing to do, and he only acceded because of—what Jon is referring to is this medical information, which was completely erroneous. [The shah] could have gotten the same or, in fact, he probably could have gotten better health care in Mexico City than in New York City, because the doctors that David Rockefeller set him up with were not experts in what he needed and made one mistake after another.

JA: The doctor was a tropical disease expert!

KB: It was just outrageous.

JA: It’s really a story about [how] celebrities get the worst medical care.

Kai is much harder on [National Security Adviser Zbigniew] Brzezinski in his book than I am. When I interviewed both Kissinger and Brzezinski, I was really struck by the weakness of their argument: that Carter could have bolstered the shah and gotten him to use his army if he only urged him to shoot his own people. This was such a paternalistic bullshit argument. The shah knew enough about what was going on to tell one visitor, “Look, the difference between a monarch and a tyrant is a monarch doesn’t shoot his own people.” He’d already shot some of them during one rebellion. He said, if I start shooting them on one street one week, they’ll just pop up on the next street the next week.

TN: What is the difference between the two of you about Brzezinski? Because you’re not speaking very highly of [him]. Is it about Brzezinski himself or about Brzezinski’s influence on the White House?

JA: The latter.

President Carter meets with the shah of Iran on a visit to Tehran in 1977, about one year before he would flee the country after being overthrown in the Iranian revolution. (National Archives)

KB: No, I’m much harsher on Brzezinski.

During the transition right after the ’76 election, Carter is trying to make his appointments, and Richard Holbrooke calls him. Holbrooke has been giving him advice on his foreign policy change during the campaign, and Carter says, “I’m thinking of appointing Brzezinski as national security adviser and Cy Vance as secretary of state.” And there’s a long pause, and Holbrooke says, “Well, Mr. President-elect, I think you could have one or the other but it would be a mistake to have both,” and he explains that they have two different worldviews.

Brzezinski is at heart a Polish anticommunist who hates the Russians, and believes that the Soviet Union is an evil empire, and that we’re in a generational battle with the Soviet Union. He sees the whole world and U.S. foreign policy through that prism. Whether it’s Cuba or Africa or India, or the Middle East, he’s thinking, “Well, how can we make this bad for the Russians?” That’s his worldview. Cy Vance is much more subtle and sophisticated. He’s learned the lessons of Vietnam. Carter and Vance were on the same wavelength; Carter, though he was a Navy man, he was very averse to military force or interventions. And he found himself agreeing with Vance’s worldview. But he told Holbrooke in that famous conversation, “Oh, that’s all right, I think I can handle differences of opinion.” I think he had in mind [Franklin D.] Roosevelt’s cabinet, which was filled with people who would argue with each other.

But Brzezinski, as I relate, played a very poisonous role in the White House. He was leaking all the time, he was undermining, undercutting Cy Vance, and he was giving Carter bad advice all the time, which Carter usually rejected. Until the last year, when the Soviets invaded Afghanistan. Carter was shocked by that, personally, and at that point began giving way to Brzezinski, taking his advice over Vance’s. That’s why Vance left the administration and resigned.

I argue also that Carter was wrong to accept Brzezinski’s advice about the [Soviet invasion of] Afghanistan. Here we are today dealing with the defeat of a 20-year war. [But] it didn’t start in 2001. It actually started in 1978 and ’79, under the Carter administration, when Brzezinski persuaded Carter to allocate $500,000, and then a little more later. Not much money, but to do a covert operation in Afghanistan to fund the mujahideen, and this is six months before the Soviet invasion.

Brzezinski saw the Soviet invasion as confirmation of an expanding empire, of a Soviet system that was on the move and was aggressive and strong. And this was all wrong. We now know from the Politburo minutes of that meeting, when they decided to invade, that it was a very contentious decision, and that the people in the Politburo who were opposed to invading were appalled to realize that Brezhnev was drunk and senile at the time.

