Lewis W. Butler, an inventive modernist residential architect with a prominent clientele, died Thursday, after a battle against esophageal cancer.

Butler, a fourth-generation San Franciscan, died in hospice at home in an 1884 Victorian home he had gutted and remodeled with his wife and architectural partner turned novelist, Catherine Armsden. He was 63.

In a 35-year career at Butler Armsden Architects, Butler established himself as an independent risk-taker. He built his first house, a fly-fishing cabin on Fall River (Shasta County), while an undergraduate studying civil engineering at Stanford University. Later, after earning his master’s in architecture from Harvard University, he opened his firm in San Francisco in 1985, drawing clients by word of mouth from the start.

Butler Armsden is now a firm with 27 residential architects and a portfolio of high-end homes designed for Silicon Valley tech luminaries who often require a nondisclosure agreement. This deprived Butler of a considerable amount of publicity in architectural and design magazines, which never bothered him in the slightest.

“He was just thrilled to be sitting in the same room with these highly talented captains of industry, talking about home design,” Armsden said. The ideas were often beyond the common realm of architecture, but Butler was able to pull them off with an enthusiasm and energy that could persuade discerning San Francisco planners and neighborhood traditionalists.

“His strength was that he always exuded confidence and a can-do attitude,” Armsden said. “Lewis’ firm was known for being an exceptionally happy place to work because every idea was respected and everyone was given independence on their projects. He never had a boss’ arrogance.” He did, however, have a great sense of humor and a self-effacing charm.

Lewis Wohlford Butler was born March 27, 1957, in San Francisco, the middle of three kids of Lewis H. and Sheana Butler. He grew up in Jordan Park, but when he was 4 his father was hired to be the assistant director of the Peace Corps in Malaysia, and the family lived in Kuala Lumpur for three years. When he returned he attended Madison School, but was pulled out again when his father took a job in the Department of Health Education and Welfare in the Nixon administration in Washington D.C.

Back in San Francisco, he bounced between high schools while spending most of his time on his back, under the engine of a 1929 Model A truck he was rebuilding and owned until his death. The only way his parents could get him out from there was to pack him off to boarding school at Andover, Mass. There, he fell upon an unexpected passion for archaeology and drafting, “and his brain just clicked on,” Armsden said.

He arrived at Stanford in the fall of 1975, planning to major in architecture, only to be told that there was no architecture major. So he switched to civil engineering, and also walked on to the varsity soccer team, spending two years as a goalie. The Model A truck became something of a mascot for his crowd, and he rode it into election as one of four senior class presidents.

After graduating, he worked as a draftsman for William Turnbull architects until he left for Harvard the following year. During his first semester at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, the desks were arranged alphabetically, with Butler close to Armsden, from Kittery Point, Maine.

As a test, Butler subjected Armsden to a cross-country drive in a 1963 Cadillac without air conditioning. After a 10-day trip, Butler turned in the Cadillac and introduced Armsden to the riding luxury of the Model A truck.

Three weeks after completing their last project, they were married in a backyard on the hottest September day on record in Maine, then drove across the country a second time. They rented a one-bedroom apartment on Telegraph Hill, and Butler opened his firm by carving space out of the building’s store room.

He started with one client, his father, whose grandmother had purchased two $5,000 lots in Seadrift at Stinson Beach when it was first developed. Butler designed a shingled beach house that became the family vacation home.

The simple H-shaped design with a pitched roof has been copied around Seadrift and in beach towns around the country. It remains the most published project on the Butler Armsden website 35 year later. Also popular is the Yolo County Cabin, a farmhouse that incorporates a water tower in its design, and his Valley of the Moon Retreat, a Sonoma home with a concrete base that allowed it to withstand the wildfire that devastated the area in 2016. That project won an American Institute of Architects Award. Butler won many awards over his career, but they sat in a pile leaning against a wall. He was never the type to brag about awards.

“Lewis was a gentleman in all of his interactions,” said Chandra Campbell, CFO at Butler Armsden on Sutter Street. “Even if a prospective client hired another firm, he would always say, ‘You can reach out to me any time if you want another eye on your project or other advice.’ He was always helping or mentoring anyone who reached out to him.”

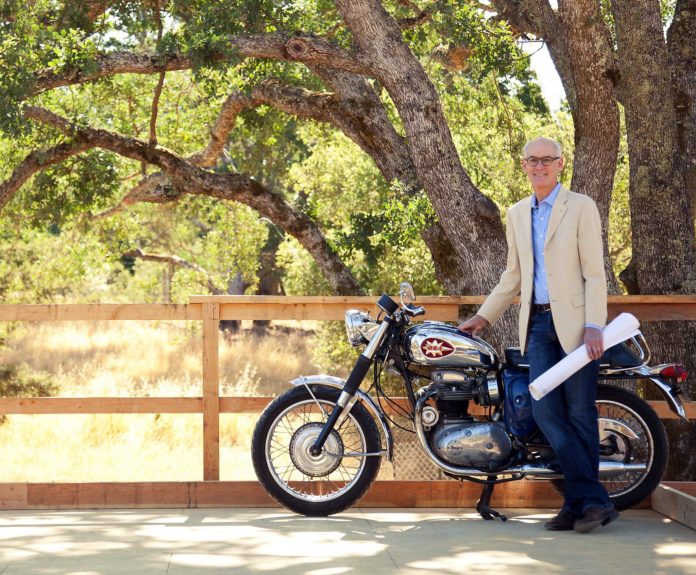

The only thing that Butler enjoyed more than figuring out a house to build was taking apart a vintage British motorcycle. Using Craigslist and eBay, he built a hobby out of refurbishing BSA and Triumph bikes from the 1970s. A vintage BSA still sits in the offices of Butler Armsden. There was also usually a family dog in the office and often one or both of his children, Elena and Tobias. For most of his career, the office was one block from home, so he could always make it to dinner.

Butler was also a surfer, and when the waves were up he would drive out to Ocean Beach. In the cold water, waiting for the sets, he developed a group of friends completely separate from his on land friends.

Butler served on the boards of the Hamlin School, University High School and the San Francisco Girls Chorus, helping each of them with renovation and remodel projects pro bono. He also was active in building sand castles at Ocean Beach as a fundraiser for LEAP, a nonprofit that brings art and architecture into Bay Area public schools.

Within the past year, Butler started having problems swallowing food and lost his ability to speak, but still kept up a furious work pace by email.

Butler’s son, Tobias, is a software engineer at Change.org. His daughter, Elena, took a leave from medical school at the University of Pennsylvania in order to come home and care for her father in the Victorian.

“He was a parent who made you feel like any problem you might have he could help you solve it,” Elena said. “Right up until the end he was affectionate and proud of what we were doing with our lives.”

Survivors include his wife of 37 years, Catherine Armsden of San Francisco; daughter Elena Butler of Philadelphia, son Tobias Butler of Oakland, father Lewis H. Butler of San Francisco, sisters Serra Simbeck of Portola Valley and Lucy Butler of Los Angeles, and four nephews and three nieces.

A memorial service will be held in 2021. A scholarship fund for underserved youths interested in studying design and architecture is being set up at Butler Armsden in care of Chandra Campbell at ccampbell@butlerarmsden.com.

Sam Whiting is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: swhiting@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @SamWhitingSF

Credit: Source link