Halls of fame don’t always recognize the right things, sometimes overlooking the subtle achievements, the victories over the hidden adversities, the odds-defying rise to competitiveness when starting from absolutely nothing.

There’s no Hall of Coaching Impact, no way to gauge the percentage of players on a team whose personal benefits from the experience alter their lifelong well-being.

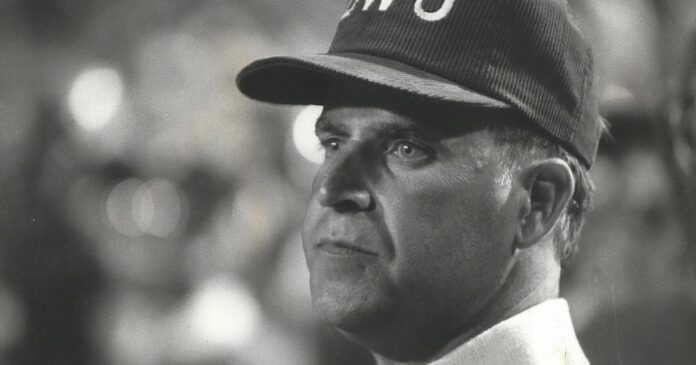

But the Inland Northwest Sports Hall of Fame got it right in the case of Dick Zornes, one of the new inductees this week. Observers close to Zornes doubt that any coach in the country won more games with fewer resources, and few had a more profound effect on their players’ lives after football.

Those Eastern Washington University football alums certainly came away with enough stories to carry them for years, stories about Zornes’ football acumen, his native intelligence, his frugality mandated by circumstances, his loyalty, and his toughness, his toughness – oh, my goodness – his toughness.

•••

Dick Zornes didn’t want the EWU job, turning it down the first time it was offered. He had played there, as a four-year starter and two-year captain while getting an honors degree in pre-med/biology (3.7 GPA) in the 1960s. He played for coach/mentor Dave Holmes, and later assisted him, taking on his old-school, accountability-based coaching style.

Zornes put those lessons to effect at Columbia Basin College, being voted to a national junior college championship in 1978, his second year as head coach. Zornes’ team went undefeated, limiting opponents to 43 points in 10 games.

EWU president George Frederickson offered him promises of a rising program, and after initial skepticism, Zornes took the chance in 1979. He was allowed one assistant, Larry Hattemer, and was allotted 20 “tuition” scholarships – not full rides, only tuition.

“We started with nothing,” Zornes said. “I had a pipeline to some JC kids and it was pretty much coach ‘Hat’ and me the first year.”

The Eagles stepped up from Division II to I-AA Independent in 1984 and joined the Big Sky Conference in 1987.

“By ’84, ’85, ’86, we were pretty damned good,” Zornes said. “There was a time where I thought we were going to really be something, maybe even a Boise State. We were up to 63 scholarships and I had five assistants, and, boom, we took a major budget cut, from 63 scholarships to 42, and we couldn’t recruit for three years.”

Zornes’ battles were not just the opponents on an upgraded schedule, but an annual exhausting and frustrating struggle for the program’s survival.

“In ’89, they asked me to be athletic director and I told them I would if we did certain things, and we got back on top again and won the (Big Sky) conference in ’92.”

Between coaching and the AD duties, he worked 365 days a year and “it burned me up.” He retired from coaching in 1993 with a record of 89-66-2, having earned Big Sky Coach of the Year honors in 1992.

•••

“My idea of two-a-days now is making the decision whether to golf in the morning or go fishing, and then do the other one in the afternoon,” Zornes said.

He and his wife Heidi still ski, too, and hit the gym three or four times a week.

And, yes, he still lifts weights. Anyone near the Zornes program has stories of his capacity to get the attention of his athletes by joining them in the weight room.

“He would walk by and challenge you,” said Tommy Williams, an All-America defensive end on the 1992 team. “He’d look at what you were lifting and say, ‘You think that’s enough? Put another plate on there and get out of the way.’ Then he’d get down there and start repping with 315 or more. I mean, I don’t know how old he was at the time, but it was freakish.”

Still is.

“I got my shoulder replaced seven or eight years ago, so I just kind of do reps now, not much more than 145-150 pounds,” he said. “It’s kind of kiddie lifting.”

Kiddie lifting? The man is 78 years old.

•••

How small was the EWU recruiting budget? The Eagles didn’t actually have one. Mike Kramer, an assistant who replaced Zornes as head coach in 1994, tells a story that not only captures the impecunious state of Eagles football, but also the humility of Zornes as the head coach.

On trips to find prospects on the West Side of the state, Zornes and four assistants would get a cheap room in Renton. Room – singular. The four assistants would double-up on the beds and Zornes “would grab a comforter and curl up on the floor,” Kramer said.

Wait, the head coach slept on the floor? “Yep, every time,” Kramer said.

Jim McElwain, who played for Zornes and also assisted him before moving on to assistantships at powerhouses like Alabama, Michigan, etc., and head positions at Florida, Colorado State and now Central Michigan, confirmed the Zornes-on-the-floor story, and remembers a horrifying moment as a young assistant.

“One time I got up in the middle of the night and I ended up kicking him,” McElwain said. “I looked down and it was coach Zornes. I thought, ‘Oh, man, this isn’t going to go well.’ ”

Zornes thought nothing of the sleeping arrangements. “It was OK. It was who we were and what we did.”