We now know in retrospect that the Soviet Union was falling apart. It was weak. And what were they invading? They were invading to take down a hard-line Communist and put in power a more moderate Communist Party member who would be less alienating to the Muslim culture that was prevailing. It was ridiculous! Brzezinski’s worldview poisoned everything.

JA: I also have a lot about this in my book, and I agree with most of what Kai just said, but a couple of things.

In this 1977 photo, Carter is flanked by National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski (left) and Secretary of State Cyrus Vance (right), who often clashed over the role of anti-communism in foreign policy. (National Archives)

I decided to look at this, not with my journalistic cap on, but to try to put on the hat of a historian, and to not look so much at what the big issues were when he was president, which is the way journalists would analyze it politically, in terms of staff squabbling and all that kind of thing, and look at it instead historically. In retrospect, whole forests died for the newsprint chronicling this bureaucratic rivalry between Brzezinski and Vance. And in the end, Carter rejected almost all of Brzezinski’s ideas, and agreed more with Vance, as he told both me and Kai. But he liked having [Brzezinski] around for the intellectual stimulation. Ultimately that turf fight and most of the other staff squabbling and staffing issues, to me, receded in importance, and I did less on them than trying to assess the long-term effects of [Carter’s] decisions.

Not all those decisions were good. The grain embargo, for instance, which they applied after the Soviet invasion, was disastrous, and Democrats are still paying for that in the Farm Belt, as [Bill Clinton’s agricultural secretary] Dan Glickman told me 40 years later. Because the Soviets quickly started buying grain from other countries, and it was pointless. And obviously the Olympics boycott, which was very popular at first, and a resolution supporting it passed Congress overwhelmingly. That didn’t sit very well with the American people over time. But—

TN: Do you agree that Brzezinski started to break through and have more influence in the last year?

JA: I guess it’s possible that Brzezinski tipped Carter over the edge into supporting [the failed Iranian hostage rescue mission]. But ultimately I don’t think it was Brzezinski’s advice that was decisive; it was the failure of this negotiating track to release the hostages that [White House Chief of Staff] Hamilton Jordan had been spearheading. After that failed in March of 1980, Carter was so frustrated by the fact that they were back to square one diplomatically that he opted for this idea of a rescue mission, which had been described to him since the week after the hostages were seized. They were already beginning to plan a possible rescue mission as a contingency, but it took many weeks of training and development, and then Carter and Brzezinski told them to add a helicopter, but they should have added two. I still think it wouldn’t have worked. The helicopters crashed in the desert, didn’t even get to Tehran. If they had gotten there, extracting the hostages would have been very difficult. A lot of people would have been killed, possibly including the hostages.

KB: Jon and I agree about the craziness of the helicopter rescue mission. It could never have succeeded. It was always going to be a disaster. There were too many moving parts, it was too complicated. And if they had gotten into the streets of Tehran, there would have been a shooting battle, and people would have died.

But I think Jon and I still have fundamentally different assessments about Brzezinski. I’m thinking of the spring of ’77, early in the administration, you can see Carter being pestered by Brzezinski with these memos, saying, “Mr. President, you need to do something tough to show the Russians that you are made of mettle. Something militaristic.” And Carter writes in the margins, “Like Mayaguez?”

[Editor’s note: In 1975, Cambodia’s Khmer Rouge seized a U.S. merchant vessel, named the Mayaguez, and captured its crew. In response, the U.S. launched a bloody and ultimately unnecessary battle to rescue the hostages. (The hostages were not on the island the American military attacked, and they were released when operations began.) Forty-one U.S. soldiers died in the fight.]

JA: Okay, so, Kai, what’s the enduring historical importance of Brzezinski’s advice if Carter told him to get lost? Why does it matter that much?

