Susan Grossman likes to remember her father as a true Renaissance man.

Dr. Richard “Dick” Mathewson, father to Grossman and her brother Stephen, lived up to that title in both acts of his life.

In his first act, Mathewson, a Michigan native who ended up in Oklahoma, became a founding member of the University of Oklahoma’s School of Dentistry, leading the charge in pediatric dentistry in the state. In his second act, a post-retirement Mathewson became skilled in a number of hobbies, including researching and repairing antiques, teaching his children to fly fish and growing abundant vegetables in his garden.

A cornerstone of Oklahoma’s dental community, Mathewson leaves a formidable legacy in his field after his death from COVID-19 last month. Dick Mathewson — a pediatric dentistry pioneer, lover of antiquities and genealogy, and devoted husband, father and grandfather — died Dec. 3, 2020 at 86 after contracting COVID-19 and suffering a fall. Mathewson is one of 115 Norman residents who have now died in relation to COVID.

Mathewson’s career in dentistry began back in his home state of Michigan, where he met his wife Alice, began his family and obtained degrees from multiple Michigan universities. While the family moved multiple times in Mathewson’s early career, his interest in pediatric dentistry eventually landed them in Norman.

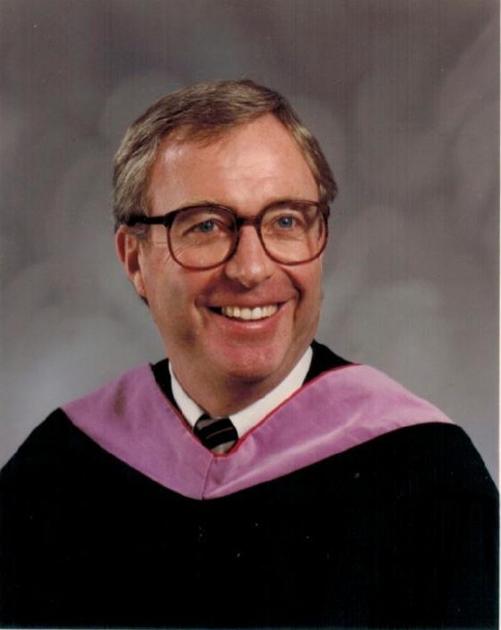

Mathewson, by then a recipient of multiple degrees, joined OU’s College of Dentistry as a professor, chair of the Department of Dentistry for Children and director of General Dentistry at Children’s Hospital.

Dr. Richard “Dick” Mathewson teaches in a photo his family believes was taken in the early 1970s.

Dr. Terri White, who knew Mathewson as a professor, mentor and eventually, a friend, said Mathewson was “a pioneer” in many ways at the dental school, introducing a computerized system for student record keeping.

“Of course, not every student that went through the College of Dentistry became a pediatric dentist, but I think he felt that everybody should be kind of on an equal footing and have a good understanding of what was needed to treat children and how to do it properly,” White said.

Mathewson taught his students how to accurately care for children, breaking through the notion that children were just small adults and instead showing that children needed different support and care.

“He wanted his students to know that children aren’t small adults — the whole stigma about going to the dentist, he just really resisted,” Grossman said. “He hated that — he didn’t like dentist jokes. He just thought that dental care was such an important part of overall health.”

Mathewson also became a beloved and influential professor at OU, co-authoring a pediatric dentistry textbook and earning a Regent’s Professor title and two Professor of the Year honors. Grossman said she’s heard from several of her father’s former students since his death.

“They all just said, ‘your dad had a tremendous impact on me and my career, and I will always be indebted to him,’” she said.

“We always knew grandpa was around”Mathewson retired in the mid-90s, putting an end to a distinguished career in dentistry and stepping into a new era in which he embraced hobbies like antiquing, fishing and studying his family’s genealogy. He eventually wrote a book on Buffalo Bill Mathewson, a distant family relative.