University budget woes almost cost them a game in 1982. Athletic director Ron Raver came into Zornes’ office with news of an immediately mandated, campus-wide budget cut, threatening the trip to Northern Arizona.

Zornes argued that the money for the plane tickets and bus rental were already spent and tallied against the budget, so he promised to cancel the hotel rooms and raise money to pay for the meals to help save the game.

“We got up at 5 (Saturday) morning, flew to Phoenix, got on the bus, drove up to Flagstaff, checked into a day room that would fit 45 guys on chairs, ate a pregame meal the boosters paid for,” Zornes said. “We went out and beat NAU (14-7), bussed back down to Phoenix, and every kid found a place to bed down in the airport until we got on the flight and flew home.”

One-day turnaround. No hotel. A memorable road win.

Of course, every opponent could use the stories of impending default against Zornes and his staff. It forced them to work harder and smarter, and turn over every stone searching for talent others might have missed.

“We got into every high school in the state, no high school was too small. We recruited a lot of kids that nobody else recruited, so Eastern was a good deal for them,” Zornes said. “Gradually, we built a rapport with the kids we had and they told other kids this was a pretty good situation.”

Zornes had something else working for him, an uncanny insight into human potential. Kramer saw it time after time. “He could see what was inside them,” Kramer said. “To a greater extent than I could imagine, he was able to take a guy and develop him. He could force guys into becoming something they never knew they had in them.”

•••

Zornes’ former assistants look back wistfully at the hard times, which now sound like stories from the Great Depression.

“To be honest, I was really fortunate to have some really good assistants,” Zornes said. “Most of the guys stuck with me, and staff stability is so important. I felt bad none of them ever made any money, but I think their experience with me was OK.”

Hard times produced memorable lessons.

“He took a bunch of us he didn’t pay any money to and taught us how to coach,” McElwain said. “You did what you had to do to help the place, and no task was too small. That’s what made it great … sweeping up the locker room, helping with laundry, selling popcorn at concession stands during a basketball game. Whatever it took.”

McElwain assisted big-named coaches in the NFL and top college programs, most notably serving on Nick Saban staffs for two Alabama national championship teams.

“I’ve been so fortunate, with the stops along the way, and I owe it all to (Zornes),” McElwain said. “I truly believe he is so underappreciated as a coach. I would have loved to have seen him have an opportunity at one of these programs because I know how successful they would have been with his leadership. He was that good.”

McElwain sounded a bit emotional remembering “one of my great moments.” It wasn’t a national championship or a big coaching contract, but having the chance to impress Zornes.

Some friends brought Zornes down to Alabama when McElwain was coordinating the offense. “He sat down in my office and started looking at the game plan, and I was so nervous. He’s one of those guys you want to spend your life trying to make him proud. For him to be there and meet coach Saban …”

Saban saw how much Zornes meant to McElwain. “Coach Saban said to me, ‘That guy must have had a helluva impact on you. I could tell you were nervous introducing him to me, and you were so on-point when you were around him.’ ”

Kramer said Zornes left his assistants with a winning blueprint to follow, rooted in the respect he earned from the players. “He was so intelligent he would have been successful doing anything, a doctor, an air force pilot. Coaching? If you consider the amount of resources Dick had, I don’t think there’s another coach in America who could have done the same thing.”

•••

Transfer Tommy Williams was intimidated by Zornes when he first arrived in Cheney after growing up in Chicago.

“He was brilliant, but his delivery could be a little harsh,” said Williams, now coaching at North Central High and operating a nonprofit community outreach program in Spokane. “I always say he could snatch your heart out in practice, but he would give it back to you before you left the field. He would explain why he was hard on you so you learned from it. Everybody who played for him would run through a brick wall for him because that was the kind of man he was.”

Williams remembered watching a big lineman starting a fight in practice, and seeing Zornes race across the field and break it up by taking the brawler down like a steer wrestler. “Everybody was shocked to see how he could subdue that guy.”

The further Williams gets from his playing days, the more he feels Zornes’ influence in other ways. “As a father, as a husband, the way he treated his wife and kids and grandkids, I wanted to emulate that. That’s the big thing; it has nothing to do with football.”

•••

“To be honest with you, I’ve had a smile on my face since I heard about this (Hall of Fame recognition),” Zornes said, fresh off an afternoon fly fishing at Waitts Lake. “I’m pretty excited about it.”

Told that players and former assistants spoke at length about his impact on their lives, and how deserving he was of this honor, Zornes responded like a person realizing he had accomplished his mission.

“I hope that’s true,” he said. “That’s what I wanted to have happen. That’s how I came out of my football experience with Dave Holmes; I was a better person, I had a better chance of being a good husband, a good father, a good football coach because of the experience I had with him. Those are the things I hoped would happen.”

Kramer granted that “we didn’t always have a winning season, but it was an exquisite pleasure to have worked for him. There is only one Dick Zornes.”

Now, decades later, McElwain said he relies on lessons from Zornes every day. “I think about all the lives he’s touched,” he said. “The guys I played with, the players I coached when he was head coach. There’s one common denominator to the success any of us have had, and that’s Dick Zornes.”

Which is exactly the kind of legacy that deserves to be honored by a hall of fame.

Credit: Source link