“], “filter”: { “nextExceptions”: “img, blockquote, div”, “nextContainsExceptions”: “img, blockquote”} }”>

Get access to everything we publish when you

>”,”name”:”in-content-cta”,”type”:”link”}}”>sign up for Outside+.

Enjoy this tale from the Backpacker archive

In a suburban backyard in Southern California, Ted Nelson stood among a group of men watching a flock of pigeons soar on a blue-sky Saturday. It was mid-April 2006, and this was Nelson’s first “fly,” a competition among fanciers of Birmingham roller pigeons. Birmingham rollers possess a genetic disposition to roll in midair–they somersault backward so quickly that the birds resemble a pinwheel of whirling feathers. A top competitive flock will “kit,” or fly together like a school of fish, and spin almost as one.

“There they go!” a man hollered as the pigeons began to tumble. “Oh, that’s a nice roll.”

Ted Nelson was new to the world of roller pigeons. Like a lot of Southern California subcultures, the world of “spinners,” as the birds are called, had its own peculiar vernacular, trade secrets, and bitter rivalries. Nelson was a newbie, but he fit right in with his droopy mustache, dirty jeans, and old ball cap. Most of the competitors were blue-collar guys who enjoyed the camaraderie of a shared hobby.

Nelson displayed a newcomer’s curiosity. When he saw a wood-and-wire contraption the size of a doghouse, he asked what it was.

“That’s a hawk trap,” one of the guys told him.

“What do you need that for?” Nelson asked.

Hawks and falcons were a menace to the hobby, the guy said. They preyed on roller pigeons.

“Falcon got one of my birds last week,” another fancier told Nelson. “I grabbed my gun and ran into the street. He was there on the pole, but my neighbor was in the yard, and she’d have called me in. So I couldn’t take a shot.”

Pigeon flies are moveable feasts; competitors drive from house to house to watch the birds spin within their home range. In every backyard he entered, Nelson noticed guns and hawk traps. It seemed like these guys were killing a lot of birds–or at least were armed for it.

“Caught a couple hawks in my trap last week,” one man told Nelson. He said he killed the birds with a pump-action pellet gun. “You want to bag them up and throw them in a dumpster a few miles away,” he said.

Nelson asked why.

“It’s illegal to kill ’em,” the man said. “You get caught, that’s a $10,000 fine.”

In the late morning, the caravan pulled up to Juan Navarro’s house. Navarro was president of the National Birmingham Roller Club, the hobby’s nationwide association. He lived in Los Angeles in a million-dollar house near the edge of Griffith Park, a 4,200-acre refuge full of wildlife. Coyotes, mountain lions, red foxes, and mule deer roam the park’s brushy hillsides, along with humans on 53 miles of hiking trails. The problem for Juan Navarro was the park’s red-tailed hawks and peregrine falcons. They were killing his pigeons.

Nelson asked Navarro if he found hawk traps to be useful. “The first two years I was here, I caught 40 every year,” Navarro said.

Nelson was shocked. “Forty!?” he said.

Later, Nelson asked Navarro what he did with the trapped raptors. Shoot them?

“I don’t shoot them,” Navarro said. “I get a stick and just pummel them.” Then he smiled and told the rookie that eventually he’d understand. “It’s a great thing,” Navarro said. “You’ll see.”

But Ted Nelson didn’t see. Though his face didn’t show it, he was sickened by what he heard.

At the end of the day, Nelson climbed into his car and drove to a nearby McDonald’s. He turned off the surveillance equipment hidden under his clothes. He drank a Coke and made notes on what he’d just seen. He called in to the office to let his colleagues know he was safe.

Ted Nelson wasn’t just a curious hobbyist. His name wasn’t even Ted Nelson. It was Ed Newcomer. He is an undercover wildlife cop. And the men he’d just spent the day with were about to enter a world of trouble.

