Harrisville, Mich. — The author of the bumper sticker maxim that “A Bad Day Fishing is Better than a Good Day Working” never sat on the shore of Lake Huron with Jay Hall during the fall salmon run.

The 47-year-old mechanic from Flint was perched on a collapsible chair on a windless fall day, hands stuffed in his jacket pockets, fishing pole propped in the crotch of a twig stuck in lakeshore muck. His gear would have been dragged out to sea had a salmon hit, but Hall wasn’t much worried about that. He was at the end of a bad fishing trip, one that had yielded not a nibble.

“It’s just — it’s just depressing,” he said in a voice as flat as the glassy harbor. “Man it is.”

To grasp the depth of Hall’s disappointment, you have to understand where he was coming from: Fall, 1989, the last time he went salmon fishing along the shoreline in Harrisville.

Like so many of eastern Michigan’s coastal towns back then, Harrisville swarmed each fall with shoreline anglers plucking chinook out of the lake with such regularity it was as if they were coming off a General Motors assembly line. Reeling in “king” salmon back then was blue-collar sport — all you needed was a pole and patch of public shoreline.

Hall remembered the carnival of the harbor parking lot. Beer flowed; car radios blared. But what he recalled most vividly was the crisp fall air tinged with the scent of burning hardwood from a nearby salmon smokehouse. And the old guy who filleted mounds of bronze carcasses for a dollar apiece — slicing and slinging fish skins into garbage cans with what seemed to be one fluid motion.

Hall and a friend rolled home to Flint that 1989 day, arms sore from fighting the 20-pounders, the back seat of their Geo Metro folded down to make space for coolers loaded with pale-orange fillets. Hall moved away soon after and only recently returned to Michigan to care for his aging mother. He figured one upside to landing back in his home state was that he could once again hit Lake Huron’s fall salmon run.

But now that the day had finally come, he didn’t feel any of the old exhilaration. All he felt was foolish. On the drive up from Flint, Hall had worried aloud to his brother-in-law that the shoreline might be too packed to find a good spot. When they arrived, the sprawling boat-launch parking lots were empty. Not a single angler could be found on the shore. Only a lone pontoon boat puttered about the harbor.

The fish fillet station was gone. So was the old bait shop, and the only smoke in the air was from Hall’s sad cigarette exhales.

“This used to be the hot spot,” he kept trying to convince his brother-in-law. “It used to be. It really did!”

After less than two hours they grabbed their gear and headed for the parking lot feeling as hollow as the three coolers in the back of the Dodge minivan.

The lake of Hall’s memory is dead, its salmon all but vanished in the past decade — a collapse so swift that fisheries biologists have likened it to driving off a cliff.

For a brief few decades, those biologists had turned this Great Lake into a Pacific chinook factory, taking a wildly popular sport fish from faraway ocean waters and setting it loose to gorge upon the swarms of invasive alewives that had decimated native fish species. In the end, the salmon program proved to be a leaky bandage on a massive biological hemorrhage — the onslaught of invasive species that have infested the Great Lakes since the St. Lawrence Seaway opened the long-isolated freshwater seas to all manner of ecological contagia from around the globe.

Yet what’s happened on Lake Huron is not just a story about the death of its man-made Pacific salmon fishery.

It’s also about the rise of something nobody expected — Mother Nature herself.

This Great Lake, it turns out, possessed a remarkable ability to heal itself; the salmon and their preferred prey — the alewives — ultimately succumbed to wave after wave of new invasions since the early 1990s. But the lake’s native fish species, built to thrive in its frigid and relatively sterile waters, have figured out how to thrive amid all this fresh ecological chaos by feasting on the new intruders. The questions now:

Will this resurrection of native fish spread across the Great Lakes?

And will it even matter if we fail to close the doors to the next invasion?

