Just south of the invisible line that divides the Koocanusa reservoir between the U.S. and Canada, Greg Hoffman kneels at the bow of his boat. He slowly draws a long, cone-shaped net up through the water, creating gentle ripples on the otherwise glass-like surface.

It’s mid-October and chilly. Hoffman, a fishery biologist with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, wears a thick grey sweater under his red life jacket and gloves, but these aren’t for warmth. They’re to protect the samples he’s gathering.

Hoffman’s after zooplankton, microscopic animals found in the photic zone — the surface layers of the reservoir illuminated by the sun’s rays.

He carefully pours the contents of the net’s collection cup, including any specimens he’s managed to catch, into a sample bottle for transport to the lab. Anything he can collect will be tested for selenium. The element can be toxic for fish. At high enough concentrations it can lead to deformities, reproductive failure and in a worst-case scenario, population collapse.

The Army Corps has been monitoring water quality in this reservoir since the dam was built but it’s only in more recent years that they’ve started looking closely at selenium.

They’re interested in zooplankton for the simple reason that zooplankton consume algae that may have absorbed selenium from the water — and are then themselves eaten by fish.

“Most of our species in this reservoir are pelagic feeders, the trout and in particular the kokanee, so they’re the ones eating what’s eating the bad stuff,” Hoffman says.

Scientists already know where the selenium is coming from: a string of enormous metallurgical coal mines in B.C.’s Elk Valley.

Parties on all sides, including Teck Resources, which owns the mines, are keen to stem the flow of contamination. But efforts to address pollution soon run up against economic interests — the mines are foundational to the regional economy and big earners for the company. So far, the political will to address the problem has been lacking. The mines are allowed to release selenium at levels well beyond what the province considers safe for aquatic life, and even as experts warn of a growing threat to fish and other aquatic life, regulators are weighing proposals for new coal mines in the valley.

Today, Hoffman and his colleagues are on the frontlines of a watershed-wide data collection effort that’s offering vital insights into the effect of selenium within this complex ecosystem.

“Trying to get our arms around that is tremendously challenging,” he says.

Pollution from the mines has become an increasingly contentious issue between Canada and the United States, where downstream ecosystems, already burdened by human development, are now feeling the added strain of selenium.

The scope of the contamination is extensive. Even a few hundred kilometres downriver, there are fears that increasing selenium pollution threatens the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho’s decades-long effort to restore white sturgeon and burbot populations in the Kootenai River.

“To see any of that work be reversed or effectively cancelled out would be a tragedy to our people and the nature we hold so dear to our hearts,” says Gary Aitken Jr., Kootenai Tribe of Idaho’s vice chair.

Journalists from The Narwhal traced the flow of selenium from the mines down the Fording River, along the Elk, into the Koocanusa reservoir and south across the border until it pours over Montana’s Libby Dam. From there we followed the Kootenai River, which rushes and gurgles before tumbling over the Kootenai Falls on its way to Idaho, where it meanders through farmlands on its way back north, crossing back into B.C. (where the spelling changes from Kootenai to Kootenay) before eventually merging with Kootenay Lake.

At each stop, we found people deeply concerned about the threat selenium poses to fish in these rivers and scientists working hard to understand the consequences of mine pollution as it spreads downstream.

Outside of Elkford, B.C., Wyatt Petryshen stands near the end of the public road leading to Teck’s Fording River Operations. Past a narrow band of trees, he can see the massive terraces of a mine. It’s just a small fraction of the altered landscape. Beyond the rise, the Fording River mining operation is approved to disturb an area larger than 10,000 Canadian football fields.

“It’s hard to comprehend,” he says. “It’s a vast amount of landscape destruction.”

Petryshen is the mining coordinator at the Kootenay-based environmental organization Wildsight, a group that has spent years raising awareness about these vast contamination issues and advocating for stronger government oversight of coal mining in the Elk Valley.

The leftover rock that piles up as mountain tops are stripped to extract coal is the source of one of the major environmental challenges in this region.

The average selenium concentrations detected in eggs during the study was more than double B.C.’s guideline for selenium in fish eggs of 11 micrograms per gram. It was estimated that at those levels detected in the 2012 study, more than 180,000 westslope cutthroat trout fry die from selenium poisoning each year in the Upper Fording River, the report by investigators says.