If you are a poacher or a wildlife smuggler, if you sell turtle-skin boots to Houston oilmen or Caspian caviar to Beverly Hills matrons, chances are good that one day you’ll meet Ed Newcomer. You won’t know it when you do. He’ll greet you as a suburban dad, or a scruffy longshoreman, or a Hollywood prop wrangler. He’ll take his time to win your confidence. It could take months. It could take years. That’s okay. Ed Newcomer is a patient man. Over time, he’ll infiltrate your operation so completely that you’ll laugh and brag that the cops could never touch you. That’s when Ed Newcomer will open his wallet and show you his badge, the one that says U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Special Agent, and tell you that your world is about to collapse.

Ed Newcomer is a wildlife detective in Los Angeles. His beat is Southern California, a sprawling territory that includes the Mojave Desert, the Tehachapi Mountains, the Salton Sea, the Hollywood Hills, 500 miles of coastline, and a 200-mile-wide swath of Pacific Ocean.

Newcomer works undercover. You don’t know his face, but if you’re a hiker who thrills at the sight of a black bear in the woods, or a hawk soaring above a meadow, or a butterfly floating along the rim of the Grand Canyon, you enjoy the fruits of his labor. According to the World Wildlife Fund, the $6 billion trade in illegal wildlife is the second-biggest threat to the survival of endangered species. (Habitat destruction is first.) Between 1996 and 2001, more than 6 million wild-caught live birds, and 7 million wild-caught live reptiles, were exchanged on the global market. Much of that trade is fueled by American dollars and American collectors.

The job of combating that trade falls to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, whose special agents–like Newcomer–are considered the best in the world. Newcomer came to my attention a couple of years ago through a brief newspaper story about the capture of Yoshi Kojima, the world’s most notorious butterfly smuggler. From the late 1990s until 2006, Kojima acted like a one-man endangered species wrecking crew, running a black market that hastened the demise of some of the planet’s most beautiful creatures. Kojima boasted that no customs agent or cop could bring him down. Then Ed Newcomer picked up the case. Working undercover for three years, he gained Kojima’s confidence so completely that the two nearly became business partners. And then one day a special agent opened his wallet and arrested the butterfly man. Newcomer’s case was so solid that Kojima didn’t even contest the charges in court.

“He’s the best undercover agent I’ve ever worked with,” says Joseph Johns, the Assistant U.S. Attorney who heads up the Department of Justice’s environmental crimes division in Southern California. “He can think on the fly, and he knows exactly what the best evidence is and how to get it. It’s a lethal combination.”

When he’s not in character, Newcomer is a trim, compact 42-year-old Colorado native who carries himself with the ironed-shirt crispness of a prosecuting attorney, which he once was. Though you’d never guess it, he’s a martial arts expert who’s a good bet to be the last man standing in a bar fight. “I was always small for my age, so I figured getting a black belt would be a good way to defend myself,” he says.Newcomer speaks softly, with a laconic Western accent that he uses as a tool to put suspects at ease.

He works out of the USFWS’s Southern California law enforcement office, located in Torrance, not far from Los Angeles International Airport. Newcomer looks at a map of Southern California like a mouse surveying a cheese factory.

“I love L.A.!” he tells me, sitting in an office overstuffed with case files and the tools of his trade: an underwater camera, camouflage pants, walkie-talkies. “It’s a great place to be a wildlife agent. Throw a stone, you’ll hit a wildlife crime.” LAX is one of the world’s largest ports of entry. Parrots, iguanas, and other exotic beasts are smuggled across the Mexican border. Rhino horn powder moves through Chinatown. He’s tracked butterfly thieves to the Grand Canyon and gone after reptile poachers in Joshua Tree National Park.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service special agents function like detectives without portfolio. For the most part, they develop their own investigations by following up tips from a network of informants. That’s how Newcomer’s most recent, and strangest, case came about. It was called Operation High Roller. It started with a phone call.

“Ed, we just took in a red-tailed hawk,” said a staffer at the California Wildlife Center, a Malibu clinic for sick and injured animals. “It’s been shot.”

