I stood on the bridge over Punch Brook, watching a small barefoot boy who had fallen asleep in the sun, his line still in the water. There was a school of brook trout just below me, and I wondered why they were not enticed by the boy’s offering.

You can’t really say where Punch Brook begins. At some point a collection of rivulets from the swamp out in Salisbury or down a gully on Smith Hill road all converge and collect into a respectable enough body of water for trout to call it home, and always has it been so. This stream and other braided courses caress paths through the bedrock down to the mighty Merrimack, the river whose death Thoreau lamented and eulogized with a call to bombing the dams which even now both strangle and protect.

Here the water yet runs free, although closely downstream there are the remains of a mill, both friend and foe of the fish I sought as the spring rains receded and the Salvelinus appeared in the clearing water as a painting appears from an artist’s palette, conjured from a random mélange of color to a finished masterpiece. All trickery of light and illusion as they appeared and disappeared from view, little white fins anchoring them in your disbelief and rendering them from imagination to the material.

The granite upstream from the bridge had trails worn into it long before the audacity of the colonies sought to ensnare this land, and I have walked up them, each step in the green gloaming taking me farther from the here-to-day, from my troubles and passions, to a time and a place where we belonged to the land and not elsewise. In short distance, the moss under your feet is finer than the most expensive Persian rugs, and whole worlds exist within its green chatoyancy, should you but kneel to it, and lay your head along it, letting the mysteries we so easily pass unfold. Armies of British Soldiers stand at salute ignored by the civilizations that move amongst them. I have lain there whole afternoons lost in their reverie.

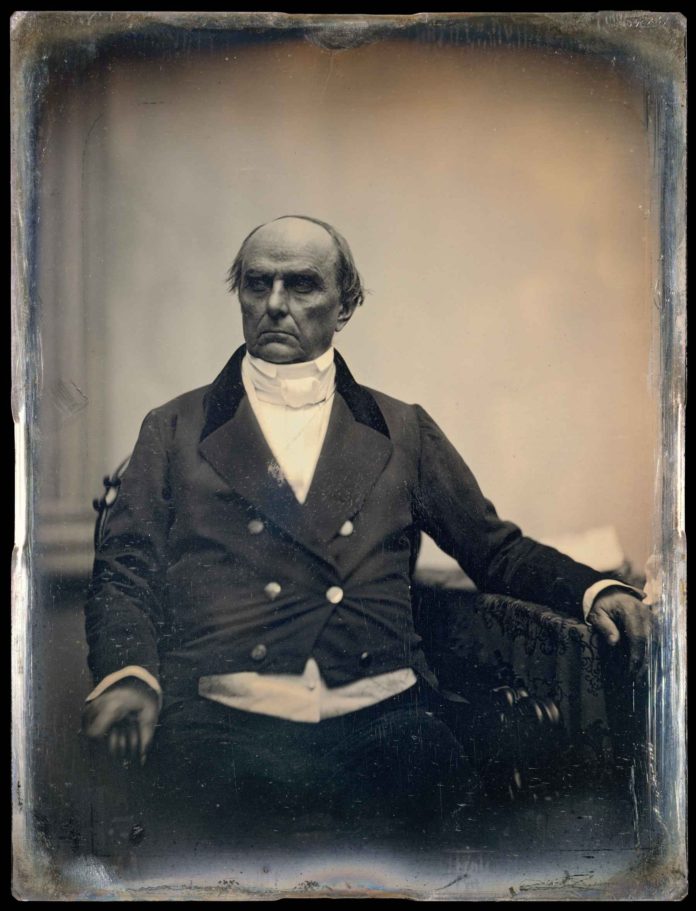

It was a fine spring day, and I was lost between the poles of such enigmas – celebrating this moment and yet seeing it caught in the web of time, pulled hither and yon by the deeds of men – when Daniel Webster rode up on his big grey. I only knew him by reputation and lithographed likeness, but the cliff-high brow and anthracite eyes did give him away. I nodded to him but he ignored me as he dismounted, and taking a rod from the saddle made his roundabout way through the bushes to the pool upstream of the bridge. The water burbled slightly, but the breeze was upon my face and we were not twenty paces apart when he stopped. He seemed surprised by the boy, who sat up when Dan’l appeared.

“Do I intrude?”

The boy laughed, or not; perhaps it was just the stream I heard on the wind.

“As soon as I catch dinner, I have to go back to my chores,” said the boy reeling up his line.

Dan’l looked down at him, “Well then, shall you not hurry?”

“I do admit, I find the fishing preferable to the catching, as each fish brings me closer to going home.”

“Ah,” said Dan’l, “as finely argued as any case I have brought before the court.” He gestured to the pool. “Would you mind? I too am on my way home, and much as I miss it, I do miss this brook somewhat more and would pause here for the moment.”

“Don’t mind.”

“I’ve never seen you here before, how long you been coming here?”

“Oh, most likely reckon, couple hundred years or so.”

Dan’l chuckled. “Couple hundred years. I like that.” He spit on a knot and tightened it and looked down at the water playing in the stones at his feet. “I know what you mean though, feels like a least a hundred years myself.”

“I heard you once caught a monster trout down New York way.”

“Ah, the ‘Trial of Lives’ at Fireplace Mills, an apt name, I fear, for the place I may have earned my way to hell.” The boy tilted his head, and Dan’l explained. “I do not think God forgives leaving his sermons, even to catch one-stone trout.”

“One stone,” and a whistle, “why would god make such a fish if he didn’t want you to catch it? Seems like it was for the Glory of God for sure.”