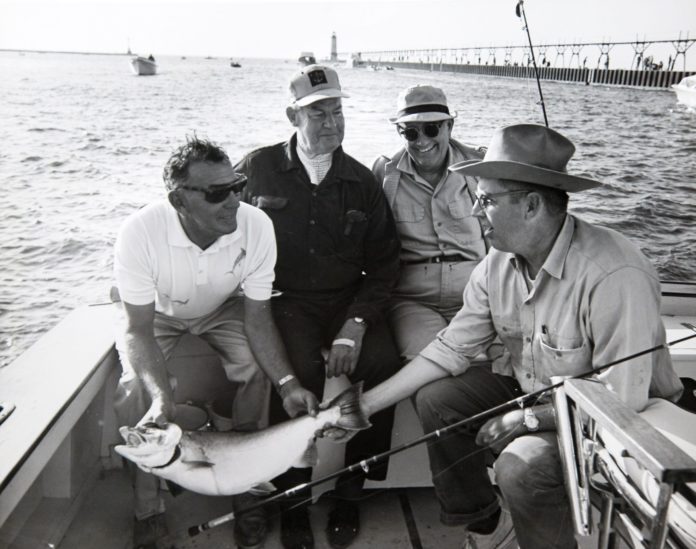

Perhaps no single person has had a bigger impact on the Great Lakes as we know them than Howard Tanner.

Known as “The Father of the Coho,” Dr. Howard Tanner, 91, of Haslett, Michigan reflects on his career and achievements as the former director of…

Known as “The Father of the Coho,” Dr. Howard Tanner, 91, of Haslett, Michigan reflects on his career and achievements as the former director of the Michigan Department of Natural Resources, Wednesday, November 26, 2014, in his Haslett home.

Born on Sept. 4, 1923, the son of a grocer in northern Michigan started fishing on Sunday mornings with his father at age 5. The two chased brook trout near the railroad tracks along the Jordan River in Antrim County — the same region of northwest Michigan fished by a young Ernest Hemingway just several years earlier. Tanner remembers the catch limit at the time was 15 per day, and the Tanners, like everyone else in those days, were not catch-and-release guys. Especially after the country entered the Great Depression, his father lost the store, became sheriff and moved the family into the living quarters of the county jail.

“We ate all we caught,” the 91-year-old Tanner told the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. “There was no question about that.”

By age 15, Tanner had printed up business cards declaring himself a professional fishing guide and was taking wealthy city anglers to inland lakes to chase smallmouth bass, or fly fishing on the Jordan River.

By age 23, Tanner was a World War II veteran who had helped carve airstrips out of the jungles of the South Pacific.

By age 29, Tanner had acquired a doctorate in fisheries biology from Michigan State University.

His first job after graduation was as portentous as it was ambitious. He literally turned life upside down in a little lake in the middle of a Michigan state forest using a generator, a pump and a pipe to suck the water 40 feet up from the bottom to the surface.

“The research reason for that was the nutrients would gradually settle to the bottom of the lake, but there was no oxygen down there for biological activity and the question was: What would happen if you pumped that nutrient-rich water back up on the surface where there was sunlight and life?”

As the junior scientist in the experiment, it was Tanner’s job to maintain the generator that ran around the clock on the shore of West Lost Lake. He still vividly remembers one early summer morning in 1952.

“There was a fisherman sitting on the bank with his rod, smoking a pipe as I put gas in and checked the oil, and I went over to say good morning. He said: ‘Could you tell me what you’re doing?’ And I said: ‘Yes, we’re sucking the water off the bottom of the lake and putting it up on the top.’ He looked at me and said: ‘That’s just exactly what I thought,’ and walked away,” Tanner said with a wry smile. “I can hear him in the bar saying, ‘You know what I saw today?'”

The experiment did what was expected — it sparked a bloom of plankton near the surface. But the flicker of life flared out once the scientists turned off the pump.

“It probably resumed its normal situation in a week or two,” Tanner said, though he did not stick around long enough to find out.

At summer’s end, he headed with his wife and two young sons to Colorado, where he had landed a job at what is now Colorado State University. Since Michigan’s state conservation department paid for his education, Tanner had expected the department would hire him. He was a bit disappointed at the time. But looking back more than a half-century later, he said that move was exactly what was needed for his own professional development — and for the future of the Great Lakes.

He found the Western approach to fishery management “totally different, in almost every way” from how biologists approached the job in the Great Lakes region.

Perhaps the most important distinction is that so many water bodies out West are vast man-made pools created by concrete and earthen dams. This made them blank canvasses for fishery managers to construct an ecosystem almost from scratch.

“When you create new water and there is nothing in it,” said Tanner, “you plant something.”

Hatchery-raised sport fish like trout and bass were planted with abandon, the fish eggs shared in a manner that created bonds between fishery managers and researchers stretching across state lines.