Newcomer took down the information and tossed the file on the pile. “Ninety-nine percent of shot-hawk cases are unsolvable,” Newcomer later told me. “The hawk gets shot, flies away, and dies.”

The next week, during an idle moment, Newcomer dialed up the man who had rescued the bird. The guy had no idea who pulled the trigger.

“But you know what’s funny?” he told Newcomer. “I found another hawk in my yard a couple days ago, and this one’s dead.”

That piqued Newcomer’s interest. “What’d you do with it?” he asked.

“Put it in my freezer.”

The man lived near the Van Nuys airport in typical San Fernando Valley sprawl: tract house after tract house, broken up by the occasional tract house. After interviewing him, Newcomer quickly identified a suspect: a pigeon breeder who lived next door.

Marty Ladin was the pigeon fancier’s name. Ladin was too curious and too cooperative by half. “What did the neighbors tell you?” he asked Newcomer. “What would happen to somebody who did this?” Then Ladin started vibing creepy. “You carry a weapon?” he asked.

Newcomer nodded. In his head, red flags were waving like May Day in China. He ended the interview cordially, convinced that Marty Ladin was his guy. But aside from a frozen hawk corpse, Newcomer had no evidence. So he cooked up a plan.

He had Ladin meet him for another interview. At this one, Newcomer brought two videotapes. He put them on the table as he talked.

“You ever notice that street light near your house?” Newcomer asked Ladin. “It’s got a camera in it. When you shot that hawk, we were looking at you.”

The two video tapes were blank. There was no camera.

The bluff worked. Ladin confessed.

At the time, Newcomer was still the rookie agent in the Torrance office, even though he was 37 years old. He’d joined the Fish and Wildlife Service after a stint as a state prosecuting attorney in Olympia, Washington. “In order to do undercover work you’ve got to have brass balls,” says Marie Palladini, Newcomer’s former boss. Palladini, who recently retired as head of the Torrance office, is now a criminal justice professor at California State University, Dominguez Hills. “You’ve got to be creative and a little theatrical. When Ed pulled that bluff I knew he was going to do great things.”

Marty Ladin paid a $5,000 fine for shooting two hawks, a violation of the federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act.

Something kept nagging at Newcomer, though. “During our interview, Marty told me about these pigeon clubs,” he later recalled. “They’re all over Southern California. Hundreds of guys. If Marty’s got a problem with hawks, I’m thinking every pigeon breeder has a problem with hawks.” Newcomer did the math. If hundreds of breeders were each killing a handful of raptors, that added up to thousands of hawks and falcons killed every year.

He told Palladini he wanted to play his hunch. She was skeptical. “Follow it up,” she said. “But don’t spend too much time on it.”

In Undercover, former Secret Service agent Carmine Motto’s classic guide to the trade, Motto cautions that the initial meeting is crucial. “The most important time during the whole undercover case is the first five seconds when the suspect is introduced to the agent,” he wrote. “It is these first few seconds when the suspect makes a personal judgment and decides whether or not he wants to do business.”

I once asked Newcomer how he handles the first meeting. “Do you reel off some elaborate back story?” I said.

“No, no, no,” he said. “You keep it as vague as possible. If you and I met, and within an hour I’d told you everything about my background–what I did for a living, whether I had a wife and kids, where I lived–you’d find that a little strange. In real life, people don’t offer up a whole lot of personal information.” It helps, he said, to go in as a novice rather than an expert. “That way your curiosity as an agent is the same as your natural curiosity would be as a new guy.”

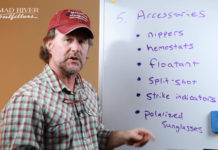

To infiltrate Southern California’s pigeon breeding circles, Newcomer made himself into Ted Nelson, a blue-collar worker with a mustache straight out of My Name is Earl. Through a roller pigeon website, Newcomer made contact with a fancier who invited Ted to a show. That weekend, dozens of members of the Inner City Rollers Club gathered in an alley behind The Pigeon Connection, a bird shop near Inglewood, to check out each other’s pigeons. Newcomer wired himself up–”I can’t tell you the specifics,” he told me, “but video cameras these days are so small you can practically stick one on your wristwatch”–and walked in.