Teck pleaded guilty last year to contaminating the Fording River in 2012 and was fined $60 million — the largest penalty Canada has ever issued for a Fisheries Act violation.

The company — which in February reported $2.87 billion in 2021 profit attributable to shareholders in its unaudited annual results — has taken steps to address the water pollution stemming from its mines over the years. Teck has so far invested more than $1.2 billion in water treatment and other measures. As of February, the company says it had the capacity to treat 47.5 million litres of water per day in the Elk Valley and plans to increase capacity to 77.5 million litres later this year.

The process hasn’t been without its hurdles. One of Teck’s treatment facilities, for instance, caused a substantial fish kill in 2014 during commissioning. The company states the incident was related to the unintentional release of high levels of ammonia, nitrate, hydrogen sulfide and other contaminants. Teck pled guilty to violating the federal Fisheries Act in 2017 and was ordered to pay a $1.4 million fine.

Chris Stannell, Teck’s public relations manager, says the treatment plants are working and the company expects to see selenium levels further reduced as new facilities start operating.

What remains unclear is the proportion of the mines’ total wastewater Teck is treating. Neither the company nor the provincial government would say.

(The company declined repeated requests for an interview and a tour of its water treatment facilities, but provided written responses to emailed questions.)

In order to safeguard aquatic life, B.C.’s water quality guidelines recommend selenium levels not exceed two parts per billion. Those same guidelines limit selenium in drinking water to 10 parts per billion in order to safeguard for human health.

The limit outlined in Teck’s permit was also exceeded in October, November and December of 2020, when selenium levels averaged 112 parts per billion, 102.5 parts per billion and 124 parts per billion, respectively.

For years there were fears that the selenium pollution would eventually prove too much for the genetically distinct population of westslope cutthroat trout found in the Upper Fording River.

Then, just a couple years ago, Teck reported a 93 per cent decline in the adult westslope cutthroat trout numbers.

A team of 18 expert consultants Teck hired to investigate hypothesized the collapse was caused by the combination of “extreme ice conditions” and “sparse overwintering habitats and restrictive fish passage conditions during the preceding migration period.”

Water quality issues, Stannell says, were not found to be a primary factor.

But they can’t “be ruled out as a contributor to the decline,” the consultant report says. “If fish are stressed due to the quality of the water, they may be more susceptible to other stressors.”

The Fording merges with the Elk River south of Elkford, B.C. From there, the water meanders through forests and farmland on its way to Fernie.

Anglers travel from all over the world to fish this river.

The fish are beautiful and there are a lot of them, says Andres Gonzalez, a longtime guide.

Standing on the rocky shoreline, Gonzalez casts a line out into the swiftly moving river. It’s late afternoon and the sun is hanging low above the rocky mountains, already dusted with snow.

Within minutes his line goes taut. He pulls back, reeling in his catch: a westslope cutthroat trout.

This portion of the Elk is a catch and release river, but before Gonzalez lets this fish go, he inserts a tag at the base of its dorsal fin using a thick injection needle. He scans the tag, snaps a photo of the fish, logs its location and gently lets it swim back out into the river.

“It’s in really good shape,” he says.

Gonzalez is one of the anglers working with Nupqu, a First Nations-owned, natural resource management consulting firm, and the Ministry of Forests on a fish tagging pilot project to help estimate westslope cutthroat trout population numbers.

Establishing a benchmark will make it easier to set population targets and measure changes in fish numbers.

“Sometimes you hear the old-timers say, no, it’s kind of blown out … but I put 90 days in the water every season, even more, and there’s lots of fish there,” Gonzalez says.

On occasion, he does come by fish with missing gill plates, he says. Though Gonzalez says it’s possible some of that damage is from fishing, it’s also a classic sign of selenium poisoning.

For Gonzalez, the selenium pollution from the mines is a source of concern — his livelihood depends on the health of the river, the health of the fish.

But at the same time, he sees Teck and its mines as part of the valley, where friends and neighbours earn their own livings.

The company is one of the largest employers in the area, with some 4,800 people employed across its Elk Valley operations, including 335 in environmental roles, in 2020, according to Stannell.

