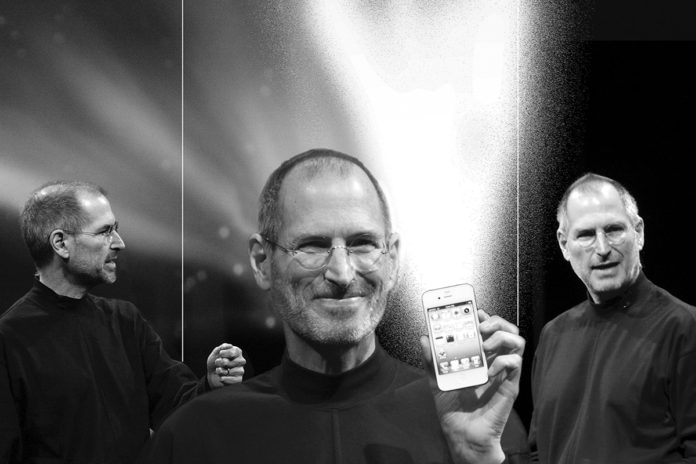

Steve Jobs died ten years ago this month. At the corporate memorial held on Apple’s campus, a previously unreleased version of the 1997 “Think Different” Apple commercial was played. In this version, Jobs himself performed the voice-over, so everyone at the memorial heard him speak one final exhortation to the world: “The people who are crazy enough to think they can change the world are the ones who do.”

Jobs was certain of many things: Apple products should be closed systems that exclude other products in order to maximize user experience. Black turtlenecks are the one and only shirt to be worn. On-off switches are ugly. And the work that he was doing with Apple was changing the world for the better.

In 1982, when Apple was a budding computer company, Jobs gave a speech to the Academy of Achievement. In this speech, he described how supposedly ordinary things such as going to college or believing in God inhibited innovation and stifled change. He told the audience that if they could move beyond the ordinary, they could have the capacity to change the world.

One of the things that I had in my mind growing up—I don’t know how it got there—was that the world was sort of something that happened just outside your peepers, and you didn’t really try to change it. You just sorta tried to find your place in it and have the best life you could, and it would all just go on out there—and there were some pretty bright people running it. And, as you start to interact with some of these people, you find they’re not a lot different than you. . . . They might have a little more judgment in some areas, but basically they’re the same. And, once you realize that, you start to feel you have a responsibility to do something about it, because the world’s in pretty bad shape right now.

Jobs continued his speech by saying that the most ecstatic thing a person can do in life is “put something back into that pool”—into civilization. Jobs advocated changing the world by contributing something new and meaningful to it. Human beings, according to Jobs, have a responsibility to be guardians of the earth for future generations, to pay attention to problems and do something about them.

In 1983, Jobs recruited John Sculley, then president of Pepsi-Co, to become chief executive officer of Apple by asking him a provocative question: “Do you want to spend the rest of your life selling sugared water, or do you want a chance to change the world?”

Though he was certain of this calling, Jobs was less certain where it came from. He had a persistent uncertainty when it came to God. According to his biographer Walter Isaacson, near the time of his death, Jobs said, “I’m about fifty-fifty on believing in God. For most of my life, I’ve felt that there must be more to our existence than meets the eye.”

Waffling on God, however, did not mean that Jobs entirely rejected religion. He had a keen interest in Hinduism and Zen Buddhism. Zen in particular influenced Jobs’s penchant for minimalism and his appreciation for intuition, both of which are apparent in his product design.

Jobs had strong, largely negative thoughts about Christianity, which he saw as having crystallized in an unhealthy form. According to Jobs, “the juice goes out of Christianity when it becomes too based on faith rather than on living like Jesus or seeing the world as Jesus saw it.” For Jobs, dogma and doctrine were religious ossifications stifling innovation and different ways of thinking.

His incredulity toward the Christian faith began at a young age. According to Isaacson, Jobs was deeply troubled by a Life magazine cover showing two starving children in Biafra. This prompted him to ask his pastor why God permits such suffering, and he was not satisfied by the pastor’s response. This led him to the conclusion that Christianity was unable to ameliorate the problems of this world. While only a teenager, Jobs vowed that he was done with both the God of Christianity and the church.

Instead of Christianity or even religion more broadly, Jobs saw technology and his work with Apple as having the potential to create a better future for the world. He applied himself fully to this end.