Newcomer spent six hours at the Pigeon Connection show. Nearly every breeder he met told him that they trapped hawks, shot hawks, and killed hawks. One man had developed a poison paste that he smeared on the back of his pigeons’ necks. Another man sold $10 “pigeon jerseys” made out of fishing line. When a falcon strikes the pigeon, explained the entrepreneur, its talons get tangled in the line. The bird panics and drops to the ground. “At which point,” he told Newcomer, “you can take out all your frustration.” The salesman executed the falcons with a brutal boot stomping.

Two days later, Newcomer played the surveillance tapes for Palladini. She was aghast. “I’ve been doing some research,” he informed her. “There’s a national group called the National Birmingham Roller Club. The president of the club, Juan Navarro, lives here in Southern California. There are about 250 members in L.A. alone. So far, I haven’t met a breeder who isn’t killing hawks and falcons.”

Palladini was convinced. “We’re talking about a potentially huge impact,” she said. “You gotta work these guys.”

As a kid, Ed Newcomer enjoyed hiking and camping in the Front Range of the Rockies, west of Denver, where he grew up. Other kids played with G.I. Joe action figures. Newcomer played with a toy U.S. Forest Service truck. When he turned 16, his parents gave him an old Jeep CJ-7, and he often spent weekends rambling around the backcountry, exploring Pikes Peak and Rocky Mountain National Park. Wildlife fascinated him. When he wasn’t looking for it outside, he was looking for it inside, on TV shows like Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom and National Geographic. He imagined himself as a martial arts master who wandered the land like David Carradine in the TV show Kung Fu–only he’d battle on behalf of birds and bears.

To state the obvious, Newcomer is living his dream. Unlike Carradine, though, he’s never really seen. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service relies heavily on undercover work. The reason is simple. “There are no informants among animals,” says Newcomer. “A mother bear can’t call me up when somebody poaches her cub.”

Since arriving at the Torrance office, Newcomer has been lucky to learn from a master of the undercover craft, Sam Jojola. Jojola, 58, is the Torrance office’s wily veteran. He’s worked undercover jobs for 25 years, many of those spent with the Fish and Wildlife Service’s special operations unit, which runs long-term international investigations out of the Service’s Arlington, Virginia, headquarters. Jojola has busted everyone from bird smugglers to big-game poachers to Versace fashion pirates.

Jojola once told me why he and his colleagues relied on fakery. “With a drug bust, it’s straightforward,” he said. “The DEA gets the bad guys together with the cocaine, arrests them, and sends them to jail. But in a lot of animal cases, our suspects use the magic words–captive bred–like a get-out-of-jail-free card.” In the exotic wildlife trade, many species can be legally sold if they’re bred in captivity. They’re illegal only if taken from the wild. “The burden of proof is on us to show that it’s not captive bred,” Jojola said.

“Animals can’t talk,” added Newcomer. “So we go undercover and become witnesses to the crime.”

“This line of work requires a lot of creative thinking,” Jojola said. “You’ve got to figure out how to come across as a certain type of person, someone your suspect would want to spend time with.”

The more time “Ted Nelson” spent with roller pigeon fanciers, the more they liked him. Ted got along with everyone. He paid respect to the top pigeon flyers. He made those around him feel like experts.

The feeling wasn’t mutual. The deeper Newcomer got into the hobby, the more he became convinced that hawk and falcon killing was ingrained in the culture. Then he met a fellow Fish and Wildlife Service special agent named Dirk Hoy, who worked out of the Service’s Oregon office, near Portland. Hoy offhandedly mentioned that he was looking into a strange new case. “I ran into this section of society that seems to be killing hawks on mass levels,” he said.

“You’re not going to believe this,” Newcomer said, “but I’m doing the same thing.”