“Our people live and work in the Elk Valley region — they care deeply about ensuring the environment is protected,” he says.

At this point, what Gonzalez wants is more data about the fish and the water quality.

“There’s a lack of information and you cannot manage something without proper information,” he says.

What data is available, though, shows selenium levels in the Elk River are rising.

About 50 kilometres south of Fernie, the Elk splits and braids before it flows into the Koocanusa reservoir — the flooded stretch of Kootenay River above Montana’s Libby Dam, where selenium concentrations are also trending up.

Here too, selenium levels tested last year ranged from more than 1.5 to almost five times higher than B.C.’s guidelines.

For thousands of years these rivers have carried spiritual and cultural significance for the Yaq̓it ʔa·knuqⱡi ‘it, one of several Ktunaxa Nation communities.

They not only provided food, water and a way of travel. The Kootenay is also central to the Ktunaxa creation story, Nasuʔkin (Chief) Heidi Gravelle says.

“Water is so essential to life: it’s got its physical, mental, emotional, spiritual aspects to it that are key to all living things,” she says.

On this crisp October morning, Gravelle is sitting inside the boardroom at the Yaq̓it ʔa·knuqⱡi ‘it offices in Grasmere, B.C., not far from the U.S. border. A black bear pelt hangs on the wall behind her. Outside, the community is blanketed by a thick, lingering fog.

“Prior to the mines, people could drink out of the rivers,” she says. But not anymore.

While people still fish for pleasure, “nobody will eat fish out of there because of the contaminants, which is sad,” she says. “That was a huge part of our history.”

Gravelle says fish populations have dropped over the last decade.

“The mines have put some work into fixing the selenium problem,” she says. “But it’s not enough.”

She wants the provincial government to address the gaps in existing legislation and regulations that have allowed this contamination issue to persist.

“There needs to be stronger environmental regulations at the end of the day, and accountability — so raise the bar and if you don’t meet it, you’re done,” she says.

Despite Teck’s repeated water pollution infractions, it has continually been allowed to expand its Elk Valley coal mines and is once again pitching a major new undertaking with its Fording River expansion project. The company says the new mine is needed to ensure the existing 1,400 jobs at its Fording River mine are maintained for the next several decades.

Teck’s coal mines are seen as the Elk Valley’s economic engine, contributing an estimated $4.6 billion to B.C.’s gross domestic product through salaries, spending on supplies and local services, and the knock-on effect of spending by Teck’s employees, according to a recent report produced for the BC Chamber of Commerce.

Gravelle says she understands the economic value of the mines for the region, “but at what cost? Where’s the line? And, who draws that line?”

“At the end of the day, what is a win? Shut it all down and get our land back to the way it was,” she says. “I’ll never see that. I don’t know if my children will ever see that, and that’s heartbreaking.”

And, even if mining were to stop today, “we’re no better off than we are right now,” Gravelle says.

Selenium could continue to leach from existing waste rock piles for centuries and with several new projects proposed, there are fears throughout the watershed that the pollution will get worse.

“Both Teck and our government take the concerns of the Ktunaxa as well as people on the other side of the border and nations on the other side of the border seriously,” B.C. Environment and Climate Change Strategy Minister George Heyman says in an interview in November.

The province is committed to working with the Ktunaxa Nation “to reach a resolution in which the Ktunaxa believe correctly that their interests and their future have been addressed,” he says

“It’s important to resolve this.”

The Koocanusa reservoir, a vast human-made lake spanning the international boundary, collects water from both the Kootenay and Elk Rivers.

For years, a joint B.C.-Montana working group involving experts, representatives from Indigenous governments, Teck and multiple state and provincial government agencies, has been monitoring and researching selenium contamination in the reservoir.

The hope was that the B.C. and Montana governments would adopt a single selenium standard for Koocanusa.

After years of work, Montana moved forward on its own.

The state officially adopted the more stringent selenium standard for Koocanusa of 0.8 parts per billion in February 2021 after securing approval from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

But for months, it was “pretty much crickets from north of the border,” says Sexton, who has worked with the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes on this issue for more than a decade.

“Meanwhile, the data show that the contaminant trends just continue to increase,” she says.

Teck, which isn’t subject to Montana’s rules, is fighting the state’s new standard.

