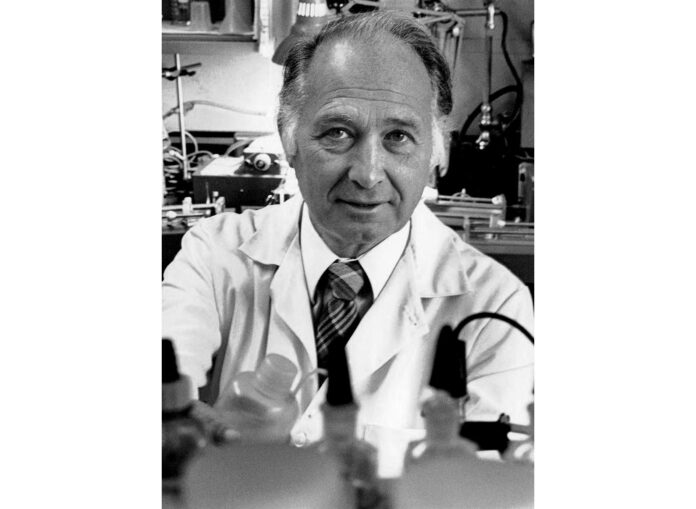

Gerold Grodsky was not a physician and not a diabetic. But he understood how insulin worked as well as any doctor who treated the chronic disease and any patient who tried to stabilize their blood sugar.

Grodsky was a research scientist at UCSF who developed a means of accurately measuring the level of insulin in the body. This discovery, published in a 1960 paper, was life changing for the population of insulin-dependent, or Type 1 diabetics, and the much larger population of insulin-resistant Type 2 diabetics.

“Jerry is a legend,” said Aaron Kowalski, CEO of the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, the global organization for Type 1 research and advocacy in New York City. “He was critical in our understanding of how the body makes insulin and how to better use it.”

Grodsky was foundational to the metabolic research unit at UCSF, which became the UCSF Diabetes Center, a world-renowned facility that celebrated its 20th anniversary last November. Grodsky attended an entire day of anniversary events followed by a long dinner that evening.

“At the end, he came up to me and said what an incredible day it was,” said Dr. Mark Anderson who now chairs the Diabetes Center. “The glass was always half full with Jerry.”

That was Grodsky’s last public appearance. He died Dec. 29 in the hospital after spending his final years in a penthouse apartment on the Embarcadero with a panoramic view of the Bay Bridge. He was 95.

Grodsky leaves behind a legacy that includes the faculty position of Gerold Grodsky Ph.D. Chair in Diabetes Research at UCSF and the Gerold and Kayla Grodsky Award in Basic Research, issued to the most prominent research scientist in the field worldwide.

“He loved the science of Type 1 diabetes research and stayed on top of the next generation of scientists who are moving research forward,” said Kowalski. “His discoveries really led to more modernized insulin therapy regimens.”

Gerold Morton Grodsky was born Jan. 18, 1927 in St. Louis, Mo. His father, Louis Grodsky, owned a soft drink company. Jerry, as he was known, and his younger brother, Myron, worked at the family business, Kenwood Club Bottling Co., where their father created the formula for KayC Root Beer, a local favorite in Illinois and Missouri.

“Part of the family lore was developing recipes,” said his daughter, Andrea Huber. “Louis was also trying to find a recipe for hot chocolate without the skin on top. All of this led to my dad’s fascination with chemical experimentation.”

At the University of Illinois in Champaign, he joined the V-12 Naval Officer Training Program and somehow found time to be head cheerleader for the Fighting Illini. He graduated Summa Cum Laude in chemistry at the same time he made ensign in the U.S. Navy. He continued on for a masters in biochemistry, then came to UC Berkeley to pursue his Ph.D.

On the steps of the International House, he met Kayla Wolfe, an art student at UC Berkeley. They were married in 1952 and a daughter, Andrea, was born a year later. After earning his Ph.D., he moved the family to England where Grodsky did post-doctoral study at Cambridge University in a lab that was doing some of the earliest work with the insulin molecule.