KB: It matters to readers because it’s really interesting, that there’s this difference of opinion. It’s color—I agree. But it also takes on a historical significance because Brzezinski was relentless. This was his message all the time, and it was debilitating, and it eventually warped Carter’s own response to events. In September ’79, remember the much-ballyhooed Soviet brigade in Cuba? Brzezinski went berserk on this, and tried to tip Carter into a real confrontation over Cuba. Finally [Carter] realizes after a briefing from Mac Bundy and John McCloy that that Soviet brigade—we always knew it was there, we’d agreed that it could be there in the aftermath of the Cuban Missile Crisis in ’62. It was all much ado about nothing. That was the one moment when Brzezinski, seriously, according to his own memoirs, threatened to resign.

JA: I agree with all of that, but to me the critical figure in that sorry episode was [Idaho Democratic] Senator Frank Church, who was chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, facing a tough reelection fight that he would lose. He and a number of other formerly liberal members of Congress also went crazy on this ridiculous Cuban brigade story—

KB: True, true.

JA: —so I don’t think that Brzezinski was decisive. Where I do think he was important—and this is an area where we disagree—is that he wanted to be another Kissinger. He had this rivalry with Kissinger, so he went to China in advance of normalization and he negotiated at least some of the normalization. Leonard Woodcock and another negotiator/diplomat did most of it, but Brzezinski made an important trip. He was acing out Holbrooke—there’s great stuff in George Packer’s [Holbrooke biography] about that particular trip—but he says to the Chinese, “The first one to the top of the wall gets to fight the Russians.”

Why do you think that normalization was inevitable? I believe that’s what you write in your book, and you devote less than a paragraph to it. You say this was going to happen. My feeling is that [if] Gerald Ford, who was so afraid of the right wing that even after he had been defeated and his political career was over, he resisted entreaties from Senator Phil Hart’s widow to pardon draft dodgers—Carter did that in his first week as president—if Ford had been elected [to another term], there’s no way he would have defied Reagan and the right wing and thrown Taiwan under the bus the way Carter did, and normalized relations with China. That normalization is the foundation of the global economy. Carter thinks it’s the single most important, most enduring thing that he accomplished in office. I’m just curious as to why you think it would have happened anyway.

KB: I think you’re right. If Ford had been, he would have been under pressure from the right wing not to, quote, “abandon the Taiwanese.” But there were larger historical economic forces at work. Carter did win that ’76 election, and there was no disagreement among his team. Henry Kissinger was in favor of normalization. Cy Vance was, Brzezinski was in favor. There was no argument about it; there was no internal tussle. Everyone was in favor of it, and so was Carter, and I think it was going to happen.

Carter shakes hands with China’s Vice Premier Deng Xiaoping in 1979, during a series of signings that normalized Chinese-American relations. (National Archives)

This is coming back to what I said at the beginning, we come at these issues with different passions and interests, and when I saw that there was no internal argument inside the administration, it became a less interesting story for me to write about. I think I gave more than a paragraph to it. I think it is important, but it was inevitable. Politically, it was going to happen, and it did happen, and Vance was—coming back to the rivalry—he was offended by Brzezinski’s behavior, and [by] being jabbed in the stomach bureaucratically [when] Brzezinski finagled the trip out to China, undermining the secretary of state. Brzezinski was doing this all the time. So that was, I think, something to write about. I just found the story less interesting than you did. But there’s no surprise to that. We’re going to find different things.

I devoted a whole chapter to the October Surprise. A little cautiously, with some trepidation, because it’s a conspiracy theory and it’s complicated, but I was fascinated by the story, and you decided to give two or three paragraphs to it. I don’t think we basically disagree about what may or may not have happened. But I thought it was worth a short chapter.

[Editor’s note: The October Surprise theory holds that Reagan campaign staffers conspired with Iran to delay the release of the American embassy hostages in order to damage Carter’s reelection chances.]

JA: To be honest about it, my book, with footnotes, was 782 pages, and it was originally 1,100 pages, and my publisher wouldn’t even let me submit it unless I cut 300 pages. So I had to make some hard choices on that.

