Shelley, the blithely optimistic young narrator of Kathryn Ma’s The Chinese Groove, leaves Gejiu, Yunnan Province, accompanied by echoes of his father’s “little stories:” “My tender-hearted father! Storyteller, weaver of dreams, the kite that Mother had flown. When she was alive, I used to hear Father murmuring to her… about his hope for a Shangri-la, a Peach Blossom land, where strangers were welcome and love drifted down like petals and everybody, high or low, clever or stupid, rickety-boned or ox-like, everybody got along.”

This Peach Blossom fantasy accompanies Shelley on his journey to San Francisco, where his new realities unfold in evocative, sometimes unsettling, sometimes comic adventures. He is sustained throughout by a belief in a “kind of knowledge, passed wordlessly through the ages and residing in the bones.”

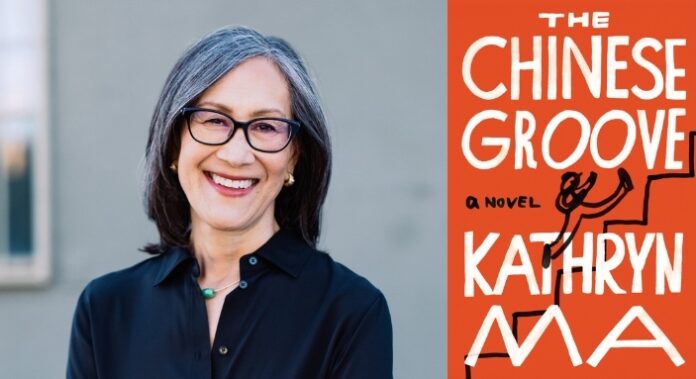

“Shelley believes that there’s an unspoken bond between ‘countrymen’ in the Chinese diaspora wherever they reside,” Ma explains. “He dubs that bond ‘the Chinese groove,’ placing great faith in ancestral and cultural ties that he hopes will protect him as he leaves home and embarks on his grand adventure.

On the plane ride to San Francisco, he thinks, wrongly, that the Chinese groove is winning him special treatment. Uh oh, the reader thinks. He’s got this all wrong. This could spell trouble. But maybe Shelley is onto something. Are there ties that bind? Can fellow countrymen be trusted? Can he persuade his distant American relatives that they’re bound to him via groove when they don’t want to house this confounding teenage boy?”

These questions are one thematic layer in an exquisitely wrought family saga. Our conversation took place via email in Pacific time, at the dawn of the new year.

*

Jane Ciabattari: How has your life evolved during these past few years of turmoil and pandemic?

Kathryn Ma: I learned how to adapt to circumstances I never imagined, which gives me new insight into my immigrant parents’ experiences of surviving radical change. Their challenges were greater than mine, but I have their example to buck me up when I sink low. My novel’s main character, Shelley, has their resilience. I also learned that sustaining community requires effort. You’ve got to reach out and open yourself to the odd idea that writing, which is solitary work, is also a group practice. A circle of writing pals fuels the work and nourishes the spirit.

JC: Were you working on The Chinese Groove during this time, or was it already set for publication? How was the launch affected?

Optimism is just a trait. It doesn’t save one from the consequences of one’s actions.

KM: I had a complete draft of the novel by 2020 and was working on revisions. It went through many drafts. To my good fortune, Dan Smetanka of Counterpoint Press bought the book in the summer of 2021. My editor, Dan López, and I quickly developed a great working relationship. I’m really happy with the outcome. Dan L. understood from the start that I wanted to encompass humor, joy and sadness, which allowed me a broad tonal range.

JC: Shelley is an optimistic eighteen-year-old when we first meet him in 2015. He’s heading for San Francisco to make his fortune as a “cool guy and a poet.” He expects to move in with a rich uncle, owner of a department store, “and figure out from there foot in the door and student visa and green card,” as his father puts it. What fuels Shelley’s optimism? What motivates him to come to the US? Is the fact he was treated rudely by his Zheng relatives (he was born into the “despised branch of the family”) a factor? His generation? His mother’s dream for him? His temperament and talents?

KM: Shelley was inspired in part by an upbeat young man I met on a trip to Shanghai. He was irresistibly cheerful, undaunted by various obstacles and smart. He navigated the world with unusual brio, and that stayed with me. Shelley’s bad circumstances motivate him to leave home and try his luck in San Francisco. But some folks are born with a cheerful disposition, and Shelley is one of those people. I think they’re a rarity. I don’t find them often in fiction. Dickens’s optimists are often fools, and Shelley’s no fool. It was great fun to write a character who has that verve, though I had to modulate his enthusiasm. He does meet failure, and he has to wise up. He makes plenty of bad choices. Optimism is just a trait. It doesn’t save one from the consequences of one’s actions.