A lawyer for the company recently filed an expansive Freedom of information request for public records, data and emails from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency related to Teck Resources and selenium levels in Lake Koocanusa or the Kootenai River since 2015. The request also specifically asks for communications between the agency and the B.C. government, the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho, the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, the Ktunaxa Nation, and a number of environmental organizations on those same topics.

Teck’s lawyers argued in a petition to Montana’s Board of Environmental Review, that the new standard “was designed to, has been used to, and does target Teck.” In its latest Annual Information Form, the company makes it clear that the limit “may not be achievable with existing technology.”

In November, B.C.’s environment ministry confirmed to The Narwhal that it’s considering a new water quality objective of 0.85 parts per billion for the Canadian side of the Koocanusa reservoir. That figure will be released for public consultation before it’s confirmed, but once it’s established it will form the basis for coming amendments to Teck’s Elk Valley Water Quality Plan.

The updated plan will, in turn, inform adjustments to Teck’s permit, which include the only B.C. standards Teck is legally required to meet.

A spokesperson for the environment ministry said the public consultation period for the water quality objective is expected later this spring. But it remains unclear how long it will take for more stringent standards to come in place.

In the meantime, there’s evidence that selenium is already bioaccumulating, or building up through the food chain, at existing concentrations, according to a joint 2020 letter by Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes and the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho.

“Once it’s contaminated, it’s very difficult to clean and it’s very difficult to hold the mining companies accountable,” says Richard Janssen, and Qlispe Tribal Member of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes.

The Tribes aren’t against all mining, he says, but they are opposed to mining that threatens their water, fish and wildlife.

“Our people are going to be here forever,” he says. “I’m just here to protect the resource during my time and for the next seven generations.”

The Ktunaxa Nation Council, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes and the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho are all part of the broader Ktunaxa Nation, whose traditional territory covers parts of the region known today as B.C., Alberta, Montana, Idaho and Washington State.

While the impacts of selenium and other contaminants from the mines are a significant concern throughout the Kootenai River watershed, for the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, Lake Koocanusa and the Kootenai River downstream of the Libby Dam, are a particular focus.

“My people still go up there, sometimes on a monthly basis,” Janssen says.

“If those benefits that we’ve enjoyed for thousands of years are no longer safe to eat, that’s a concern,” he says. “That’s the big one, the cultural impacts.”

Sexton, who represents the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes alongside Janssen on the B.C.-Montana working group, says she has no doubt after sitting through a decade of meetings with Teck staff, that the company wants to address the pollution issues.

“But whether or not it’s possible to address the problem and expand your footprint at the same time, I think is a really critical question,” she says. Especially when scientists are still trying to understand the repercussions of the existing pollution.

One thing is sure — there are no quick fixes. The selenium contamination may have been created over more than a century of mining, but without intervention, the problem could persist for much longer than that, says Travis Schmidt, a United States Geological Survey research ecologist, who is leading the agency’s Lake Koocanusa monitoring project.

For as long as the piles of waste rock are weathered and worn by the elements, selenium could continue to seep into nearby rivers and creeks before flowing downstream.

It’s mid-October and the late afternoon sun shines brightly as Schmidt and Chad Reese, the team’s field crew lead, motor out across the Koocanusa reservoir.

Reese pulls the boat up alongside a pontoon that’s anchored just above the Libby Dam, an immense concrete structure completed in the 1970s. They step onto the small floating platform next to a bright yellow contraption adorned with solar panels.

An unassuming gray cooler — the super sipper — sits next to it.

Below the cooler, hidden from view, fixed lines extend to different depths in the reservoir. Each day, the super sipper takes a small drink of water through these straw-like lines, collecting them into weekly samples that offer insight into the selenium concentrations at different depths.

This is one of three United States Geological Survey automatic water quality stations monitoring selenium concentrations and other parametres in the Koocanusa reservoir. The others are stationed just south of the international boundary — the closest the team can get from the U.S. side to the source of the selenium — and in the Kootenai River just below the dam.

Data collected last year at the team’s international boundary site shows selenium levels ranged between one and two parts per billion — above Montana’s new 0.8 parts per billion standard.