The two agreed to collaborate. “At that point we realized this wasn’t just a local problem,” Newcomer recalled. “This was a Pacific flyway problem. We’ve got hawks and falcons migrating from Canada to Mexico, and all the way they’re getting hammered by these pigeon guys.”

The two agents put out calls to colleagues around the country. Anecdotal evidence indicated that birds of prey were being killed by pigeon breeders in Texas, New Mexico, Minnesota, New York, and Montana.

Newcomer’s outrage grew, fueled by his knowledge of raptor history. From the 1950s to the 1970s, America’s hawk and falcon populations crashed due to the affects of DDT. The peregrine falcon was nearly wiped out; by 1975, there were just 324 nesting pairs in North America. Over the next 30 years, the USFWS, state agencies, conservation groups, and falconers mounted an unprecedented effort to revive the peregrine falcon–bigger even than the campaign to save the bald eagle. It worked. In 1999, with at least 1,650 nesting pairs in the wild, the falcon was removed from the federal list of endangered species. “All that work, and here these guys are blasting them out of the sky by the dozens–maybe hundreds,” Newcomer said.

He sought out the worst raptor killers, the most brazen shooters, and those in leadership positions. “If somebody told me, ‘I’m the president of my local club,’ they were on my radar screen. They’re leading those organizations. People follow what they do.”

Juan Navarro, president of the National Birmingham Roller Club, became one of Newcomer’s primary targets. Early in his research, Newcomer discovered a posting attritubed to Navarro on a roller pigeon website. The post advised that traps had proven successful against Cooper’s hawks, but that heavier artillery was necessary when going after falcons.

Whenever there was a roller pigeon competition, Ted was there. The competitions were tailor-made for undercover surveillance. “Everyone’s walking freely into everyone else’s backyard, checking things out, asking questions,” Newcomer recalled.

Meanwhile, in Oregon, Special Agent Dirk Hoy was uncovering disturbing findings of his own. Over the past decade, Portland has revived its peregrine falcon population by encouraging the birds to nest in the bridges spanning the Willamette River, which runs through the center of the city. The birds have become beloved neighbors to Portland’s half-million residents. Among pigeon breeders, though, the falcon’s revival is a sore subject. Hoy discovered that the breeders weren’t just grumbling about falcons–at least one fancier had shot one of the bridge falcons and bragged online about the “true bliss” it brought him. That brazen attitude made bird advocates furious. “We spend the last 15 years trying to restore these falcons, and they’re out there killing the exact same birds!” said Bob Sallinger, conservation director of the Audubon Society of Portland.

At that point, a disagreement broke out over strategy. Newcomer and Hoy could go deeper into the culture and rack up evidence against more breeders. But more birds died every week. “We didn’t want to let the slaughter go on,” recalled Hoy. “We needed to figure out how to get the best bang for the buck.”

Assistant U.S. Attorney Bill Carter, who was then chief of the Department of Justice’s environmental crimes section in Southern California, pushed for quick arrests. “As soon as you’ve got solid evidence on somebody, I want you to take the case down,” Carter told Newcomer.

Newcomer pushed back. “Look, if we catch one guy killing hawks, he’ll be fined a couple thousand bucks and everybody in the club is going to say, ‘Good thing they didn’t catch me.’ The only way we’re going to have an impact is to show this is an organized, systemic effort that’s condoned by the clubs. Let’s take down as many as we can.”

Carter relented. Newcomer bought himself some time. But he didn’t have forever. He’d have to ramp things up.

As Operation High Roller entered its second year, Newcomer focused on a list of high-profile fanciers. There was Juan Navarro, the national president. Keith London, the Pigeon Connection shop owner. Darik McGhee, the hawk trap manufacturer. And then there was Brian McCormick.

McCormick, a custom-truck enthusiast, kept a kit of roller pigeons in the backyard of his house in Norco, a small town in Riverside County, about 50 miles east of Los Angeles. He was also president of a Riverside-area group, the California Performance Roller Club. After a competition at McCormick’s house, Newcomer sidled up to him and asked for some advice.

