Remembering the late poet through his writing about fishing on his beloved river

“The Tobacco Tin Jewel Box”

In winter on the river, July, August, when it was blowing a gale and raining, the fishermen would sit at the bar in The Angler’s Rest and look out at the trees bending on the mountain behind The Gut. Old Dutch, Dutchy Kerslake’s dad, Moose, Phil, Bigfoot and old Fa Fa, my grandfather – they’d sit there drinking beers with rum chasers, and tell stories and complain about the weather. Back in those days, the money paid by the co-op for a big jewfish, a 60 to 70 pounder, could feed a family for a week. Catches of these great fish weren’t rare, but they didn’t happen on a regular basis. A month could pass between catches; other times there’d be four or five caught in a matter of weeks. The professionals have always caught more jewfish on lines than nets; in fact, it’s a very rare thing to get one in the nets, the big fish usually go straight through the fine mesh, especially in those days before nylon.

Jewfish are beautiful looking creatures, kings of the river, and after World War Two the fisheries officially renamed them “mulloway” and they are sold under that name, but most fisherman just call them “jew” or “jewies”. They say the first name for them was “jewel fish”, because if you split the head apart in behind the eyes there sits, like a third eye, a little pearl-like bone like a gland in front of the brain. Mulloway can grow up to seven feet and can weigh up to 150 pounds. Usually, the big ones are between 60 and 80 pounds. The bigger the fish, the bigger the “jewel”, and these are beautiful things, like a real pearl: irregular, round and sometimes tear-shaped, they shine with an opalescent glow in sunlight. The jewels aren’t worth taking unless the fish is at least 40 pounds.

In the winter as it blew a gale the old codgers remembered the great fish in their lives and discussed the ways they had been caught. All the top men carried old tobacco tins – Golden Flake, Woodbine – and these tins had beautiful designs painted on the lids. Each fisherman had his tin and some carried them around for years; some had been handed down by their fathers. Inside these tins they carried their “jewels”. When a drunken discussion started to go on the turn, before fists were thrown, some old bloke would just reach into his coat and take out the tin. With a movement resembling some strange ritual, the arm stretched out and the gnarled, black freckled hand placed a tin on the bar. Then the old codger would say in a loud voice as he thumped the bar: “Right!” Things were sorted out, whose fish was bigger in the winter of ’42 or whatever. Old Dutch or Fa Fa. Out came the tobacco tins. Silence.

What a wonderful picture, these old gentlemen of the river, all opening their lids and carefully holding their “jewels” in sometimes very trembling hands. They placed them on the bar, then the one with the largest jewel would put it back and break the silence by rattling his tin in front of the others, shaking it like a gambler shakes dice, muttering his charm or curse.

Then the barman would start pulling beers. They all had to buy the winner a middy each. Ten or so beers. Old Fa Fa would chuckle at the thought – the night was his.

“Hawkesbury Bream: The Lighter Side”

It’s six in the morning, the tide is full and the water surface of the bay I’m fishing is glass. The line flicks off my little Mitchell. Fine as a strand of silk it travels across the top of the water. I click back the bail and lift the rod sideways. A bream bucks under and the line cuts through the water. With the 2-kilo Maxima pulling out from the reel’s ultra-smooth drag and my sanded-down Ugly Stik cushioning the bream’s struggle, I guide it in carefully through the mangrove roots to my net.

On days like this, when everything works out perfectly and you are casting into the Hawkesbury mangroves on light tackle for bream, all the trouble and care you have put into your preparation is more than worth it. I have been fishing the Hawkesbury for 30 years now and still find this type of fishing one of the most rewarding experiences you can have. But to make it work and to catch fish a lot of thought and planning must go into it.

I can still remember the first fish I caught on the Hawkesbury, on school holidays when I was about 10, from the public wharf at Brooklyn. In those days I was used to catching yellowtail and slimy mackerel on handlines from the wharves at Balmoral and The Spit, with long-shank hooks and no lead. Well, I tried the same at Brooklyn. I remember not being able to see through the muddy water and thinking I didn’t have much of a chance; it was so different to the clear water and sand at Balmoral. I couldn’t believe it when my line shot off under the wharf and I hooked into a big bream. From that day on I returned again and again, each time discovering more about Hawkesbury bream.

These days with our sophisticated high-tech tackle, super lures and wonder wobblers, we often overlook some of the most effective and the most pleasurable skills of fishing. My approach is to copy nature as much as possible, to pay great attention to bait and the way it is presented. I remember my grandfather, a fisherman who lived on the river until he was 98, telling me he would never offer a fish something he wouldn’t eat himself. Natural bait presented in the most natural way; light lines with no lead or as little lead as possible, so the bait floats rather than sits on the bottom in the mud.