While available data shows selenium inputs to Lake Koocanusa are rising, Schmidt and other researchers are still working to understand what exactly that means for the reservoir as a whole. Are levels rising more in some areas than others? How is it affecting fish, birds and other wildlife? And what are the consequences for the river ecosystem downstream of the dam?

One of the difficulties in trying to understand the impacts of selenium levels in Koocanusa is the complex hydrology of the reservoir itself, Schmidt says.

Schmidt says it’s possible that Koocanusa may act variably as a sink as well as a source of selenium. The reservoir, he explains, could be absorbing the contaminant in its sediments, where anaerobic microbes can transform it. If that’s the case, the question is how long is the selenium being stored in sediments? And how long before it’s released back into the water, free to flow downstream?

At this point, the idea of Koocanusa as a bioreactor is still a hypothesis, Schmidt says. More detailed studies are needed to understand what exactly happens to the selenium that comes into the reservoir from the Elk River before it’s carried over the Libby Dam, down the 129-metre concrete wall and into the Kootenai River, where the United States Geological Survey recorded selenium levels ranging from 0.87 parts per billion to 1.4 parts per billion last year.

For the ecosystems downstream and the communities who depend on them the results will matter deeply.

Just downstream of the dam, sits Dave Blackburn’s Kootenai Angler, a business Blackburn built up slowly over the course of decades. He started as a lone fly fishing guide in 1982 and today runs a small tackle shop, restaurant, cabins and leads a team of guides.

“My whole life has revolved around the river, I raised my family here,” Blackburn says, sitting by the warm woodstove in his quiet restaurant one October morning.

“It’s a real special place to me.”

Selenium isn’t the only threat Blackburn and his “business partners” — the rainbow trout that frequent this stretch of Kootenai River — have faced, but “it’s the scariest thing that I’ve seen come along in years,” he says.

He pulls out his phone and searches back through his photos for a particular shot of a rainbow trout. He points to its damaged gill plate — “nobody can prove that’s selenium damage, but that’s a sign,” he says.

Over the last three years, Blackburn estimates he’s seen about 10 fish with similar damage.

“They are a very resilient fish, but they’re not resilient to high levels of selenium,” he says.

From the beginning, a key flaw with the B.C.-Montana working group, Sexton says, was its limited focus on the effects of selenium in Lake Koocanusa, when the contamination extends well beyond the dam.

Some 90 kilometres downriver, across the state line, the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho has pressing concerns about the threat selenium poses to endangered white sturgeon and burbot populations.

These fish hold spiritual and cultural significance for the tribe, says Aitken Jr., Kootenai Tribe of Idaho vice-chair.

They “hold their own places in our traditions, but they also helped sustain us through harsh winters,” he says in an email to The Narwhal. “The sweet white meat was a welcome treat for hungry bands with rapidly declining stores.”

They’re also “a tribal success story that our members can be proud of,” he says.

The Kootenai Tribe of Idaho has been working for more than three decades to restore white sturgeon and almost 20 years to rebuild burbot populations, species that may have been wiped out long ago from the Kootenai River if not for the tribe’s conservation aquaculture program.

At its Twin Rivers Hatchery, near the confluence of the Moyie and Kootenai Rivers, tiny prehistoric-looking sturgeon swim slowly along the bottom of large, round tanks.

Not long ago, their mothers — enormous fish that reach two to 2.5 metres on the Kootenai — were in similar tanks, positioned upside down in the water as hatchery staff pushed along their undersides to release their eggs.

Once fertilized with milt from the male fish, the eggs become adhesive, which in nature allows them to stick to rocks or crevices, Kevin James, the hatchery’s assistant manager explains.

In the hatchery, that adhesiveness can cause the eggs to clump together, risking suffocation, so, staff gently stir the eggs with a feather, mixing in a fine polishing agent to help keep them separated.

The eggs are then transferred to shallower, rectangular tanks, where a constant flow of water keeps them rolling until the fish are ready to hatch.

About six weeks after hatching, half the fish from each family group are moved to larger tanks in the next room over.

Here, juvenile sturgeon, still smaller than James’ hand, are swimming, flexing their bodies back and forth to move through the water.

