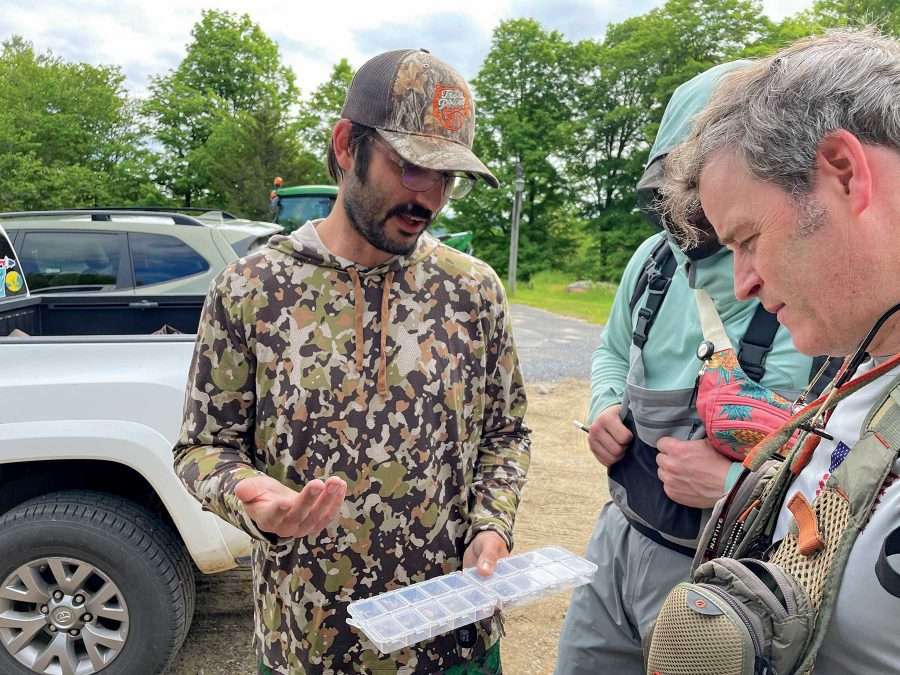

shows off a brook trout

caught near Great Camp

Sagamore in June.

Provided photo by Chris Murphy.

Anglers, researchers team up to preserve one of the region’s few native fish species

By Zachary Matson

Catching a brook trout is one thing. Collecting its DNA is an altogether different challenge. The key is to get a good grip, hold it in a plastic bag filled with water and snip a small piece of its tail fin with sterilized scissors. Stick the clipping in an ethanol-filled vial, tap the vial to make sure it’s there, note your coordinates and pack it away for safekeeping.

“Ok, little guy, you can go back in the water,” Nate Schwarz said upon releasing a squirming seven-incher, minus a tiny piece of fin, in early June.

Schwarz, on his first outing in the Adirondacks, caught four brookies in a few casts. He, Ken Murphy and Bill Beecher collected DNA samples for Trout Power on a stream east of Sagamore Lake.

“You’re contributing to citizen science,” said Murphy, a Utica physician.

Adirondack brook trout, one of the region’s few native fish species, have survived heavy fishing, habitat loss, development, logging, dam construction, the reintroduction of beavers, the spread of non-native game fish, intensive hatchery stocking and widespread acid rain. A major survey of Adirondack lakes estimated that by the end of the 1980s more than 40 lakes had lost entire brook trout populations because of acidification, over 10% of surveyed lakes where brook trout were identified prior to 1970. Scientists now project warming water temperatures could threaten between half and all of the brook trout’s remaining Adirondack habitat without curbs to global carbon emissions.

More to Explore

Subscribe to print/digital issues of Adirondack Explorer,

delivered 7 times a year to your mailbox and/or inbox

Even as the cold-water fish faces the threat of decimation, anglers and researchers are identifying a creel full of likely native strains in the park’s thousands of miles of streams, ponds and lakes. The genetic diversity, more robust than previously understood, could help bolster the species in the face of climate change.

For some anglers, the search for a trophy brook trout has given way to the search for unique brook trout DNA.

Searching for wild strains

Jordan Ross, a fly rod maker near Utica, started Trout Power in 2012 to raise awareness about the negative effects of dams on the West Canada Creek fishery. He hosted fishing tournaments with prizes going to the smallest catch. They were looking for fish smaller than those stocked by the state, evidence the prized fishing area contained wild trout populations.

“We couldn’t find any,” Ross recalled.

The nonprofit organization, incorporated in 2017, expanded its research into the Adirondack Park, shifting focus to native trout genetics. Relying on volunteer anglers and outside researchers, Trout Power collects DNA samples from around the Adirondacks, helping to grow the knowledge of brook trout lineage and distribution. The organization contends it has found previously unidentified native strains of brook trout around Sagamore Lake, in Silver Lake Wilderness and at the headwaters of the Oswegatchie River. The trout they are catching show minimal influence from the strains stocked to supplement recreational fishing.

The organization since 2016 has returned most years to Sagamore Lake and its inlet and outlet streams to collect more DNA. They plan to continue long-term monitoring in the area to track genetic changes.

During an early-June event at Great Camp Sagamore, the group collected more than 60 DNA samples and retrieved temperature loggers positioned throughout the local watershed. Last year, Trout Power conducted a “mission” in the Moose River Plains, hoping to find out whether the range of the Sagamore strain extends to the southwest. “Every time we’ve gone somewhere, we have identified a strain,” said Trout Power President Chris Murphy, a Vermont high school science teacher. “That’s pretty good evidence that there are a lot of these strains out there.”

