The key to catching lots of brookies from a mountain stream is to move fast and hit all the right spots.

Photo by Sandy Hays

The keys to catching good numbers of trout on steep mountain streams are stealth and speed. Wild brook trout are wary, fast, and can hide in tiny spaces. There are lots of predators that eat these fish, so they’ve evolved heightened senses and evasive maneuvers. You need to learn how to move and fish upstream without spooking the fish in front of you, and you want to cover as much water as possible to get your fly in front of more fish. Think stealth and speed.

Always work upstream, which gives you the advantage of approaching trout from the rear. Some folks take extreme stealth measures—crawling on hands and knees up to each pool—but if you simply crouch, avoid jerky movements, and keep your shadow off the water, you should be fine. Because you’re working upstream, you can see the series of pools and runs ahead of you. Plan a course upstream that will put you in the best position to cast and avoid throwing your shadow on the water. A good small-stream angler is like a chess player, always thinking several moves ahead.

When you get to the bottom of a pool, your goal is to drop your fly everywhere a trout might be hiding (since you can rarely spot brook trout) and to do this quickly, so you can move on to the next pool. When you look at a pool, there are usually plenty of likely fish lies—under the whitewater at the head, alongside rocks, current seams, and so on. Divide the pool into a grid, and work your way upstream such that each cast leads to the next one. By starting close and planning your casts, you can keep from throwing your line over any likely holding spots before you get a chance to put your fly there.

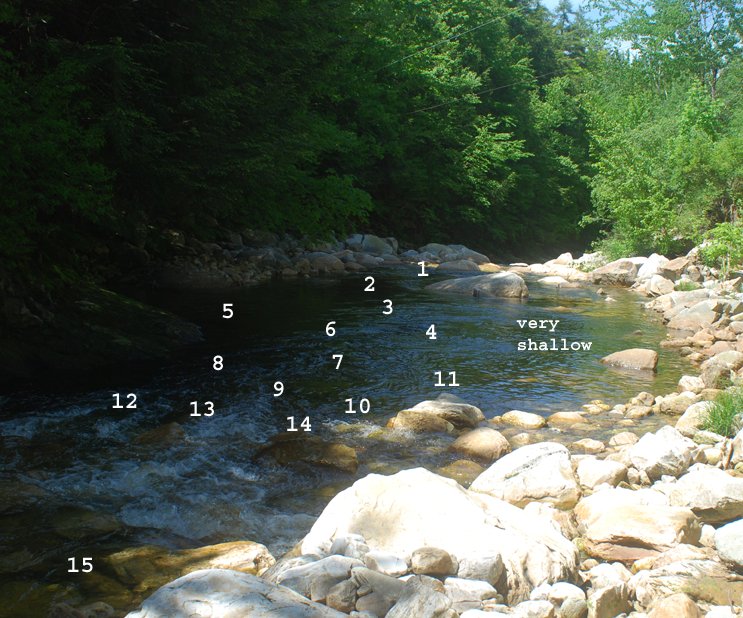

I always work on the assumption that, because food is often scarce in these waters, if a mountain brookie is going to strike, it’ll hit the fly the first time it sees it. So I don’t make multiple casts to the same spot. The accompanying photo of a mountain pool shows a series of casts that would allow you to cover the water quickly. The shot is taken looking downstream. You would approach from downstream, facing the camera. The numbers indicate the order of the casts and where your dry fly should land.

The right sequence of casts allows you to put the fly in the most likely holding spots without spooking any trout. This photo is taken looking downstream; the angler would approach moving upstream (top of the photo).

Photo by Phil Monahan

1. Your first cast should be just above the lip where the pool drains. You’d be surprised how many fish will strike just as your fly is about to go “over the falls” into the whitewater below.

2. The “funnel” where the pool narrows, thus focusing the current and food supply.

3. The near side of the main current seam, allowing the drift to continue around the near side of the midstream rock.

4. The tailout of the main current, allowing the fly to drift into the cushion in front of the rock.

5. The near corner, where slow water meets the main current.

6. The near side of the main current in the middle of the pool.

7. The center of the main current.

8, 9, 10. Working from near to far across the top of the pool.

11. The far corner, where slow water meets the main current.

12, 13, 14. Working from near to far to hit the soft water next to the whitewater.

Cast number 15 hits the lip of the next pool upstream.

Although it takes 14 casts to cover this small pool, these are quick, short casts. You don’t want to put much line of the water in these turbulent currents, and your normal drift will be just a few feet. The 14 casts shown here should take no more than two minutes. (The water on the right in the photo is very shallow, so it probably doesn’t hold trout.)

For this kind of fishing, you’ll want a short rod, which allows you to make quick casts in tight quarters. As much as possible, high-stick your fly through its drift, keeping the fly line off the water. When you’re done with a drift, one or two drying false casts are all that are needed before you drop your fly in the next spot.

Credit: Source link