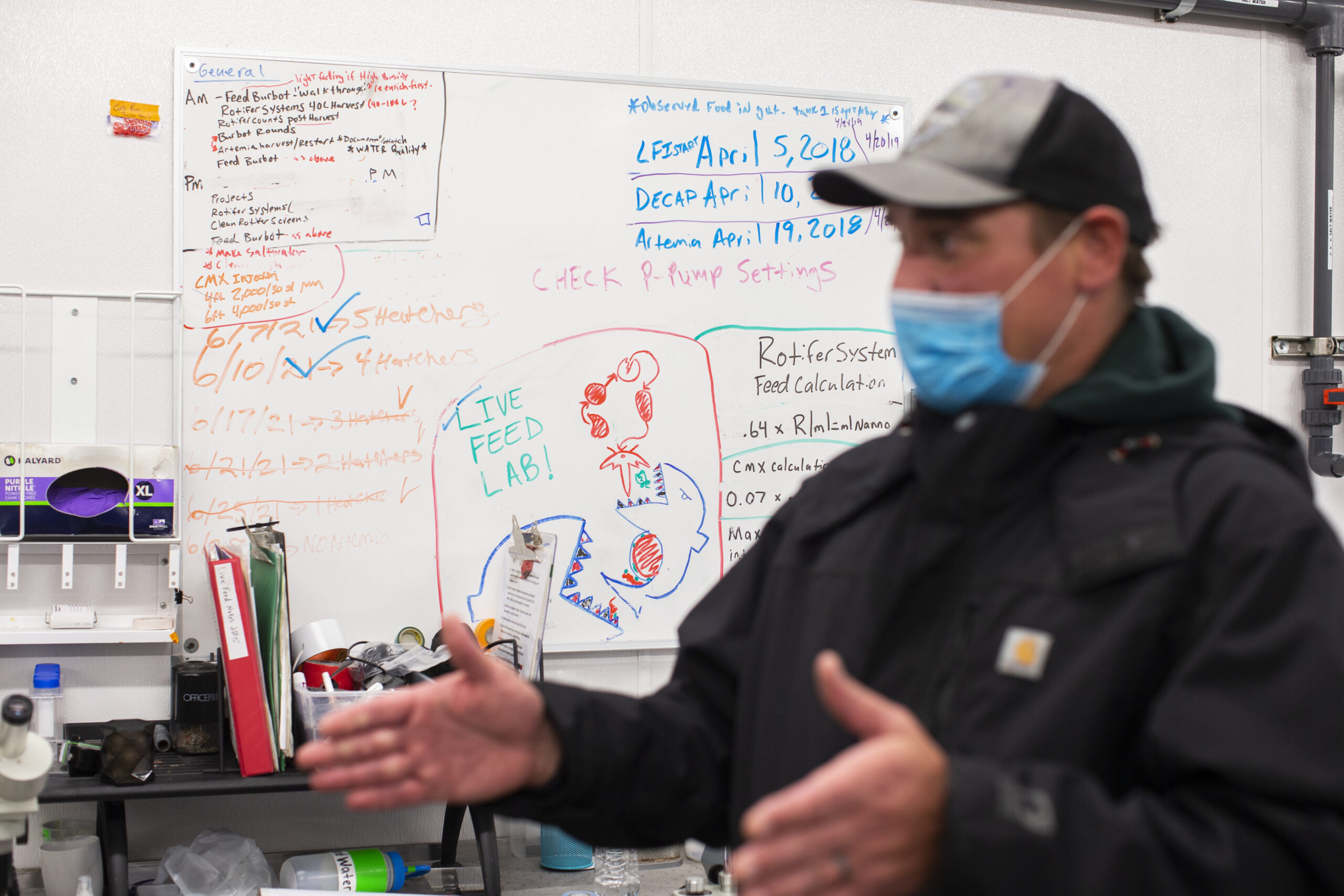

Through another door and another boot wash station, a biosecurity measure, is a whole separate set-up devoted to spawning and rearing burbot, which unlike sturgeon, require live prey.

The hatchery team keep a steady flow of zooplankton and artemia, a brine shrimp, pumped into the burbot tanks so there’s food waiting whenever the young fish are ready to eat.

Otherwise, they turn on each other, says Nathan Jensen, who supervises the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho’s conservation aquaculture program.