Studying the genetics

The samples are sent to a lab in Michigan for processing and returned as a string of genomic information. Spencer Bruce, a researcher based at the University at Albany, helps with analysis.

Bruce, whose doctoral research concerned brook trout genetics, confirmed a native strain at Dix Pond and that the strain’s range includes the larger Elk Lake system, connected by East Inlet.

“Future brook trout stocking efforts using hatchery fish in Elk Lake, which may disrupt the genetic integrity of the Dix Pond strain in this water body and elsewhere, should be reconsidered,” Bruce wrote in 2017.

In a large statewide study published in 2019, Bruce and colleagues found that about half of over 80 brook trout populations sampled statewide were genetically unique and many could be unrecorded native strains.

The research compares the genetics of captive strains raised in hatcheries and used in state stocking programs to fish caught in the wild. The more overlap in the DNA, the more genetic mixing between stocked and wild fish. The smaller the overlap, the more likely the fish is part of a pure lineage predating human impact in the region. The fish’s ancestors may have been swimming in the same watershed thousands of years ago.

Bruce’s research confirms some introgression in Adirondack brook trout, the mixing of genes between native and stocked strains, especially in lakes and ponds that have long been the focus of stocking. In the Adirondacks, Bruce found more mixing between native and stocked trout genes than in any other part of the state.

The research also offers a sign that in pockets around the park, especially isolated headwater streams, native fish strains have maintained genetic independence, diversity that could be a powerful hedge against threats to cold-water fish.

The statewide study identified 11 brook trout populations in the Adirondacks with less than 5% genetic material associated with stocked fish—“putatively native” strains. Another 21 Adirondack populations, including the one at Sagamore Lake, showed somewhat higher genetic influence from stocked fish.

“It suggests that the [Sagamore] fish have seen minimal influence from stocked fish, and that in the higher reaches of that watershed there are likely fish that have not been influenced by stocking at all,” Bruce said.

Rivers and salmon series

A series of stories about the effect dams have had on two of the parks’ important rivers, the Boquet and the Saranac.

Dams have changed them, blocking the natural movement of fish for decades.

Managing our heritage

Anglers have long been drawn by the lure and lore of native brook trout.

For more than 60 years, the state has sought to maintain native brook trout lineage in its stocking program. As early as 1954, the state agency used fish pulled from Cranberry Lake to stock St. Regis Pond. Over the years, the state has used large-scale liming or entire kill-offs of non-native fish to restore brook trout populations.

In a 1979 brook trout management plan, DEC aquatic biologist Walter Keller outlined the goal of “preservation of several indigenous strains as a heritage.” The plan listed 11 strains of New York state “heritage” brook trout, including eight Adirondack strains. The heritage strains were centered on ponds and lakes, including Horn Lake, Little Tupper Lake, Nate Pond, Stink Lake and Tamarack Pond. Some of those native strains are still stocked throughout the park, and Keller’s list of heritage strains entered Adirondack mythology as a definitive list of native trout.

Warren County runs one of just three remaining county fish hatcheries in the state, a 38-acre site on the Hudson River in Warrensburg. This summer a heron poached large trout from a demonstration pond open to the public. The county raises domestic brook trout, rainbow trout and Atlantic salmon, as well as nearly 20,000 Horn Lake strain brook trout for DEC.

The fish are raised until they are 18 months old and released in the spring, growing more slowly than the so-called domestic strains developed for hatchery purposes.

Jeff Inglee, the hatchery manager, said the behavioral differences between the Horn Lake strain fish and the domestic fish are obvious. Horn Lake fish act more aggressive and agile when feeding.

“They strike quick and go right back to the bottom,” Inglee said.

The traits appreciated by many anglers are more evident in the native fish as they dart up and down their hatchery raceways. While the domestic hatchery fish are more docile around people, the Horn Lake fish “hate humans,” Inglee said.

For decades the state used hatchery fish to supplement wild populations, but the Department of Environmental Conservation in 2020 shifted its stocking strategy to limit mixing stocked fish with naturally reproducing wild populations. In November 2020, the agency issued a new state trout stream management plan, distinguishing for the first time “wild” streams from stocked ones.

“Anglers drew a sharp distinction between wild and stocked trout fisheries and affirmed that self-sustaining trout have special value,” according to the DEC plan.

The plan called stocking “an inappropriate management strategy” for reaches of small headwater streams in the Adirondacks and Catskills, which are accessed by relatively few anglers, in part because they “constitute a valuable reservoir of native trout biodiversity.”

The plan sought to simplify regulations, while establishing harvest limits for different types of wild stream stretches and to focus stocking where fishing opportunities wouldn’t otherwise exist. It suggests fisheries staff explore the use of sterile hatchery-raised trout as a strategy to prevent mixing in places where wild streams exist near stocked streams.

The state planned to stock nearly 1 million trout in streams statewide this spring, according to a plan published in March.

In the Adirondack Park and surrounding areas, the state planned to stock over 750 miles of stream with over 425,000 hatchery brook trout. Long stretches of the Ausable River remain heavily stocked: DEC planned to stock nearly 40,000 trout along 50 miles of the river’s east and west branches.

While wild fish can show heavy influence from stocked fish, the park’s remaining native strains may hold keys to the species’ long-term protection. The biodiversity offers paths to survive environmental changes, and the different strains can be studied to inform future conservation efforts.

“These populations… represent the last stronghold of wild, native brook trout diversity in the state,” said Jeremy Wright, curator of ichthyology at the New York State Museum and an adviser to Bruce’s research. “The levels of diversity in the Adirondacks is actually heartening. The greater the amount of genetic diversity, the greater the adaptive capability of those different populations.”

Credit: Source link