“Say Brian,” said the man known as Ted, “I noticed you keep your hawk trap under a tree. Does that work better, when the hawk can come in and perch and drop down?”

McCormick bristled. “I don’t trap hawks,” he said.

A few days later, Newcomer spoke on the phone with Darik McGhee, the trap maker.

“Hey Ted,” McGhee said, “be careful how you talk about hawks in front of the guys. A lot of them get real shy when you start talking about predators.”

Newcomer stepped up his game. “Hell, Darik, I didn’t mean to freak anybody out. But it seems like that’s all you guys talk about,” he said.

McGhee reassured him. “Don’t worry,” he said. “I told them you were okay.”

Newcomer hung up the phone and smiled. He was in so tight he didn’t even have to deflect suspicion. Other pigeon breeders were doing it for him.

To get proof of McCormick baiting his traps, Newcomer and another agent, John Brooks, staked out his house at night. Armed with AR-15 rifles, Newcomer and Brooks donned camouflage suits and used night vision scopes to crawl across an empty field adjacent to McCormick’s yard. One night they were moving across the field when they stumbled into the decomposing body of a red-tailed hawk. The agents suspected it had been shot, but it was impossible to prove.

Traps weren’t McCormick’s only method of killing hawks. During a roller pigeon competition at McCormick’s house, Newcomer spotted a bizarre weapon leaning against a wall. It was a Remington 870 shotgun custom-fitted with an eight-foot barrel. “At one meeting, I’d overheard Brian talking about how he could shoot falcons and hawks without anybody hearing him,” Newcomer told me. “I figured it was because he lived next to the I-15 freeway. But it turns out that the long barrel acts as a silencer. The shot’s no louder than a hand clap. His neighbors never heard him.”

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service agents weren’t planning to go after other members of McCormick’s club. But then one afternoon Newcomer dropped by Rayvon Hall’s house.

Hall had recently purchased a hawk trap from Darik McGhee. Newcomer, posing as Ted, knocked on his door.

“Hey, I’m a friend of Darik’s,” he told Hall. “He said you had great pigeon lofts. Can I check ’em out?”

Hall invited him in.

In the backyard, Newcomer spotted a trap. He asked Hall what he did with the hawks once he caught them.

“Oh, I cut off their talons and throw ’em out,” Hall said.

“Cool!” Newcomer said. “You got any around?”

“Sure.”

Hall walked across the yard and returned with a severed Cooper’s hawk talon. “You can have it,” he told Newcomer.

“How do you kill the hawks?” Newcomer later asked. Then, with a secret audio recorder running, Hall offered up his own indictment.

There’s a school next door, he explained, so he didn’t want to take a chance shooting them. Instead, he told Newcomer, “I put some bleach and ammonia in a spray bottle, then spray the hawk in the face and eyes.” It caused convulsions.

“They flap around, gasp and suffocate, until they die,” Hall said.

Holy shit, thought Newcomer. Rayvon Hall went on the short list.

Assistant U.S. Attorney Bill carter left the agency at the end of 2006. Joseph Johns, Carter’s successor as head of the environmental crimes division, had 18 years of experience prosecuting environmental offenses. He understood the value of symbolism and deterrence.

“With wildlife cases, what you see us doing is just the tip of the iceberg,” Johns told me. “For every violator we identify and prosecute, there are thousands more bad actors who we never know about. So we’ve got to try to get both a fair sentence and the most deterrent value for each case.”

After meeting with Ed Newcomer, Johns became one of Operation High Roller’s strongest supporters. “I thought we should hit this group as hard as we could,” Johns recalled. “We’d never get another chance to get in as deeply as Ed was. They’d be hyper-vigilant about outsiders. But if we took down a large number of targets, we could alter the behavior of pigeon fanciers throughout the country for an entire generation.”

Still, the clock was ticking. Every week more raptors were killed. Newcomer narrowed his focus to the key players.

