The iconic species of our oldest national park, the Yellowstone cutthroat draws anglers from around the world.

Photo by USFWS

The names of many legendary fishing spots in Yellowstone National Park—Buffalo Ford, the Lamar Valley, the meadows of Slough Creek—are synonymous with big, native Yellowstone cutthroat trout (Oncorhynchus clarkii bouvieri) that will rise to a dry fly on a summer day. Anglers dream of such places because they combine much of what we love about the sport: that it takes us to where we can experience true wilderness and natural beauty and that it allows us to match wits with a game fish on its home turf, in the very waters where it evolved over tens of thousands of years. In truth, Yellowstone cutthroats are neither the wariest nor the hardest-fighting trout in the West, but they are beautiful, willingly eat flies of all kinds, and inhabit crystal-clear streams in the midst of some incredible landscapes. The YCT is also one of the four subspecies of cutthroats that make up the Wyoming Cutt-Slam, the Utah Cutthroat Slam, and the Nevada Native Fish Slam programs. They’re also part of the Western Native Trout Challenge.

Range and Species History

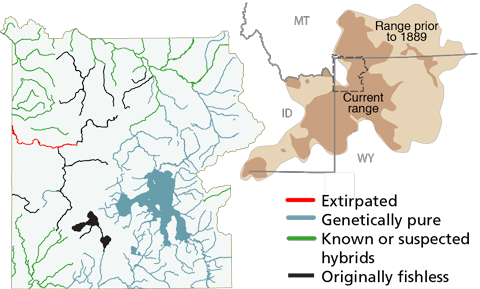

The original range of the Yellowstone Cutthroat Trout (YCT) includes the Yellowstone River drainage upstream of the Tongue River, the Snake River drainage upstream of Shoshone Falls. This includes sizeable swaths of southern Montana, northwestern Wyoming, southeaster Idaho, and extends just a bit into northern Utah and Nevada, as well. The introduction of nonnative trout species—resulting in increased competition and hybridization—and loss of habitat through development and fragmentation have reduced the number of river miles inhabited by YCT to less than 45 percent of historic norms (from approximately 17,400 river miles to just 7,500). Hatcheries in Montana, Wyoming, and Idaho raise YCT to supplement wild stocks and to reintroduce the subspecies to waters where it has been extirpated.

Map via NPS.gov

Yellowstone cutthroats demonstrate three life-history patterns: resident, fluvial, and adfluvial. Resident fish spend their entire lives in on stretch of a stream, usually in headwater streams and those that have been isolated. Fluvial YCT spend most of their lives in the main stem of a river but migrate up tributaries to spawn, and adfluvial fish live in lakes and move to tributaries or outlet streams to spawn. These fluvial and adfluvial populations are most at risk from habitat fragmentation, in which the spawning waters are cut off by roads, culverts, and other obstacles.

YCT prefer cold, clear, oxygenated water with a gravel substrate and little sediment. Good YCT habitat also includes complex cover, such as undercut banks and in-stream woody debris. Spawning occurs in spring and early summer, usually after peak runoff, and the emerging fry may begin migrating immediately. At three years old, they are ready to spawn, and YCT can live up to eleven years.

What’s in a Name?

The Yellowstone cutthroat trout was originally given the Latin name Salmo bouvierii, after a U.S Army captain, in 1883. Later, however, taxonomists lumped the YCT and what we now call the westslope cutthroat into a single subspecies, Salmo clarkii lewisii—named for the great explorers Lewis and Clark, whose Corps of Discovery first encountered cutthroat trout on the Missouri River in 1805. Advances in genetics in the 1960s led scientists to split the subspecies into two again, restoring the name bouvieri to the Yellowstone subspecies and coining the term westslope for the other. Then, in 1989, all trout of the Pacific basin were moved out of the Salmo genus and into the Oncorhynchus genus, reflecting a closer relationship to the Pacific salmon.

Lake Trout Invasion

The key to thriving populations of Yellowstone cutthroats in the Yellowstone River drainage is the incredible fecundity of Yellowstone Lake and its many spawning tributaries. So prolific was the habitat that more than 70,000 YCT were counted at the mouth of a single feeder stream, Clear Creek, in 1978 alone. But by 2007, that number had fallen to just 538. Illegal introduction of Lake Trout by amateur “bucket biologists” sometime in the 1980s caused a massive crash in the cutthroat population, which threatened the entire ecosystem that depends on the fish. A single laker can eat 41 cutthroats per year, and because they live in deep water, lake trout are difficult to eradicate. More than 20 years of gill-netting, as well as catch-and-kill regulations, have allowed the cutthroat population to rebound somewhat, with Clear Creek seeing more than 700 fish in 2016, and biologists are feeling hopeful of further recovery.

Conservation Efforts

Spurred by the decline of Yellowstone cutthroat trout across its historical range, many private/public partnerships have formed to protect the YCT that remain and reestablish populations that have disappeared. Ranchers and state and federal agencies regularly team to protect and restore streams damaged by incompatible farming and grazing practices. These projects benefit fish and landowners, as clean water and reduced erosion protect fish and agriculture. Ranchers are key partners in protecting in-stream flow for YCT with water leases, installing and maintaining fish screens that prevent loss of trout to irrigation diversions, and providing fish passage by replacing impassable culverts or installing fish ladders on irrigation diversions. Conservation NGOs and private companies like Orvis are also valued partners, as they can contribute grant funds, educate the public, and many contribute labor to conservation projects.

Climate change is contracting the suitable habitat for Yellowstone cutthroat trout toward higher elevations, which remain the current stronghold for the species. Conservation of YCT in a warming climate requires prioritizing these high-elevation refuges. Keeping streams healthy, with functioning, protected areas of streamside vegetation, is among the activities that will increase the resilience of individual populations. Adequate stream flow is another essential component in promoting resilience to climate change, and partnerships among water users, and public and private contributors will be essential. Removing the threats posed by nonnative fish will provide safe havens, where YCT can live as they did before introduction of brook trout, rainbow trout, and brown trout.

Flies and Tactics

Depending on habitat and food availability, Yellowstone cutthroats can range from a few inches long to well over 20. The IGFA does not award records for each cutthroat subspecies, so there is no official world record for Yellowstones. However, in August 2016, an Idaho woman landed a 28-inch, 8- to 10-pound fish on the South Fork of the Snake River, which probably one of the largest Yellowstones ever recorded.

Yellowstone cutthroats are less pisciverous than other trout species, feeding more on insects and other invertebrates, which makes Yellowstones more likely to eat dry flies. While matching the hatch is always the best tactic, terrestrial patters such as ants, grasshoppers, and beetles work well from late summer through the first frost. A tandem rig featuring a terrestrial or attractor pattern trailing an emerger can be deadly. If the fish won’t come to the surface, try a double-nymph rig or a small streamer, such as a Woolly Bugger or Zuddler.

Matching the hatch isn’t always necessary when you’re chasing YCTs, but they can be choosy at times.

For More In-Depth Information on YCT:

Credit: Source link