But, Kai, I agree with you. Tim, I think this was after you left Newsweek, but in 1991 Newsweek did this, in retrospect, terrible cover story trying to debunk the October Surprise theory. Both Kai and I fastened on this now-deceased reporter named Robert Parry, who in 2013 came upon a 1991 White House memo mentioning [that] in the summer of 1980, [Reagan’s campaign manager] Bill Casey was in town for reasons the U.S. ambassador to Spain didn’t know. And the entire Newsweek cover story debunking the October Surprise theory was based on the idea that Casey never went to Madrid. But it turns out he was in Madrid.

Gary Sick, who was Carter’s top adviser on Iran—he wrote a whole book on the October Surprise—told me the reason that he couldn’t really prove the case [was that] all the hotel records and the other records that would have validated a meeting between Casey and the Iranian regime were destroyed. Casey had been head of the CIA, [and Sick thinks] it was pretty short work for him to destroy all the incriminating evidence. Unfortunately, the Iranians who were at these meetings—their reliability is close to zero. So at the end of the day, as Kai said, we’re left in the same place, which is that it probably happened. But [we’re] never going to prove it.

There are, however, some things we know for sure. There was a guy named Joseph Verner Reed, who became head of protocol under Reagan, and then he was an ambassador under Bush. This Rockefeller-crowd guy, who I have—[Kai,] your venom for Brzezinski, I direct at this guy Joseph Verner Reed. He wrote to his family after the election, “I’m proud of my role in doing anything I could to delay the release of the hostages until after the election.” I mean, here these people are sitting in a dank basement. They’ve been in prison for 444 days, ultimately, and he’s proud of the fact—this pillar of the American banking establishment is proud of his role in keeping them imprisoned in Tehran. It’s disgusting.

KB: That’s pretty disgusting. But the other guy who’s still around is C. Boyden Gray.

JA: He’s a bad actor in this also.

KB: He was White House counsel under George H. W. Bush when Congress was investigating this October Surprise. There was a congressional task force led by Lee Hamilton, a very respected [Democratic] congressman from Indiana, and [the committee] had subpoena power, and they subpoenaed any records pertaining to Bill Casey’s travel in the summer of 1980. The subpoena forced the State Department in 1991 to make a search of its records.

Hamilton should have gotten some useful information from that search. The White House memo Parry discovered in 2013 relied on State Department information. It mentioned a cable from the Madrid embassy that reported that “Bill Casey was in town for purposes unknown.” The Madrid embassy cable, however, was never turned over to Lee Hamilton’s congressional task force. He wasn’t even aware of the cable until I told him about the 1991 White House memo in an interview. Hamilton then told me, “I was never given [the cable]. They never showed it to me. We subpoenaed it, and I never got it.” No one has been able to find the actual cable, just the memo noting its existence.

JA: In my conversation with Lee Hamilton—he’s very old, but he was kind of pissed.

KB: Yeah, he was angry about this.

JA: He [said], “They made a monkey of me.” He put in all this time in this investigation and they hid the key document from him.

KB: I asked for an interview with Boyden Gray, who’s alive and well in Washington, D.C. He never responded. I sent him a letter telling him this was appearing in the book; he never commented. He thinks he can get away with this, and he has.

This brings us to why did Carter lose the 1980 election? And I think one contributing factor was dirty works by Bill Casey. This meeting in Madrid where he allegedly met with a representative of the Ayatollah Khomeini, and assured him that the Iranians would get a better deal from his guy, Reagan. That was one reason [Carter lost]. The other reason was Kennedy’s challenge, which we’ve talked about, and how he weakened Carter going into the national campaign. Carter’s aides often told me that he lost in 1980 because of the three Ks: Khomeini, Kennedy, and [former New York City Mayor] Ed Koch.

TN: Ed Koch?

KB: Why Ed Koch? We haven’t discussed this, but I write a great deal about this in my narrative. I thought it just fascinating that Carter had this difficult relationship with the Jews. The New York Times had an editorial entitled “The Jews and Jimmy Carter.”