This build-it-yourself approach to fishery management, and the friends Tanner made in top state fishery jobs across the West, proved immensely important not long after a phone call came in 1964 from one of his old professors. He told Tanner that his home state needed a fisheries chief. Tanner’s career was thriving in Colorado, where he had become chief of fisheries research. But there were lures.

His father back in Michigan was battling cancer and his father-in-law also had been ill. The money was better and, perhaps most significantly, there was the vastness of the Great Lakes — the world’s largest freshwater system.

“I immediately began to think about all the water back there,” Tanner said.

Colorado’s largest lake at the time was 7,200-acre Lake Granby — scarcely a puddle on a Great Lakes scale.

“About 50% of the surface freshwater in the 50 states are within the boundaries of Michigan, and the other 49 states shared the rest of it,” Tanner said. “It was a big job.”

And he took it.

The Great Lakes had undergone a devastating ecological transformation in the 12 years Tanner had been gone, particularly Lakes Michigan and Huron. Both had been overrun by alewives, a herring native to the Atlantic Ocean. Like salmon, alewives have a freshwater and saltwater phase in their life cycle. Both species are born in freshwater and then descend to the sea before returning to their native waters to spawn. Typically.

The alewives that had wriggled their way around Niagara Falls via the Welland Canal found life-sustaining zooplankton and baby fish to feast upon in Lakes Michigan and Huron — enough for them serve as surrogate “seas” for their adult lives.

A Watershed Moment: A Lake Reborn

Since the collapse of invasive alewives and the imported salmon that feed on them, Lake Huron has returned to a more natural balance. A look at the invasion-driven changes that have again made lake trout king of the foodchain.

Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

The fish first made it into Lake Huron in the 1930s, but their numbers exploded in the late 1950s in the wake of the demise of the Great Lakes’ native lake trout. Consider lake trout the wolf of the freshwater deep. The beasts atop the food chain could grow to 80 pounds by feasting upon all the smaller fish below — including the newly arrived alewives.

Lake trout might have kept alewife numbers in check. But the king of the lake was toppled by a nearly simultaneous invasion of the Atlantic Ocean sea lamprey, which also slithered into the lakes through the Welland Canal.

These eel-like parasites destroy their prey by swimming up alongside and then latching onto the fish with suction-cup mouths. They use a tongue rough as sandpaper to rasp away their host’s skin and scales, then suck the life out of the fish. One 18-inch-long, bratwurst-thick lamprey can destroy up to 40 pounds of fish during the 12 to 20 months it lives in open waters.

By the time Tanner returned to Michigan in the fall of 1964, decades of commercial overfishing and the lamprey invasion had combined to decimate Huron and Michigan’s lake trout population.

With the disappearance of this top predator, alewife numbers exploded as they outcompeted the lakes’ other smaller fish. Alewives eventually accounted for up to 90% of the fish biomass in Lake Michigan. That means that for every 10 pounds of fish swimming in the lake, nine of those pounds were alewives.

Dominant as they were, alewives did not evolve to withstand the Great Lakes’ wild temperature swings. That led to frequent die-offs by the billions that plugged city drinking water intakes and smothered beaches under reeking mounds of rotting flesh that had to be cleared with bulldozers and dump trucks.

Trying to counter the one-two punch of the alewife and lamprey invasions, Great Lakes biologists seized on a chink in the lamprey life cycle: The parasites don’t reproduce in open waters but spawn in a relatively small number of rivers that feed the lakes.

This allowed researchers to concoct a lamprey-specific poison that was pumped into key rivers and streams. By the time Tanner returned to Michigan in 1964, biologists were dispensing this “lampricide” — essentially an ecosystem-scale chemotherapy — on tributaries across the Great Lakes. The poisoning program, which continues today, ultimately suppressed lamprey numbers to about 10% of their late 1950s’ peak.

Despite the initial decline in lamprey, the alewife infestation was raging when Tanner returned to Michigan because the lakes still lacked enough predators to keep their numbers in check.

On one of his first days on the job, Tanner grasped the scope of the trouble he had inherited. He was touring northern Lake Michigan in an airplane west of Beaver Island. There was a massive white blob on the water, which the pilot identified as one of the lake’s dead alewife slicks. Tanner asked the pilot to bank the twin-engine plane so he could get a closer look. Amazed by the scale of the alabaster blotch floating upon the vast blue sea, Tanner asked the pilot how big of a mess of alewives he was looking at.