“A temptation, indeed.” He looked over at the boy. “Witnessed by the priest, the Mayor of New York, a future president, and half the county. But that was not the foulness of the deed. They carried me home drunk the night before, and drunk even in church I was. Meanwhile a slave waited up all night to spot that fish, and then came to get me out of church. A church that would not let me out nor let him in. Does history know his name? I do not. No, this was for the glory of man, one man. Even I can’t argue that one away.”

“Is there any ground whose fruit was not once watered in blood?”

“If there were, I would like to drink wine from those grapes,” said Dan’l. They were silent for a while and Webster took a flask out and had a long pull.

I leaned against the railing and patted my own flask, although the sun was yet not high enough to play upon the stream. “And, they say a sea serpent fell in love with you.”

This time it was Dan’l who laughed, and I know it because he doubled over and slapped his knee, tears ran down his face, and he almost dropped his port. “Samanthy, oh, dear boy, what tales do they tell up here in the Old North Woods?”

The boy smiled, and Dan’l cast upstream of the hover, a three-fly rig that drifted down to the bridge so that I got to see every fin twitch and ponder. One fish darted out and took the lead fly, and Dan’l swiftly had it to hand. He squatted by the stream and held it in the water. “Sometimes, you hook them and hold them, and it’s enough. I’m not hungry anymore.”

“Ayuh,” said the boy, a stem of grass dangling from his mouth.

Dan’l nodded, “I was born right over there. If the trees weren’t leafed out you could see it. A mean little cabin, not enough room to turn a horse around in.”

“So they do say.”

Dan’l let the fish go. “I thought I was coming to visit home, but I cannot seem to pass the stream by.”

The breeze that sought the warm air from the cool forest died down. You could hear the clicking of the grasshoppers, the conk-la-ree! call of red-winged blackbirds, and the chickadees going fee-bee! Somewhere on the edge of a field up by the farmhouse around the bend, you could hear a pileated woodpecker pounding out his territorial decree. A horsefly wended its way down the stream, lifted off of the water just to buzz me, and went on its way. The horse tore at the grass. Dan’l fiddled needlessly with his fly rig, and lifting it high, dappled it into slack water where he could ignore it for a time.

“Do you think it works like that?”

Dan’l jerked out of reverie. “Pardon?”

“Do you think, it’s all weighed on your weakest moment? Like you fell off the edge of a knife. Hell would be a busy place.”

Dan’l stroked his chin. “When I was young, I thought to change the world. There’s some say I did.” He looked over at the boy. “There’s others who will say that when I tried to get the power to make those changes, I gave up the very things I fought for.”

“So they weighs the things you did against the things you didn’t? That seems mighty complicated.”

“It’s a calculus, for sure. And I’m afraid, and one that can be very fine in the figuring. It’s hard to say where you land.”

“They say you did save the Union.”

“They also say, you should cut a cancer out, because someday the poison will overwhelm the body. Sometimes, it infects the doctor.”

The boy whistled. Then he smiled. “But you beat the Devil once.”

Dan’l’s flies had drifted ever so slowly out of the eddy and he flicked them back into place.

“Maybe I did save Jabez Stone, but no other. I had sons. They died in wars I could not stop. I had daughters, they did not outlive me. My first wife and my brother Ezekiel, too, are dead. And I have not been …” Another listless flick. “I don’t think you beat the devil, the devil beats you, and beats you, and beats you, until you give in. That’s what I think.” This time when the flies left the pool, he did not mend them, but let them drag in the water, creating a wake like a willow branch. “It’s like trying the same case over and over again. Winning doesn’t matter.”

“A man would get tired.”

Dan’l smiled, from where it came I knew not. His face was gray and haggard, like a week-old bowl of porridge gone cold and dry, but somewhere from its depths a smile came up slowly, the way I once saw a sturgeon, bigger than our boat, rise from the silt of the Kennebec, not there and then there; magnificent, ancient, a force of nature. Dan’l bent his attention to his rod, cast back to the hover, and took another fish, same as the first, the fish just big enough to eat. The fight was short. He offered it up to the boy.

The boy shrugged. “I don’t get so hungry any more, neither.” With a quick opening of the hand, and the slightest toss, Dan’l dismissed the fish back into the stream. “When I was a boy, every fish out of here was the size of my forearm. Well, the size of your forearm.”

“Ayuh. Me too.”

“Two hundred years back?” Daniel took another pull from the flask, then with a grimace, turned it upside down to indicate its vacuity. “I used to say one never gets tired of drink or fishing, but now, neither seem to satisfy.”

The boy stood up and held out his hand. Dan’l held up his rod, “Will I need this?” The boy shook his head. Dan’l put his rod and the flask carefully by the stream and took the hand. When his back was to me, I could see the caked blood matted in his hair and running down his shirt. I was dried to the burgundy of a fine Port. They walked into the cool green forest on the worn granite trail. I watched them until the forest swallowed them, not even a white fin flickering to give them away. When I turned to the grey, he was also gone.

I took a pull from my own flask. The cool morning had segued into the heat of the day. Mosquitos would soon plague me if I stayed here. I walked off the bridge, got in my car and drove the few yards up the street to Daniel’s birth place, where my dad gave talks to the few tourists hungry enough to spare ten minutes out of their lives and pull over by the side of the road to listen to one old man talk about another. He was sitting in the shade of the doorway when I parked and walked up.

“I saw Daniel under the bridge, talking to a small boy.”

“Ah, that explains why he hasn’t been by today,” said my father, shaking the pegs out of the cribbage board. “Catch anything?”

“Nothing of significance. I don’t reckon he’ll be back.”

My father looked at me, “No, I reckon not. Cut?”

Credit: Source link