Upon his return to the United States, the family decided to settle in San Francisco and he took a job at the chemical department of Sherwin-Williams, the paint company, working there just long enough to know he did not want to stay in private industry. In the mid-1950s, he joined the Metabolic Research Unit at UCSF and began his life’s work studying insulin.

Insulin, the hormone produced in the pancreas to break down carbohydrates into blood sugar, was discovered by Dr. Frederick Banting and a team of researchers at the University of Toronto in 1921. Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease that destroys the insulin-producing cells in the pancreas.

“Type 1 diabetes is 100% fatal without insulin,” said Kowalksi of the JDRF. In order to survive, a diabetic must know what their blood sugar level is and stabilize it by injecting insulin.

In the early years of treatment, urine tests were the only way to measure blood sugar levels, and the race was on among scientists to find a better way. Both the means of measuring blood sugar and the insulin used to treat it were primitive when Grodsky started his research.

“There was an ‘aha moment’ every time there was a breakthrough with one of his experiments,” said Huber. One of these moments was the discovery of a connection between obesity and Type 2 diabetes, made when Grodsky was still in his 30s. Probably the biggest aha moment was in his development of a technique to measure the secretion of insulin from the pancreas. This enabled scientists to eventually work out a combination of fast- and slow-releasing insulin that allows a diabetic to stabilize blood sugar.

Grodsky’s research unit at UCSF included 11 full-time scientists, technicians and professors who were augmented by fellows who came from around the world to work on the research side of diabetes. Openings in his lab were in high demand.

“Jerry looked for enthusiastic and creative people,” said Teri Elander, who was the lab administrator. “There was a lot of enjoyment and laughter. Jerry did not take anything too seriously except for science and fly fishing.”

Grodsky’s group often worked together with a clinical lab run by endocrinologist Dr. John Karam. In 1963 they teamed up as the “first to link obesity to Type 2 diabetes, resulting in revolutionary changes in diabetes treatment and prevention,” noted in a 2014 article in UCSF Magazine that marked the top scientific discoveries in 150 years at the university, going all the way back to 1864.

After his initial breakthroughs in the early 1960s, Grodsky put in another 33 years before retiring from his position as a professor of biochemistry and closed his lab in the metabolic research unit. But that retirement was a technicality. He lectured in more than 25 countries and continued attending seminars and staying on top of diabetes research.

“His influence on diabetes research was well beyond his immediate contributions because he had such a positive influence on everyone around him,” said Anderson, of the UCSF Diabetes Center.

Grodsky and his wife, Kayla, raised two daughters, Andrea and Jamie, on Washington Street in Presidio Heights. Kayla Grodsky died at age 73, in 2003, and Jamie Grodsky, who became a law professor at George Washington University in Washington, D.C. died in 2010, at age 54.

In 2004, when Grodsky was 74, he met Roberta Sherman and they spent nearly 20 years together, traveling the world.

“It was a bonus relationship that neither one of us expected to have,” said Sherman. “It was the best 20 years of both of our lives.” But he kept his own apartment and never missed his monthly poker games, five hours each sitting on average. He won money in October and broke even in November. He missed the December game.

He and his brother Myron stayed as close as they had been as kids at the family bottling plant, and Myron would come out from St. Louis to sail under the Golden Gate Bridge aboard Grodsky’s cabin cruiser. Myron died in 2020.

“Jerry had charisma and charm,” said Prisella Grodsky, Myron’s wife. Every August, even at 95, he took a fishing trip to Alaska. In October, 2022 he chaired a session at an international diabetes conference. To the end he had great empathy for all diabetics.

“There is a tremendous bond that Type 1 people have in terms of managing this disease,” said Kowalski, a Type 1 diabetic himself.

“It is incredible when people like Jerry come along and fit in, even though he was not Type 1 and was not personally affected by it. He was a class act, Jerry. I will miss him.”

Sam Whiting is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: swhiting@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @SamWhitingSF

Credit: Source link