The pilot told him it was about seven miles long and two-thirds of a mile across. The surface area of this single slick of dead alewives was nearly the size of Tanner’s largest lake in Colorado.

“That was the first eyeball experience I had,” said Tanner, who has written a soon-to-be-published book on the history of Great Lakes salmon.

“That was a very, very impressive sight.”

While most considered the alewife explosion a natural disaster, Tanner assessed it as an opportunity. His boss, after all, had given him one primary directive:

“The fish division hasn’t done anything new in 20 years. Get out there and do something big and spectacular.”

The natural choice for a top predator after the lampreys were thinned was the native lake trout, small populations of which continued to hang on in parts of Lake Superior and northern Lake Huron.

The torpedo-shaped trout can grow as long as three feet and take the better part of a century doing it. This is important, because the cold waters of the upper Great Lakes were historically prone to booms and busts in prey fish populations. This is not a problem for slow-growing lake trout, which are able to throttle down their metabolism in tough times and wait it out until another bumper crop of little fish arrives.

What is a problem for lake trout is that they were never hugely popular with sport fishermen on the deep waters of the Great Lakes. This is because some strains of lake trout can become something of a dead weight on the end of a fishing line if they are hooked in deep water.

It’s not for lack of heart, but an inability to quickly expel the air in a swim bladder that allows them to adjust buoyancy so they can swim at greatly varying depths. The rapid loss of pressure as one is reeled from the deep can inflate that bladder to the point that some fish pop to the surface after mustering a relatively feeble fight for such a large fish.

Licensed to manage with audacity, Tanner thought a better option for the Great Lakes would be Pacific salmon, tailor-made to feast on species like the alewife — prey fish that swim by the thousands in massive schools high up in the water column.

Salmon feed with such ferocity that they can grow to 40 pounds during their three-year life cycle. It can take a lumbering lake trout 40 or 50 years to reach that weight, carrying much of it as belly fat.

Pacific salmon, on the other hand, are essentially swimming muscles that can chase their prey for thousands of miles before fighting hundreds of miles upstream against tumbling mountain rivers to spawn and die. Salmon also can burp out their swim bladder gas to allow them to take their fight against a fisherman all the way to the deck of a boat, as Tanner had thrillingly learned firsthand from an earlier fishing trip on the Pacific Ocean.

Tanner’s goal wasn’t to just alter the species composition of the lakes; he wanted to change the public’s relationship with the lakes themselves. Beyond pier fishing for perch and smallmouth bass, fishing in the lakes primarily had been the domain of relatively few commercial fishing crews using big boats and nets to harvest lake trout, perch, whitefish and chubs for restaurants and stores.

But because these commercially fished native species had been so destroyed by overfishing and the lamprey and alewife infestations, Tanner inherited something of a blank slate — almost like a freshly filled reservoir in the West. He had little interest in trying to repaint the same old picture, but wanted instead to turn the waters over to large numbers of sportsmen who fished as much for thrill as fillet.

“You manage the resource to produce the greatest good for the greatest number for the longest period of time,” Tanner said, borrowing the axiom of the first boss of the U.S. Forest Service, Gifford Pinchot, a champion of squeezing as much economic benefit from the nation’s public forests as was sustainable.

“And for a century, probably, commercial fishing fit that criteria,” Tanner said. “But in 1964 it was long past.”

There had been dozens of earlier attempts to plant salmon in the lakes dating back to the 1870s. All had flickered and failed, save for one tiny population in Lake Superior. The previous stocking programs failed because they were not sustained year after year, or included salmon species ill-suited for the waters of the Great Lakes, or because the stocking was done in the wrong place or at the wrong time of salmon’s life cycle.

But, most importantly, those stocking experiments happened before the lakes were bursting with alewives.

Tanner thought there was a chance Pacific salmon, like alewives, would reproduce on their own once they got a foothold in the Great Lakes. But he was not banking on it and was prepared to embark on an annual stocking program that could last years, decades, even longer.

He just did not know how to get it started. Tanner had tried for years back in Colorado to acquire coho salmon eggs from colleagues in the Pacific Northwest to plant in Rocky Mountain reservoirs. For years he had been rebuffed.