JC: Shelley’s cousin Deng has told him that “poets in America get fancy cars and special housing, revered as they were by their fellow citizens as keepers of the famous American freedoms.” Shelley has a “foolproof plan” as he heads to San Francisco. He will polish up his English (already A-plus from studying for many years) and win back his California girlfriend Lisbet. How is it we realize even as he announces it that this dream is unlikely to come true? His innocence? Naivete? Youth?

KM: Shelley’s storytelling style lets the reader know that his blithe view of the world is about to collide with reality. I found his voice early. He has a breezy way of speaking and narrates with confidence. He loves language and wordplay, and he uses Shelley-invented words or phrases (like “the Chinese groove”) to bend usage to his own purpose. We know he sometimes misreads a situation. It’s like watching a friend head off in the wrong direction. You want to call out to them, but they can’t hear you because they’re too far down the road. Sooner or later, they’ll discover their mistake. It might be a disaster, or it might turn out to be funny. Either way, there’ll be a story to tell.

But sometimes Shelley sees things more perceptively than others. He has the outsider’s advantage of fresh perspective and emotional distance. When is he reliable and when not? I like that the question is always present, keeping the reader guessing.

When is he reliable and when not? I like that the question is always present, keeping the reader guessing.

JC: Soon Shelley has been ousted by his Uncle Ted and his aunt Aviva, who only allow him a two week’s stay, has enrolled at City College, found a job prepping green beans for “Truly Mongolian Green Beans,” the signature dish at Pop Up Veg Out Nicely, and moved into a boarding house. He’s ever the optimist. He can “top and tail five thousand beans and not a scrap falls on the floor,” thanks to training from his aunties. Which skills he developed at home become the most important aspects of his lifeline?

KM: He’s a survivor. He had to take responsibility at a very young age because his father gave up. His Yunnanese family makes him do all the dirty work, and this comes in handy in his new, disrupted life as an immigrant scraping by. The housing crisis that plagues San Francisco (and many other American cities) forces Shelley to bounce from one housing situation to another until he ends up homeless and desperate. Then his talents serve him well. He has to juggle demands coming at him from all directions, much like the comic hero in Goldoni’s The Servant of Two Masters. A Chinese hero from commedia dell’arte. Shelley would have something to say about that.

JC: Indeed! Shelley also has fascinating moments of turning to his reader and foreshadowing the narrative. “You’re worried for me. You, whoever you are. Citizen of the World (since you’re reading this), sympathetic to a boy flying high on a dripping mop. He’s supposed to be in school.” What drew you to make that choice?

KM: Both of Shelley’s parents were storytellers. His mother told him folktales and legends. His father made up stories “out of the chapters of his day.” Shelley takes up where his parents left off and becomes a storyteller himself. He’s also influenced by the legend of the Peach Blossom Forest, a well-known Chinese fable with special meaning in the book. He’s conscious of the fact that he’s telling a story, and that’s why he uses humor, builds suspense and occasionally addresses the audience directly.

JC: What research did you do to trace Shelley’s adventures, which take him to Chinatown and the Sunset District in San Francisco, to Los Angeles? Does this mirror a typical Chinese immigrant’s journey?

KM: In 1999, I traveled with my parents to my father’s hometown in Yunnan Province, China. One vivid memory from that trip—meeting a relative snubbed by the rest of the family—was a starting point for my novel. I chose a different hometown for Shelley and researched the local terrain, food, train schedules, pop culture and more. Once he arrives in the US, everything changes. New problems arise.

I researched San Francisco housing discrimination, political corruption, birth tourism, fly fishing, and the bison who roam in Golden Gate Park. I went to Southern California to explore options for locating a modern-day kibbutz. The hard part about research is having to leave heaps of delicious detail on the cutting room floor. It all contributes to getting the book right, or so I told myself while wandering the Internet, or driving around ranch country.

JC: Family secrets are at the center of your story. What are the most difficult of these secrets to resolve?

KM: Shelley is keeping secrets from his father. He’s too ashamed of his lies to come clean, and he has to dodge and weave to keep the pretense going. How he decides to handle his lies and shame are part of his journey. Other characters in the story have their secrets, too. Several subplots keep the book moving. I imagined them as multiple aircraft flying in different directions that I had to steer home and land at the same time.

JC: What are you working on next?

KM: There’s a scene in The Chinese Groove in which Shelley has a long chat with a silkworm. I’m hoping a silkworm shows up to help me with my next novel. He better come soon. I’ve got a lot of questions.

__________________________________

The Chinese Groove by Kathryn Ma is available from Counterpoint Press.

Credit: Source link