He had a difficult time with the Jewish American establishment, and with people like Ed Koch, who thought that he was anti-Israel. This started even before Camp David, but it went on after Camp David—after he had taken Egypt off the battlefield for Israel, and made this triumphal piece of personal diplomacy that resulted in a real, long-lasting peace treaty—although a cold peace—between Israel and Egypt.

The reason is that Carter continued to pressure the Israelis on the settlements. And why? Because he believed, ardently, that he had gotten [Israeli Prime Minister Menachem] Begin to promise a five-year freeze on settlements in the West Bank. If that was true, then that makes it not just a separate peace between Egypt and Israel; it turns it into a comprehensive peace settlement that involves the Palestinians. It provides a road map to Palestinian autonomy, self-determination—they weren’t using the [phrase] “two-state solution” at that point, but that’s what everyone understood it to be. If you continue to build the settlements, Carter realized, that was going to close down the option [of] a two-state solution.

So for the next 40 years, he was very outspoken about this, and he pissed off a lot of Jewish American leaders, who are still angry with him. In Zoom meetings promoting my book this summer, it was astonishing how, in the chat room, you can see questions—they never pose them directly to me, the moderators are too polite to do that—but you can see in the chat room that questioners are saying, “Well, isn’t Jimmy Carter an anti-Semite?” The reason it’s a hot-button issue is that the Jewish American establishment hasn’t spoken out to defend Carter. In fact, they make a point of criticizing him for his pressuring Israel on the settlements: “You shouldn’t do that, this is an Israeli decision that should be done on their own terms.”

TN: Even retrospectively, looking back over the history of the last 40 years on settlements?

KB: J Street now exists, and J Street recently gave an award to Jimmy Carter, which was an extraordinary thing in the Jewish American community, and very controversial.

TN: I’m asking about your Zoom conversations, though. Did you hear anybody actually deny that the last 40 years of settlements have been catastrophic in the Middle East?

KB: No one argued with me on Zoom, but in the chat box you could see people saying that.

JA: The settlements [are] not what this is about. I deal with it at considerable length, and Kai, just in terms of Ed Koch—he had endorsed Carter and then sniped at him. Jane Byrne, the mayor of Chicago, endorsed Carter and then basically endorsed Kennedy after that.

KB: Right.

JA: And Hamilton Jordan said if Jane Byrne and Ed Koch had a baby, it would have all the qualities of a dog except loyalty.

We could both write whole books on this subject. I also focus on this misunderstanding at Camp David, which I think was partly the product of intense fatigue.

TN: Do you both agree it was a misunderstanding as opposed to a betrayal by Begin?

JA: Yeah.

KB: No.

JA: You think it was a direct betrayal? You think that [Begin] flat-out promised?

KB: I believe Carter. Carter believes that Begin promised him, and that he deceived him. He either lied or he deceived him.

JA: The promise is not really in the documents. It came down to a distinction—

KB: It was a side letter, and they had agreed to a side letter that said five-year freeze on the settlements.

JA: No.

KB: Begin had agreed to sign that. Then he substituted the letter.

JA: What the actual language had was a freeze on the settlements for the length of the negotiations before a treaty. The Camp David Accords were not a treaty. They set up a process, and the treaty wasn’t signed until the following March of 1979 after, as I mentioned, Carter had to go back to the region. There was a lot of work done. It had to pass the Knesset.

Begin’s understanding—which he did, actually, renege on—was that he wouldn’t do anything with the settlements for the five months before a treaty. Carter thought that was until there was a final status agreement, five years later. If Carter believed that Begin was really not going to do anything for five years, he was being naive about that, in an otherwise brilliant performance.

I think the real hostility from the Jewish community, which, as you said, has existed all along—Carter is the only modern Democratic president who didn’t receive more than 50 percent of the Jewish vote—

TN: Wow.

JA: That was in 1980.

KB: Yup, only 45 percent.

[Editor’s note: Reagan captured 39 percent, so Carter still won a plurality of Jewish votes.]