When I fish the river, I find a likely looking bay, not too wide, with oyster leases and mangroves. There are some bays on the river with little waterfalls at the top, usually between valleys. These are top spots for bream. I try to use whatever the fish are feeding on. Around Mooney and at Parsley Bay there are yabbies, small crabs, nippers and soldier crabs. The yabbies are always around the edges of sandy spits and the green nippers you can find under rocks are better bait for bream than anything else. Local prawns are good, but they must be fresh, preferably live. Sometimes you can buy live prawns at the fishermen’s co-op at Brooklyn.

In writing this I notice that my approach to bream fishing has gone in a great circle and now I’m back to a method not too far removed from the way I caught my first Hawkesbury bream. I went through times of mixing up some powerful and at times very strange pudding recipes. Then I started using bass plugs, then fishing the channels with heavy lead with long leaders and French hooks. Now I’m sure the secret is natural bait and ultra-light tackle, sometimes a kilo or less. The main problem with light gear on the river is the Hawkesbury’s powerful tides. The way to fish is just one hour either side of the tide in the deep water or around the shallow bays near the oyster leases. I find the hour at the top of the tide most productive especially when it coincides with dawn or dusk.

One perfect morning it was high tide at 6am and not a big tide, around 1.3 metres which is a good breaming tide. I had collected bait from the same bay the day before, small crabs and green nippers. There was no wind at all so I was able to use 1-kilo line. I use Maxima, for its softness and translucency, a little Mitchell 4430 Z reel coupled with a 7-foot Ugly Stik rod that I have built up for bream. I sanded the blank back towards the butt so it makes a soft cast with the unweighted crab or nippers. I watched my bait fly out, the mono sailing its arc like a spiderweb. Almost as soon as the kicking nipper floated to the bottom, whack! The line tightened on the surface, then went down in a solid rod-bending hook-up. Breambo!

Within an hour I had four beautiful bream in my keeper net, all big dark-gold river fish, along with four school jews. Mulloway are also very keen on a live nipper presented to them on a floating light line. When I’m asked how I went last time I fished the river, I get some very strange looks when I reply, “Not bad, but the bloody jewies were thicker than catfish!” It’s not far from the truth. Sometimes small jew (soapies) and not so small jew can be a problem when fishing for bream.

Catfish are usually the plague fish of the Hawkesbury, especially on big tides in summer, but when fishing a floating bait they’re not a problem, being bottom-feeders. When fishing for bream this way, I keep the bait moving. I usually cast out, let the bait half sink then move it in about half a metre at a time. I’ve often been smashed up by some monster bream almost on the surface. It’s almost like fly fishing with bait.

Another “problem” can be flathead. With such light line any decent lizard cuts itself off in the first couple of head shakes, but I don’t let anything distract me. When you decide to fish for bream it’s best to stick to it and not start chopping and changing rigs as soon as something else busts you up.

Another important factor in breaming the Hawkesbury is berley. I use wheat soaked all night with a dash of tuna oil and a fillet of minced mullet mixed up with a bit of sand. Only use berley a half hour either side of the tide and just a handful every five minutes.

One of the most deadly berley mixes is soldier crabs chopped up and mixed with sand. I’ve found this mix especially good when fishing the road bridge in a boat. The best bream spot around the bridge is three main pylons back from the Newcastle end and about four boat lengths out from the bridge. Cast in close towards the pylons.

I only fish the road bridge on small tides and usually find the first hour of the run-in best. The tide stops for about half an hour at the bottom of the tide and this is when the best bream are caught. Again, it works best with light line and no lead. If you can manage to get some live prawns and swim them off towards the pylons on light line you’ll find yourself pulling in bream as big as snapper. If you pick a low that corresponds with either dawn or dusk any time of the year you can’t go wrong.

One time the best bream, just under 2 kilos, was not caught by me on 1-kilo line with a live nipper, but by my son Orlando. Orlando was fishing for mulloway, with a whole squid on ganged 2/0 hooks, when this classic Hawkesbury mega-bream decided it would prove there’s an exception to every rule!

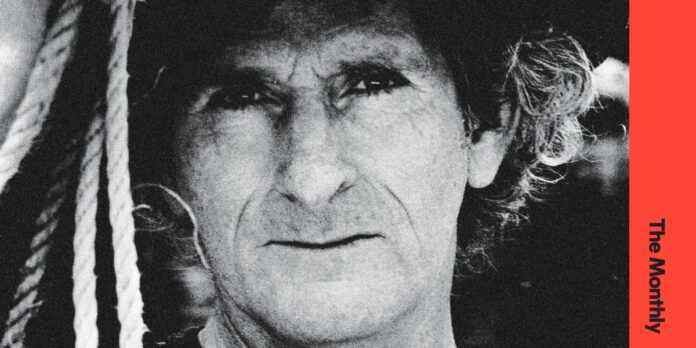

Acclaimed poet, publisher and memoirist Robert Adamson died in December 2022. He fished the Hawkesbury for more than 50 years.“The Tobacco Tin Jewel Box” was first published in Fishing World, August 1997, and “Hawkesbury Bream: The Lighter Side” was first published in Fishing World, April 1989.

Credit: Source link