Jensen says the hatchery programs have been “very successful as far as perpetuating the burbot and sturgeon populations in this basin.”

Some of the first sturgeon released from the tribe’s hatchery are now reaching their late twenties and early thirties — reproductive age for a fish that can live to be more than 100 years old. Burbot, meanwhile, which were almost extirpated from the river at the turn of the century, are now being seen in numbers large enough to support both a subsistence and a sport fishery.

But neither sturgeon nor burbot are close to self-sustaining — the Tribe’s ultimate goal.

One hurdle is that the river itself isn’t very biologically productive, meaning there likely isn’t enough of the right kind of food to support fish hatched in the wild, says Sue Ireland, the Kootenai Tribe’s longtime fish and wildlife director, who recently retired.

Diking and agricultural development severed the main stem of the river from vital wetland habitat long ago.

The Libby Dam brought even more challenging conditions to bear. Alongside massive fluctuations in water levels and temperature, it restricted the flow of nutrients.

The massive concrete wall is essentially a trap for sediments and other materials that contain the basic building blocks of an ecosystem — nutrients like phosphorous that foster the growth of algae and other plant life.

Over the years, the Kootenai Tribe of Idaho and the Army Corps of Engineers have worked together to manage water flows to limit the impact on the downstream ecosystem. The Tribe has also been adding liquid phosphorous to the water since 2005 to help bolster the growth of algae and aquatic insects that fish, such as rainbow trout, rely on for food.

At the same time, they have been working to restore fish habitat along the Kootenai River, by planting riparian vegetation, creating pools for spawning fish and reconnecting productive wetland areas that offer rearing habitat and more nutritious food for growing fish.

The hope was that eventually the habitat would be able to support self-sustaining fish populations. The fear today is that as some of these more productive habitats are reconnected to the river, it’s creating the perfect conditions for microbes to create more toxic forms of selenium.

“It’s a sucker punch after all this,” Ireland says.

As part of its water sampling program along the Kootenai River, the Kootenai Tribe has collected samples from a wetland area that’s intermittently connected to the river, a wetland area that’s slated for reconnection and another that’s offsite.

Preliminary data seems to indicate that selenium is being transformed into those more concerning, more bioavailable forms in the wetland area that’s sometimes connected to the Kootenai River, particularly during peak summer months, Genny Hoyle, the tribe’s aquatic biologist, says.

Total selenium levels, which measure all forms of the element in the water column, in this stretch of the Kootenai range from 0.8 to 1.2 parts per billion — below the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s selenium standard for flowing water of 3.1 parts per billion. But even at those levels, a segment of the river has already been listed as impaired for selenium because the concentrations of the contaminant in some mountain whitefish eggs are already higher than the Environmental Protection Agency’s criteria for fish egg-ovary tissue.

“Burbot are higher than they ought to be” as well, says Shawn Young, a fish and aquatic biologist with the Kootenai Tribe, who recently took over as the fish and wildlife director.

Of 35 female burbot sampled in 2020 and 2021, two exceeded the Environmental Protection Agency standard for selenium in fish egg-ovary tissue. Eight others were “approaching exceedance,” Young says.

The two fish with the highest selenium concentrations had been released from the hatchery as juvenilles into the wetland habitat that was intermittently reconnected to the main stem of the Kootenai River through a habitat restoration project. They were also the youngest fish tested. Others with high concentrations were released into the lower river itself. The fish with some of the lowest selenium burdens, meanwhile, were released further downstream in Kootenay Lake.

“It looks like the younger fish may be experiencing a higher selenium environment and they’re bioaccumulating it quickly, right from early life,” Young says, at a virtual briefing on the tribe’s latest sampling data in February.

The Kootenai Tribe has tested eggs from sturgeon captured and spawned for their hatchery program, and so far, none have exceeded the EPA standard for egg-ovary tissue. But Young says they are seeing a rising trend in selenium levels in sturgeon as well, with the highest levels detected in 2021.

Back at the hatchery in mid-October, Young says studies of other fish species have shown there’s reason to be concerned about the selenium concentrations they’re detecting in burbot and sturgeon.

“The levels we’re seeing have been confirmed to have negative impacts for reproduction, for growth, for outright mortality,” he says.