This raises a simple question: Did it work?

Was Jobs right to dismiss Christianity and its supposedly ordinary belief in God that inhibits innovation? Did his intuition serve him well when he set out on the path to change the world by giving us the iPhone, iPad, and MacBook?

The answer depends on what metric one uses. From a purely economic perspective, Jobs was very successful. At various times in its corporate history, Apple has had more cash on hand than the US Treasury. From a design or user-experience perspective, Jobs liberated the world from clunky interfaces and unusable technologies.

From an ecological perspective, however, the 12th iteration of the iPhone and the hurried pace of planned obsolescence have been an environmental tragedy. According to a 2019 United Nations report, the world produces 50 million tons of electronic waste per year, and only 20 percent of this e-waste is recycled. By 2050, global e-waste could reach 120 million tons per year. While Jobs and Apple are not the only forces behind this e-waste, they are culpable in it because of their endless innovation and production. Innovation in and of itself is an environmental disaster.

The demand for phone and laptop batteries has fueled frenetic cobalt mining in African countries such as the Democratic Republic of the Congo. While concern for Africa led Jobs to depart from the Christian faith and the church, his inventions have led to dangerous mining practices and child labor in Africa. From an international development perspective, Jobs failed to ameliorate the woes of children in Africa that once troubled him so deeply.

Beyond ecology and international development, contemporary philosophy raises its own concerns about the legacy of Steve Jobs. Modern scholars of nihilism and technology such as Arthur Kroker and Nolen Gertz have argued that modern gadgetry and technological devices have harmed humanity. Drawing on the work of Friedrich Nietzsche and his philosophy of nihilism, these scholars suggest that tech innovators like Jobs have helped make the sick sicker by bringing about something worse than religion.

What do they mean? Isaacson suggests that Nietzsche and Jobs share much in common. Both were brash, unapologetic, and independent thinkers. In The Will to Technology and the Culture of Nihilism, Kroker describes Nietzsche this way: “Literally fast-forwarded by his consciousness of the nervous system of power, Nietzsche’s body was burned up by thought.” In many ways, these words hold true for Jobs as well. Both died young—Nietzsche at 55 and Jobs at 56—yet they crammed enough accomplishments into a short lifetime to be remembered by history. Both had an interest in Eastern religion, and both were formed by Christianity and ultimately took issue with it.

Nietzsche and Jobs both possessed indomitable wills. As described in Isaacon’s biography, Jobs is known for his “reality distortion field,” his unique ability to bend both reality and the will of others to accord with his own. Jobs’s RDF resembles Nietzsche’s central idea of the will to power: power is good, weakness is bad, and happiness is the increase of power and overcoming resistance.

Nevertheless, despite all that these two held in common, Nietzsche would have detested the world that Jobs helped to create. Had Nietzsche been around to assess the legacy of Jobs, he would likely have made a brash pronouncement upon it: He made the sick sicker.

In On the Genealogy of Morality, Nietzsche argues that Christianity won out in the historical struggle between competing moral value systems. Concepts like good, evil, guilt, and sin thus became taken for granted in society. Nietzsche claims that the Christian faith supplied people with a will and value system—”moral eugenics,” as Kroker calls it—along with multiple remedies for when the will goes awry. He argues that these values turned everything upside down by making the strong weak and the weak strong.

In Nihilism and Technology, Gertz describes how Nietzsche understood the Christian moral world to be “a sick world, a world where we are sick of being mortal, sick of being human, and sick of being ourselves.” Nietzsche held that the religious ideals of Christianity were life destroying and world destroying because they encouraged individuals to be will-less, passively waiting to be defined by someone else’s values. According to Gertz, Nietzsche disdained the “ascetic priests” because they “sought to soothe rather than cure our suffering, prescribing to us . . . ways to rechannel our instincts, such as self-hypnosis, mechanical activity, petty pleasures, herd instinct, and orgies of feeling.”

According to Gertz, the problem is that Jobs took up the work of Nietzsche’s ascetic priests: he supplied people with wants, values, and remedies. Rejecting the idea that customers know what they want or need, Jobs preferred to create a desire within consumers. (“People don’t know what they want until you show it to them. That’s why I never rely on market research. Our task is to read things that are not yet on the page.”) Jobs worked to create products—remedies, cures, or medications—so compelling that consumers simply had to have them. The rapturous attention that consumers devote to Apple launch events is evidence of his success.

