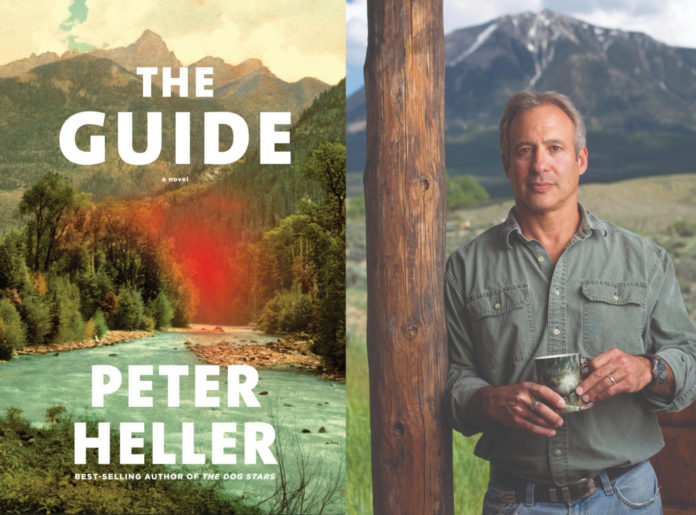

Even when Peter Heller was an award-winning adventure and outdoors journalist he aspired to be a novelist.

“I’d been thinking of myself as a fiction writer since I was 11 and journalism was a way to make a living,” he says. “I used magazine writing as a training ground, using my chops as a poet and developing characters that jumped off the page – even when I was writing for Business Week about fracking I’d write as lyrically as I could, starting the story knee-deep in a creek, fly fishing.”

The protagonist of Heller’s latest novelist, “The Guide,” spends much of the book knee-deep in water, fly fishing, too. But he must also navigate a recurring and mutating virus (the book was written before the Delta variant emerged) and the way it warps society in unforeseen ways.

Heller’s first novel, “The Dog Stars,” was a well-reviewed best seller with a post-apocalyptic setting. “I just started with the first line, it had a cadence I liked and l let the music of the language carry me into the story,” Heller recalls. “It wasn’t until page three that I realized it was a post-apocalyptic novel. I wanted to write literary fiction, not genre, but the voice was so compelling I just wrote it.”

While he does exert authorial control at some points, especially in revisions, Heller says the key to his writing is “telling myself, ‘Don’t think, just listen.’ Mostly, I let the language carry me, I come around the bend in the narrative and I don’t know what’s there. I want to be as thrilled as the reader.”

Each book has carried him on very different routes: “The Painter” was about a talented but troubled artist, “Celine” focused on a hypercompetent aristocratic private eye, and “The River” followed two college-age young men on a canoe trip that crackles with danger from the environment and from people. But for the first time, Heller is returning to semi-familiar ground – Jack is now thousands of miles from that canoe trip but he is again in peril as the main character of “The Guide,” in which the rich find new ways to insulate themselves from the rest of society.

Heller spoke by Zoom about what drew him back to Jack, what role his wife has played in his work and how he reconciles the worst of human nature with the beauty he sees every day.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Q. Why return to Jack?

Jack lives in my heart like an old dear friend I’ve known my whole life, so I wanted to check in and see how he’s doing. It’s kind of crazy and so beautiful to think that way.

Some of my characters are portraits of people I know; Jim Stegner in “The Painter” is Jim Wagner, a friend and a real artist in Taos. I had to ask him if it was okay—he loved the book, but it was so real to him that he said, ‘I’m wandering around the house wondering if I killed a guy.’

But some characters are doppelgangers for me – they love the things I love and have aversions to the same things. I really relate to Jack. He’s a lot like me, his wariness of people, his passions and loyalty are a lot like mine.

I just finished another novel that’s not about Jack, but I’m about to start the next one – maybe I’ll check in on him again to see what he’s up to.

Q. Jack’s friendship with Wynn, which is at the heart of “The River,” is based on a real one of yours.

That book has two origin stories. That scene where the two boys are hiking in the mountains on their college orientation and getting way out ahead of everyone? That really happened freshmen year for me, and he’s still one of my dearest friends.

But the river and canoe trip comes from something that happened with my now-wife. On our third date, she had to drop her gym bag off first. It was really heavy and I looked and there were daggers and throwing stars in there: She was training to be a ninja. She seemed pretty tough, like she could protect me, and I had this assignment to canoe the Winisk River in Canada, which is the real version of the river in the book. So I invited her, but it turns out she’d never been camping or canoeing – and this is deep wilderness.

As we’re packing up, she said, ‘Can I bring my eyebrow tweezers?’ I said no. I should have been more generous – they only weigh a gram. She got me back. It turns out she loves fossils and as we’re going into these whitewaters, she’s loading the boat with more and more rocks of limestone shale with lots of shells in it. The boat is getting low in the water. One morning she had a 12-pound chunk of limestone with a tiny little clamshell in one corner. I said, “Kim.” She narrowed her eyes and said, “Don’t minimize me,” and that’s when I knew I was going to marry her.

Q. Your books feature extraordinary nature writing yet are tense thrillers. How do you find the balance?

My wife takes care of that. I read her chunks of the stuff out loud and I’ll see her nodding off at the end of the couch. I hear this murmur, “Too much fishing,” and I’ll cut it in half.

But also, you can feel where you can get away with a lull, and you can explore the shore of the lake and an eagle hunting, there’s a literary sense of timing and then I can feel when I need to pick it up and make it taut again.

Q. Jack often survives because he believes the worst in people. Is that your worldview?

When I’m in a situation, I am more like Jack than Wynn.

And I sort of feel human beings are a little bit of a mistake. What we’re doing to the planet is more than a crime – I think it’s a sin.

Climate change informs almost all my books in some way. It hurts that tens of thousands of species have already gone into the dark. It’s not as if the apocalypse is coming – for those species it has already happened. We are wreaking evil on the planet. I believe in evil. Evil like the Holocaust and Rwanda are inside us.

Yet so is T.S. Eliot and the poetry of the Tang Dynasty and the acts of kindness we witness every day.

Q. This book is also about wealth and privilege and the abuse of power, which feels very relevant.

Everything going on inside me is going to be expressed and I’ve been thinking a lot about the hollowing out of the middle class and how the wealthy exploit people – it happens with individuals but on an international scale too, with wealthy countries exploiting poor countries. It feels like we’re heading toward “The Hunger Games.” It’s really freaking scary.

Q. But your books aren’t dogmatic or angry.

When I’m writing, I’m in love. And I’m not a despairing person – I find a ton of joy every day and it’s usually connected to nature. If we’re going to have any chance of doing anything worthwhile, we must be resilient, and to do that you have to have fun and take care of each other. In my writing, I find joy and I want to take care of the reader in a certain sense. That’s the only way to tackle the hardest subjects.

Credit: Source link