Navarro, through his position as president of the National Birmingham Roller Club, could encourage the killing of hawks and falcons on a nationwide scale. McGhee seemed to be the Johnny Appleseed of hawk trapping. He once told Newcomer that his trap price of $120 barely covered the cost of materials. He didn’t charge more, he said, because he wanted to “give something back” to his fellow enthusiasts.

To nail McGhee, Newcomer arranged to buy a hawk trap from him in the fall of 2006. In wildlife cases, suspects so often use ignorance as an excuse–I didn’t know it was illegal to kill those hawks–that U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service agents often coax statements of legal awareness out of unwitting suspects. While he and McGhee were loading the trap in a truck, Newcomer saw his opportunity.

“Now, what should I say if some cop finds this trap in my yard?” he asked.

“Don’t tell ’em it’s a hawk trap, whatever you do. Say it’s a cage for your pigeons,” McGhee said. “Since you’re going to have pigeons there in the base, they won’t know any different. Act as dumb as possible.”

“What could happen if they catch me killing hawks?” Newcomer said.

“I imagine there’d be some sort of a fine,” McGhee said. “But it’s almost impossible to get caught.”

Oh, and one more thing, McGhee said. “Don’t ever release a hawk you catch in the trap,” he told Newcomer. Once fooled, a hawk will become twice shy, rendering other pigeon breeders’ traps ineffective.

As he drove away, Ed Newcomer put a mental check mark next to Darik McGhee’s name.

To get hard evidence on Navarro, Newcomer had to get a little dirtier. “Ted” had no easy excuse to visit Navarro’s Los Feliz home. So Newcomer and Sam Jojola staked out Navarro’s backyard from an adjacent drainage ditch. Under cover of darkness, the two agents waded through mud and debris to set up motion-triggered cameras trained on Navarro’s hawk trap.

On their way out, Jojola noticed garbage cans sitting by the curb of Navarro’s street. “Going through trash is one of the best and most under-utilized investigative tools,” Jojola later told me. “It’s a lot of work, though, and there’s a risk of being burned.” (“Burned” is undercover cop talk for getting recognized as a police officer.)

Newcomer and Jojola found nothing but trash and pigeon waste on that first garbage run, but a week later Newcomer and special agent Ho Truong hit pay dirt. At the bottom of Navarro’s can, Truong discovered a dead Cooper’s hawk. The bird, tied up in a white plastic bag, had been beaten to death. The next morning, Newcomer examined the surveillance photos. They showed Navarro, with a wooden stake in his hand, approaching the trapped hawk. The next photo showed an empty, re-baited trap, and Navarro holding a lumpy white plastic bag.

When he’s not tailing suspects, Newcomer can be found exploring Southern California’s secret pockets of wilderness. Los Angeles may be synonymous with urban sprawl, but wild country still fringes the city. Mountain lions, coyotes, deer, bobcats, and gray foxes thrive even in the smaller state parks that pockmark the region. Once, when I talked with him, Newcomer and his wife had just returned from the Carrizo Plain, a little-known national monument about 100 miles north of L.A. It’s a dry, open grassland, and contains spectacular ground cuts, miles long, caused by the San Andreas Fault. “Reminded me a little of southeastern Colorado–pine trees, juniper bushes,” Newcomer said.

Even when he’s off duty, the theme of hidden surveillance never quite goes away. Newcomer’s latest hobby, he told me, is photographing wildlife using camera traps–digital cameras strapped to a tree overnight and triggered by the motion of animals.

“When you hike in the wild places around L.A., you don’t see much wildlife,” Newcomer told me. “There’s so much chaparral that the animals see you before you see them. But there’s plenty out there. I set one out in the Santa Monica Mountains a few months ago and got a great picture of a gray fox staring right at the camera.” He pauses, and then says: “They can smell you on the camera, you know.” Newcomer’s always looking for his own tell, the giveaway, the thing that tips the bad guys to the presence of a cop–even when he’s just stalking foxes for pictures.

In spring 2007, they decided to take down the birds in hand. The rest of the pigeon breeders, they hoped, would get the message: Quit the bird killing, or we’ll come after you. “The big factor was the number of birds being killed,” Hoy later recalled. “We had to stop it.”