The devices and gadgets that Jobs helped create encourage users to be will-less, to allow someone else to impose their values on them. This is, according to Nietzsche, a way to avoid being human.

The problems that Nietzsche identified in the Christian faith are being reproduced by the tech companies of today. Kroker puts this in a radical way: “Perhaps the will to Christianity and digitality were always flip sides of the same historical movement, that Christianity was always a sustained period of moral preparation for the coming to be of the digital nerve? Today, the mask of Christianity is removed, only to reveal the triumph of the digital gods.”

Apple Watches, iPhones, and other devices reshape our values, invite us to take things for granted, and effortlessly consume the medications prescribed by tech companies. The Apple Watch even tells you when to do biological tasks such as breathing or walking. iPhones and iPads, with their responsive touch screens and dazzling pixels, provide us with all that we need for self-hypnosis. These devices are an effortless means of mechanically consuming digital content in what Gertz calls “orgies of clicking.” Apple’s Siri was the first digital assistant waiting at our beck and call to dispense answers, tell us what to do, and help us avoid the essential human chore of having to think.

To be certain, Jobs and Apple are not alone in creating the nihilistic world of modern technology. Netflix, Google, Facebook, and other tech companies also leave humanity sick, distracted, and in a state of perpetual techno-hypnosis. However, it is indisputable that Jobs was on the vanguard of these emerging technologies and tech companies. Scholars of nihilism and technology provide compelling reasons to think that tech innovators like Jobs have helped bring about something worse than the religion that he rejected. It may be that Jobs became so enamored by the pursuit of innovation, beautiful design, and exceptional user experience that he failed to consider why, when, and how these are worth pursuing.

If it’s true that technological devices have made the sick sicker, then how might the sick be made well? In this world of gadgets, is there hope for healing and living again as humans?

In Technology and the Character of Contemporary Life, Albert Borgmann argues that technology has shaped contemporary life around its peculiar pattern. Like Kroker and Gertz, Borgmann claims that the peculiar pattern of modern technology is fatally debilitating for human flourishing. He suggests that the pattern of technology becomes particularly harmful when there are no means by which one can “prune back the excesses of technology and restrict it to a supporting role.”

The pruning is found, according to Borgmann, in “focal things.” A focal thing is a locus for physical engagement, social relations, and experiences that happen in and around this thing. Examples of focal things are violins and fly-fishing rods. While iPhones make no demand on our skills or strength, violins and fly rods do. A focal thing is a concrete, tangible, and engaging thing that requires a practice to prosper within: “It sponsors discipline and skill which are exercised in a unity of achievement and enjoyment, of mind, body, and the world, of myself and others, and in a social union.”

Contra Nietzsche and Jobs, Borgmann proposes that the Christian faith can be a fulcrum of change for reforming technology and contemporary life. For example, Borgmann sees the Eucharist as being a focal thing: participating in it is a tangible and engaging practice that requires knowledge, practice, attention, and social unity. Like a family gathering around the dinner table without their iPhones, the church’s gathering around the Lord’s table is a sacred practice that is regularly reenacted. Borgmann argues that this focal practice has the power to be a centering and orienting force within a technological society. The Lord’s Supper helps us live as humans in a world of gadgets and devices.

Christianity can further challenge modern technology by making room for communal celebration. “We must make a clearing for the celebration of the Word of God,” says Borgmann. “Christians must meet the rule of technology with a deliberate and regular counterpractice.” By taking up things like violins and fly rods or partaking of the Lord’s Supper and the communal celebration of worship, healing can come to those who are sick, distracted, and in a state of perpetual techno-hypnosis.

In his famous 2005 Stanford commencement address, Jobs said, “You can’t connect the dots looking forward; you can only connect them looking backward. So, you have to trust that the dots will somehow connect in your future. You have to trust in something—your gut, destiny, life, karma, whatever.”

When 2031 arrives and it is time to mark the 20th anniversary of Jobs’s death, there will be more dots to connect. The passage of time will enable us to make even better sense of the technological world that Jobs helped make. Perhaps it will become clearer that he helped to make the sick sicker. Perhaps it will become clear that he helped make the world—and us—better. Or perhaps there will be some new thinker crazy enough to set out to change the world.

A version of this article appears in the print edition under the title “Gods of tech.”

Credit: Source link