JA: —so all these bad feelings existed then, I think in part because a lot of them rejected Camp David. A lot of American Jews said, “You gave away the Sinai? [The Camp David Accords] hadn’t endured yet.” Now you can look back, and—what I say is that even though Jimmy Carter is the most critical of Israel of any American president, he has been the greatest president for the security of the state of Israel since Harry Truman. Because, as Kai mentioned, by taking the Egyptian army off the battlefield, he secured Israel. When I was growing up as a Jewish kid in Chicago, we would hear all the time, “Israel’s in danger of being driven into the sea.” There was only one army that could drive Israel into the sea: the Egyptian army. You never hear that anymore. It’s just gone from the vocabulary. That’s because of Jimmy Carter.

KB: But the settlements are important even today. This is why Carter’s presidency is still relevant on this foreign policy issue. He has been so prophetic in warning that if you build settlements, you change the whole nature of the conflict, and you change the nature of the Jewish state. It will no longer be a democratic Jewish state. It will become an apartheid state. He actually used the word in the title of his book in 2006 that pissed off

everybody.

Egyptian President Anwar Sadat, Carter, and Israeli Prime Minister Menachem Begin sign the 1978 Camp David Accords, the Carter-brokered peace deal considered to be a critical achievement of his presidency. (National Archives)

JA: That’s what pissed people off. That’s why you and I both got these questions, “Is Carter an anti-Semite?” Because of the title of that book, Palestine: Peace Not Apartheid.

I remember at the time, 2006, kind of going, “Wow, that’s pretty harsh.” But it turns out that not only Ehud Barak, a prime minister of Israel, but many members of the Knesset use that word, apartheid, on almost a weekly or monthly basis.

KB: But Jewish American leaders wouldn’t.

[Editor’s note: After our conversation, Bird elaborated on this topic in a September 15 op-ed in Haaretz titled “Why Are U.S. Jews Still Calling Jimmy Carter an Anti-Semite?”]

JA: At Camp David, when he went to the region in ’79, even though he was much closer to [Egyptian President Anwar] Sadat, he was nonetheless an honest broker. But after that, after he left the presidency, he sided almost entirely with the Arabs, and he wasn’t even welcome in Israel; nobody would meet with him when he would go there. And then, when he met with Hamas, that really sealed it. But I think perceptive Israelis understand where this comes from.

My book is not as focused on the Carter presidency as Kai’s—I have a lot more about his early years. My basic argument is that he spent the second half of his life making up for what he didn’t do in the first half. He didn’t stand up for civil rights when he was running for governor in 1970. He issued dog whistles. He praised George Wallace.

So as president, he launched his human rights policy. Years later, Karl Deutsch, the great Harvard professor of international relations, ran into Carter—Carter was depressed after he left office—and said, “President Carter, hundreds of years from now you will be remembered because your government was the first in human history that made the way other governments treat their own people an issue for your government.” Carter cried after he heard this. The policy was hypocritical, but it was enormously important. As Andy Young says—America’s embrace of international human rights was a globalization of the civil rights movement. The way Israelis analyze this, smart Israelis, is really accurate. They say that Carter’s attitude toward the Israeli-Palestinian conflict grows out of his regret over having lived on land in Georgia that was stolen from the Indians, and having not stood up enough for Black people in the South, and that he sides with the weaker party, the party that’s been persecuted, and in this case, that’s the Palestinians. That provides his motivation, and he is on fire about this. He’s been interviewed about the Middle East so much that I didn’t use much of my time in my interviews to bring up the Middle East, because it would consume the rest of the hour. His biggest regret about not getting reelected is that he couldn’t complete the work of Camp David and have a comprehensive Mideast peace. I think the greatest regret of his post-presidential life is also that he was not able to make any real progress in the Middle East [as an ex-president].

TN: Am I right in concluding that, ironically, where you both agree is that Carter, despite this rap he gets in the Jewish American community, wasn’t tough enough on Israel, because he didn’t secure that five-year hold on

settlements?