Newcomer had seven suspects to serve with search warrants. In Oregon, Hoy had three. Two others were set to be carried out in Texas. All warrants had to be executed almost simultaneously. “As soon as you do the takedown, they’re on the phone to their partners,” Hoy explained. “If you don’t do them at the same time, evidence starts to disappear.”

On May 22, 2007, two dozen law enforcement officers gathered in a conference room to hear Newcomer relate the details of Operation High Roller. The next morning the agents fanned out across Southern California and arrested some of the nation’s leading pigeon breeders.

As the agents carted hawk traps away as evidence, most of the breeders denied harming birds. Juan Navarro said he’d never killed a hawk–but maybe his gardener had. Ed Newcomer personally arrested Keith London, owner of The Pigeon Connection. London never recognized the man cuffing him as the novice known as Ted. Darik McGhee, the trap maker, held fast to the advice he’d given Ted weeks earlier. “Hawk trap?” McGhee told the cops. “What hawk trap? I use that to train my pigeons.”

In the end, Newcomer and other agents arrested all seven breeders. As word of their activities spread, bird conservationists expressed shock at the carnage. “They’re killing a thousand or more birds a year? That number is staggering,” said Bob Sallinger of the Audubon Society of Portland. There are 250 pairs of breeding peregrine falcons in California. On average, each pair rears two chicks to young adulthood. If only one in 10 of the birds killed by the fanciers were peregrines, that means that of the 500 peregrines added to the population each year, more than 100 were subtracted by roller pigeon fanciers.

All of those arrested eventually pled guilty. They received sentences ranging from 1,000 hours of community service and a $3,000 fine for Rayvon Hall to a $25,000 fine for Juan Navarro. In one case, the judge was so outraged by the crimes that he regretted that sentencing guidelines prevented him from giving the defendant jail time.

The arrests shook pigeon culture to its core. Overnight, hawk traps disappeared from roofs and backyards all across America. A schism developed between those defending the accused pigeon fanciers and other, law-abiding pigeon breeders whose concerns over hawk killing had long been ridiculed and shouted down at club meetings. “Unbelievable!” one pigeon breeder wrote in a chat room on roller-pigeon .com. “What the hell were you guys thinking?? This is national, even worldwide and affects every aspect of the sport. Anyone holding office in the NBRC and involved in the hawk sting needs to step down, NOW!!”

Most of those arrested in the case declined to comment for this article. Rayvon Hall didn’t dispute the facts in the case, but he told me that he thought “the government’s response was overkill on this particular subject.” He continues to raise pigeons. “That’s my therapy, my drug,” he said. “I’ll do it until the day I die.”

Anger over the hawk killings, and the lack of jail time for the culprits, led Rep. Peter DeFazio (D-Oregon) to introduce legislation in Congress last November to stiffen penalties for the intentional killing of migratory birds. “I think there should be a bipartisan sense of outrage over this,” DeFazio told The Oregonian. “I don’t know who would apologize for this kind of behavior.”

A few days after the last High Roller defendant was sentenced, Ed Newcomer sat at his desk contemplating his next move. “I’ve got something cooking,” he told me. “Could be nothing, could be something big. Can’t tell you about it yet.”

That afternoon he was going to check out some pigeon breeding websites, see what kind of reaction the latest High Roller sentencing was getting. “There’s a lot of paranoia out there. Some pigeon guys think there’s still an undercover agent working their competitions,” he told me. “They’ll post occasional messages–’Saw another undercover cop at a fly last weekend.’”

“Are there undercover agents still out there?” I asked.

Ed Newcomer leaned back in his chair and smiled. “Who knows?” he said. “Maybe there are.”

Bruce Barcott’s book The Last Flight of the Scarlet Macaw: One Woman’s Fight to Save the World’s Most Beautiful Bird ($26, Random House), was released in February 2008.

First published in 2008; updated December 2021

Credit: Source link