The northwest hatchery workers, trying to bolster wild stocks ravaged by dams that plugged migration routes to the sea, were having a hard time figuring out how to keep hatchery salmon fed. Hatchery workers had to grind things like salmon eggs, liver and spleens each day to feed the baby fish. It was a work-intensive, hit-or-miss process that brought too-little success in raising fish that could actually survive a trip to the ocean — and back to where they were planted.

But the emergence in the early 1960s of a vitamin-dosed, pasteurized fish pellet made of things like wheat germ and herring guts suddenly changed that. It could be whipped up in industrial-size batches and dispensed daily. It led to a boom in raising salmon out West and that, eventually, led to a phone call Tanner got barely six weeks after he took the Michigan job. An old colleague said Oregon might have some coho eggs to share, a salmon species similar to chinook, though smaller.

“I didn’t believe it,” Tanner said. “I’m thinking if that was true, then the opportunity was there. It was — it just was crystal clear. I mean, everything would fit. There would be a food supply. The waters were suitable in temperature. … And if I chose to do it, we could do it.”

Tanner made a call to Oregon the next day and found biologists really did have salmon eggs to share, due largely to the newly concocted fish food.

He went to his bosses at the Michigan Department of Conservation and got their approval almost immediately. In December 1964 — less than four months after he took the job — the first batch of an initial gift from Oregon of 1 million coho eggs was loaded on a plane bound for Michigan.

Tanner’s push to plant in Michigan waters an exotic fish that could, theoretically, roam from one end of the Great Lakes to the other had obvious ramifications for the other Great Lakes states of Wisconsin, Minnesota, Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania and New York as well as the Province of Ontario. The U.S. government, meanwhile, had its own plan to restore native lake trout to help revive the lakes’ commercial fishing industry.

But once Tanner got approval from the board overseeing the Michigan conservation department, he and his superiors acted alone — with a focus and purposefulness that reflected their collective war experiences.

Tanner had helped carve airstrips from jungles as a member of the Army’s Signal Corps. His boss had led Marines ashore. And that guy’s boss had been a bomber pilot over Germany.

“If something needed to be done, you did it,” Tanner said of the battle-hardened group.

Coho would be just the first wave of plantings, an enterprise Tanner and his colleagues referred to as “farming” the Great Lakes to create an unmatched recreational fishery.

“The ultimate aim is to convert an estimated annual production of 200 million pounds of low-value fishes — mainly alewives — that now teem in the upper Great Lakes into an abundance of sport fishes for recreational fishermen,” Tanner and his assistant Wayne Tody wrote in a 1966 report issued just two months before the first salmon crop was planted in Lake Michigan.

Just like the experiment on West Lost Lake 14 years earlier, Tanner again set out to turn life upside down in a lake. But now the scope of his ambitions had reached a Great Lakes scale.

“All my life I have marveled that one person, that happened to be me, was given the opportunity and the authority to make a decision of this magnitude,” he said.

On a snowy April 2, 1966, Tanner, wearing a tie and overcoat, took a microphone on a makeshift stage on the banks of the Platte River flowing into Lake Michigan southwest of Traverse City. Dignitaries sat on card table chairs behind him for a brief ceremony before a state legislator picked up a ceremonial golden bucket and dumped a load of finger-sized cohos into the river.

Later that day, Tanner tipped his own bucket of coho into a nearby creek — one of the very creeks where Hemingway had fished for trout a half-century earlier. It was a bittersweet moment; Tanner had already quietly agreed to take a new job as a professor at Michigan State University.

“I stood at the banks of Bear Creek and the truck left and the photographers left and I stood there in the snow watching those fish go down to the main stream wondering — how soon and how big?”

Would the fish survive to adulthood, and if so would they return to the river and stream in which they were planted? Would they, as some scoffed, swim east instead for the salty allure of the Atlantic Ocean? Would they just become fish food?

Or would they alter life in the Great Lakes in a manner no one could predict?

Tanner took his worries home and confessed them to his wife as they sipped cocktails.

“I remember telling her, I’m going to be either a hero or a bum,” he said. “Whichever it is, it’s going to be loud and clear. And it’s going to reverberate for a long time.”

Credit: Source link