Dr. Richard “Dick” Mathewson fishes on a trip to the Conejos River in 1990. Mathewson “always said he would prefer to pass away while in mid-cast on a trout stream,” his daughter said (photo provided by family).

Mathewson was a man of his generation — quiet and gentle, not one to talk too much. But he was also a man who cherished the accomplishments of the people he loved. He was proud of Grossman and her brother Stephen, proud of his grandkids, proud of his students and colleagues like White, Grossman said.

When Grossman returned from a stint living in Europe in the late 90s, her dad was there for her, she said. He was there to help when a kid woke up sick, there to drive Grossman’s daughter to high school, there to attend recitals and concerts.

“We always knew grandpa was around — my house was two blocks from their house, so we lived close by, and he took care of my yard for me because I’m not a yard person,” Grossman said. “He did all of that for me, and he taught [the kids] how to fish and … they just knew that he was around, and then when they had stuff in school, if I needed my dad’s advice on things he would weigh in. He was just a good grandpa.”

Grossman’s longtime partner Jim Miller, who lost his parents 20 years ago, said Mathewson served as a second father to him.

“I kind of adopted him, actually, as my dad,” Miller said. “Dick was a real gentle soul. He was an academic extreme — he said he has more degrees than anybody I’ve ever known. He was kind of a real gentle soul, real educated, but this sweet, sweet man. and I just, I always liked him — we just had a natural friendship.”

“They are not statistics”Over the last years of his life, Dick Mathewson’s sharp academic mind was met with the challenges of dementia. His family began to notice some personality changes as his mind changed too.

“He became quite sweet and affectionate and very loving, and they become a little childlike — I mean, he just lost his ability to speak in sentences, so he lost his ability to use words,” Grossman said. “But before that my dad was always … very well spoken and educated and curious, and he was really proud of my brother and me and his grandkids, and he would really just do anything that we needed him to do for us.”

Dr. Richard “Dick” Mathewson pictured on Father’s Day 2017.

Mathewson and his wife Alice eventually moved into separate long term care facilities — Mathewson, to Arbor House’s Reminisce facility, where he could receive memory care, and Alice to Grace Living Center. The family still brought Mathewson home for dinner every Sunday, serving him his favorite beverage of red wine with ice.

Then came the pandemic. Mathewson’s family was only able to see him and Alice through the windows of their long term care facilities, standing in the mud to communicate through the glass. When Alice died in summer 2020, Mathewson didn’t know about his wife’s passing until he read her obituary in the newspaper.

“That day, after he read the obit about his wife, he was just devastated,” Miller said. “He was so upset, crying, and I’d never seen him like that before. and then we went out a couple days later, and we got to actually go see him, and we took a bunch of pictures of her and him together when they were younger. That was pretty touching.”

Before and on Thanksgiving, Mathewson went multiple falls, and also contracted COVID-19. After his last fall, which left him with a head injury, Mathewson was taken to the hospital. Grossman was unable to be there with her father or advocate for him in person, and found it difficult to reach staff by phone for updates on her father’s condition.

About a week into her father’s hospitalization, Grossman called the hospital, reached a doctor, and was told that Mathewson died 20 minutes before her call. Doctors said Mathewson had a lung clot that had traveled to his heart and that they were unable to treat with blood thinners because of his recent head injury.

“It’s like something you could not even have envisioned that would happen to your parents, that they’re going to die alone, and my poor, sweet little dad was in a hospital for a week and unable to tell us or tell anyone, ‘where’s my daughter, where’s my son? What’s happening? Can you call them for me? He couldn’t do any of that,” Grossman said.

Grossman said it’s been immensely meaningful for her and her family to see President Joe Biden’s administration honor those who have died in the pandemic. When the administration lit 400 lights at the Lincoln Memorial this month, pausing to remember the 400,000 dead, Grossman’s family was moved to tears.

“Thank goodness we are now acknowledging the pain and the suffering people are going through and telling these stories, it’s so important,” Grossman said. “These are people. They are not statistics.”

Credit: Source link