Chris Smith

It’s late summer in northern Michigan, and for trout fisherman, these are the best of times and the worst of times. Many rivers are off limits from the end of September to the magical opening day in late April, when we’re free to unleash months of pent-up, fly-casting fury on our hallowed waters. May and June are jam-packed with insect hatches — Hendricksons and sulfurs, blue-winged olives and Isonychias, brown drakes and Hexes. The menu is full.

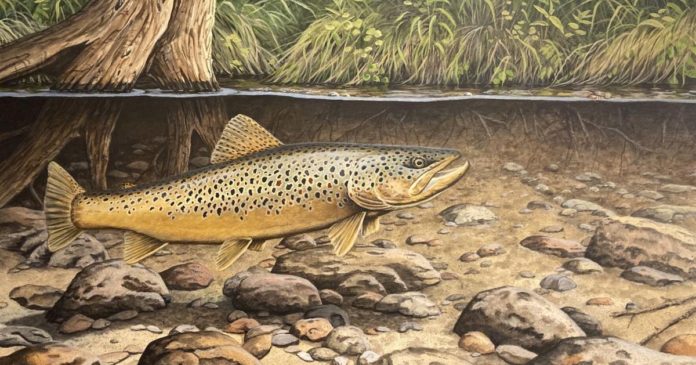

But so is life, with work, family, and vacations competing for every last minute. By the time we look up from the last graduation party or end-of-the-year sporting event, it’s August! Thankfully, trout still need to eat, and the fishing can be just as good, or even better, though admittedly trickier. Much like an opening day buck or gobbler isn’t the educated critter he’ll be two months later, late-summer trout have seen enough pairs of waders, or even felt the hand of man, to become at least cautious. With a little knowledge and consideration, though, there’s still plenty of prime trout fishing to be had.

Most folks greet their favorite stream this time of year with only a handful of patterns that resemble the insects available along the river — grasshoppers, ants, beetles, etc., known collectively as “terrestrials.” Heaving a Hex-sized hopper toward a grassy bank and intentionally plopping it to make some commotion isn’t too tall a task, especially at 2 p.m. on a sunny, breezy August afternoon. Or if you’re lucky enough to catch a flying ant hatch, when anything smallish and black that floats will suffice. But what about “all” the other times, when conditions seem ideal yet nary a trout comes out to play?

After scratching my head long enough, I seek help, and when it comes to late-summer trout, few understand the game as well as Dave Leonhard of Streamside Orvis in Traverse City. When consulted, his initial words were empathetic, for this has been a tough year to catch trout, especially on fickle rivers like the Boardman.

Dave was quick to point out the important role that water temperature plays as summer heat sets in. Stream temps dictate when and where to spend our precious time — accessing stream temp websites surely helps. Anything above the mid-to-upper 60s means fish are searching for cooler, oxygenated bottom waters, or where colder feeder creeks empty into the main stem. Overnight air temperatures in the 50s to low 60s and mid-day temperatures in the 70s and 80s are pretty optimal.

Given these “normal” summer conditions, Dave suggests three proven tactics for summer trout: early morning, mid-day, and evening hatches, but also emphasized a fourth type — nighttime mousing — when extra warm temps slow down the other types of fishing.

Early morning finds big browns still cruising from the night, and streamer patterns can be productive for these predatory fish. Before first light to 7 a.m. is an effective time, which coincides with our longest-lasting hatch, the Trico. Put your cheaters on, though, because these flies are small (size 20-26), and tippet is typically 7x. Detecting hits is difficult, so running two flies in tandem, or alongside an attractor pattern, helps. But if Tricos aren’t working, big streamers are never a bad bet.

Midday terrestrial fishing is the go-to for most folks during this time of year. A myriad of hopper patterns can yield hits, but Dave insisted it’s important to know what types of terrestrials to use in certain locations. For instance, a grassy bank should yield grasshoppers, while a shaded stretch of overhanging cedars would mean beetles. A sandy slip slope after a light rain means that congregating ants might be spilling in the river.

Evening anglers look to employ any combination of streamers, stimulators (stone-flies), or Isonychias, and are always on the lookout for the Ephoron, or “white” mayflies that show up now and then and can blanket the water like Hex.

Mousing offers a final option, which is the ultimate “hit and miss” for big browns after dark. According to Dave, new moon nights are much more preferable, as is warm weather that keeps fish inactive during the day and more willing to feed at night. Given these conditions, he searches for dark pools, preferably in slower-moving water so flies are clearly visible to fish. From there, it’s pretty simple: simulate a mouse subtly swimming toward shore.

This is patient, stealthy fishing, typically without a regular rising fish, but if executed properly, it’s tough for any big trout in the vicinity to pass up. To tilt the odds in your favor, Dave suggests a couple of tips: slightly skitter the fly to imitate a wet mouse scrambling to the bank; and when a strike occurs, be slow(er) to set the hook, or, like some guides will recommend to their clients, say “God save the queen” before lifting the rod. Strangely, a big trout sometimes whacks a mouse, perhaps to stun it, without biting it at first, often returning quickly to actually eat it. If you lift the rod tip or pull back to set the hook on that initial hit, you’ll usually miss, not to mention wrapping the fly in the alders behind you. It’s best to hesitate at that first strike, leaving the fly on the water until you feel tension, then strip-setting if possible, or at least lightly lifting up until feeling a fish on, then setting the hook. This all unfolds in two seconds of horrific, pitch-dark panic, so easier said than done. But when it happens … oh my.

Late-summer offers some difficult but rewarding fishing. The waters are warm, so leave the waders hanging in the shed, grab an old pair of wading boots, a couple of boxes filled with everything from a No. 24 Tricos to something the size of a hapster, and hit the drink!

Credit: Source link