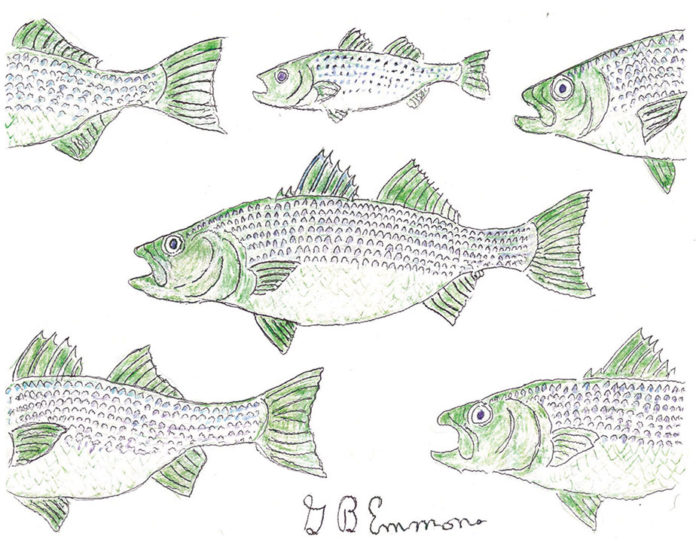

When the family of ospreys moved south in late September, leaving behind the empty nest on a tall pole just behind our seaside terrace on Little Bay in Fairhaven, my wife Jan and I thought our afternoon bird-watching entertainment had come to a close until next Spring. However, the panoramic view there extends for several miles up and down the coastline in both directions for a diverse wildlife observation. And as shorter days and longer nights soon brought a change of activity, the empty void around the shore was soon filled with clamoring flocks of diving gulls and terns to snatch up rising baitfish driven up to the surface of the water to escape schooling striped bass (see illustration).

As a prized trophy-game fish around Buzzards Bay, the striped bass has earned an abridged nickname of “striper” by devoted anglers, many of whom are dedicated fly fishermen and women for this iconic effigy of the sport-fishing mentality.

The striper is named for the seven dark stripe markings that extend all along the upper body from head to tail. Similarly, the popular brook trout has been dubbed “a brookie” by freshwater followers. And because the striper is frequently taken close to shore of their preferred habitat, rocky jetties, and breakwater peninsulas, it is often considered a rock bass. Along the reaches of autumn migration south, it is a route below the water of the Atlantic flyway of the ospreys, following their seasonal retreat.

There are three major striper areas that make up for the migration, either coming or going in season: Cape Ann Bay, Cape Cod Bay, and Nantucket Sound. Moving through a funnel of activity, the Cape Cod Canal serves as the landscape aorta of aquatic circulation of stripers, often lining up bait-, fly- and spin-casting hopefuls all along its reaches. Some are able to cast almost the full width to the other shore, and local fishing publications often outline accepted etiquette manners for participants to avoid tangling lines.

Sportsmanship is the byword of the striper world, as is conservation to preserve the species to recover from commercial over-fishing of the year 1970 with strict regulations to keep only one fish, more than 28 inches or more than 35 inches. These ranges of size give smaller ones a chance to grow bigger and larger ones, often females, the opportunity to annually lay a half-million eggs.

State and federal tagging programs have revealed that, after migrating south from here, they head for the mouth of the Hudson, Connecticut, or Delaware rivers, as far as the Chesapeake Bay.

They are anadromous, meaning they are looking to return to their natal river source to spawn in freshwater. This phenomenon is also practiced by herring, shad, and salmon. How they are able to find the very ideal location, often where they themselves were spawned, is a matter we researched with Dartmouth College when I was active with the Berkshire Hatchery for the Connecticut salmon restoration program. We began by correcting the identification failures by imprinting the fingerlings to be stocked with fluids of amino acids of the Connecticut River itself so that, when they later in life migrated down from Newfoundland past the outgoing current, they would recognize it as coming from their mother pools and turn in to follow their lead to the source.

On Little Bay, as water temperatures dropped below 60 degrees, we marvel that cold nights also painted the deciduous forest with brilliant shades of autumn, and schools of striped bass are following the ospreys in migration. They are moving by as falling leaves fly by our seaward windows, toward the spawning location of their own reincarnation as orchestrated by the planets in the heavens.

Credit: Source link