Addressing the risks to sturgeon “and all species in the territory is a high priority for our people in keeping our covenant with the creator,” Aitken Jr. says.

Eventually, Hoyle says, she hopes to see a site specific selenium standard established for the Kootenai River downstream of Libby Dam, one that’s more protective of the fish populations the tribe is working so hard to protect and rebuild.

The challenge is that it’s governments north of the border that have authority over the source of the contamination — the coal mines back in Canada.

A spokesperson for B.C.’s Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy said in a statement that the ministry has learned a lot about how selenium bioaccumulates.

Teck continues to make adjustments to its water treatment plants and other water quality measures to “manage this risk,” the statement says. And, the company is required to monitor and study selenium speciation in the environment.

“Teck is committed to taking the steps necessary to address this challenge and to ensure the watershed is maintained for future generations,” Stannell, Teck’s spokesperson, says of the pollution issues.

Yet, despite the company’s investments in water treatment and research, selenium continues to be a concern and with several new mines proposed, there’s a growing urgency to address it.

The Kootenai Tribe of Idaho, the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes and the Ktunaxa Nation, have for years called for this pollution issue to be referred to the International Joint Commission, a body created under the Boundary Waters Treaty signed by Canada and the U.S. in 1909.

One of the commission’s main roles is investigating and recommending solutions to transboundary water disputes and many observers see it as the natural venue to hash out a solution to this ongoing pollution problem.

The Kootenai Tribe of Idaho, Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes and Ktunaxa Nation have sent repeated letters to federal government officials in Washington and Ottawa asking for the issue to be referred to the joint commission or for some other transboundary framework to be established that gives the Tribal and First Nation governments as well as all other affected jurisdictions equal standing — something the B.C.-Montana working group failed to do.

“What hasn’t taken place yet in this whole watershed is a fair and equitable process and that is basically what the tribal government letters have asked for,” Sexton says.

A spokesperson for Canada’s federal government said in a statement that the government “is aware of calls for an [International Joint Commission] reference on this issue, and is working closely with the province of British Columbia, Indigenous nations and U.S. counterparts to ensure that appropriate actions are taken to protect the environment.”

Neither B.C. Environment Minister Heyman nor the federal spokesperson would say whether their governments support calls for an International Joint Commission reference.

Last summer, the Ktunaxa Nation asked the B.C. and federal environment ministers to suspend all environmental assessments for new coal mines in the Elk Valley.

“We will no longer accept the ‘business as usual’ approach to coal mining,” the Ktunaxa Nation Council’s letter says.

“Ktunaxa laws and customs require us to act as stewards of our our ʔamak ȼ wuʔu [land and water], so that they will continue to support a healthy and thriving Ktunaxa community and culture for seven generations into the future,” it continues.

“Unfortunately, a legacy of major coal mines in Qukin ʔamakʔis, approved without our consent, now threatens our ability to uphold our responsibilities as Indigenous title holders and caretakers of this area within ʔamakʔis Ktunaxa.”

In an interview, B.C. Minister Heyman says there’s still a long way to go before the proposed mining projects could be approved or permitted, given that they are all in early stages of the environmental assessment process.

“For people who say there should be nothing until this issue is resolved, that is in fact how the process works,” he says. “Nothing’s been decided.”

Sexton, however, says “we’re having the wrong conversation in this watershed right now.”

After more than a century of mining in the Elk Valley, the focus shouldn’t be on expanding mining, it should be on understanding the effects and extent of existing pollution and the accountability for those impacts, she says.

“Of course, from our perspective, we need measures that will be successful in meeting the water quality objective,” Heyman says. “That’s what I believe all parties are focused on.”

“While some of the measures Teck put in place were not successful, it is not like they did not take measures to address the problem, or that they are not continuing to take measures,” he adds.

Despite those efforts, selenium continues to leach from the piles of waste rock that have built up over more than a century of mining. It continues to flow from the Fording River, into the Elk and south through Koocanusa. It pours over the Libby Dam into the Kootenai River, where it cuts through mountain valleys and rushes over the Kootenai Falls. It meanders through canyons and farmland in Idaho on its way back to the B.C., where it empties into Kootenay Lake — far west of where it first drains into the rivers of the Elk Valley.

Credit: Source link