JA: There would have been no deal. They packed their bags three or four times, both sides, to leave.

KB: That’s true, but I still maintain that in Carter’s view, he believes that he had the pledge from Begin to sign this side letter.

TN: Do you think that it’s possible, Kai, that it could have been in [the agreement]?

KB: In 1978 there were probably less than 20,000 settlers, maybe less than 15,000 settlers, in the West Bank. Today there are roughly 700,000.

TN: Right.

KB: By the time Carter left office in ’81, there were 25,000. So, yeah, it would have been a tough issue, but Begin had agreed to remove the settlements in the Sinai. To put a freeze on settlements in return for the promise of a comprehensive deal with the Palestinians—in 1978, that could have been possible. Now, if Carter had been reelected, he would have, as Jon has just admitted, he would have made this a priority. He would have put enormous pressure on the Israeli establishment to come to terms with the Palestinians.

JA: Yes, I think he would have, but I don’t think he could have done it at Camp David. It would have almost certainly blown up the deal if it had been explicit. There’s a big difference between dismantling a few settlements in Sinai, which has no religious significance—

KB: If he couldn’t get it, he was deceived by Begin, who switched the letters. He agreed to sign one letter, Carter thought he had it, and then in Camp David he says, “Wait a minute, this is a different letter.” And he called the Israeli aide to Begin and said, “Go get the original language.” And then there was a delay, and they had by that time scheduled the press conference [on] the White House lawn, and they were getting on the plane to go back. Carter believed he had a deal that included [a] comprehensive [settlement]. Whether I’m right or not, he believed it. And he believed that he was deceived. Or lied to, outright. And this explains much about his attitude in the last 40 years.

JA: It does. But there were conferences later where other Israelis who Carter got along well with—unlike

Begin—said, “Come on, it’s one thing to relinquish some settlements in the desert in the Sinai, but this is—in the

Bible”—

KB: Judea and Samaria.

A White House photograph of Carter from 1977. (National Archives)

JA: —so there was no way that Begin was committing to do that. And that Carter should have understood that. And that everybody was super tired on day 13. But I agree with you that, if he had been reelected, he would have not only pursued Middle East peace, he would have achieved it. Because, having been reelected, he would have paid any price to knock heads together, threatened to cut off aid to Israel, whatever was required, to get a comprehensive settlement.

KB: Particularly after Sadat was assassinated. He believed Sadat sacrificed his own life because of this.

JA: But he also said, interestingly, that Israel gave up more at Camp David than Egypt did. And that these were tough concessions for Begin to make. It was a huge amount of acreage.

In the other “What if?” category is climate change. If Carter had been reelected, he would have pursued Middle East peace, and he also would have begun to pursue a climate change agenda.

At the very end of his presidency, there was this thing called “Global 2000.” The [White House] Council on Environmental Quality, run by a guy named Gus Speth, released a report on what was sometimes called carbon pollution. Carter had started studying the issue in 1971. I found in his files from when he was governor underlinings in the journal Nature about carbon pollution and global warming. Other politicians played golf—Carter played tennis—but he was reading scientific journals. That’s how he got his jollies. So they issue this report. What’s amazing about it is that the reduction in CO2 that they recommend be the policy of the Carter administration is precisely what was in the Paris Climate Accords of 2015. Would we have fully embraced it? Would he have repudiated coal? No, because we needed coal at that time to achieve energy independence. But he would have surfaced global warming as a major issue. He was the first leader anywhere in the world who considered it a problem.

KB: It would have been a different world if he had had a second term, and we hadn’t had Ronald Reagan for two terms. That’s a great historical counterfactual.

TN: That’s a very good point on which to end the conversation unless—let me check in with both of you—do you feel as if you’ve exhausted the topic?

KB: We have not exhausted the topic!

[Laughter.]

JA: Each of us spent five years on these books!

Credit: Source link